Bet On It reader Vanja Månborg knows a lot about rent control in Sweden. If you think Sweden is a country of thoughtful technocrats where government intervention works well, reading his guest post may make you think again. Here’s Vanja:

Sweden has had rent control regulations since 1917 with less than two decades of pause between the First and Second World War. It is also a country that has the world’s oldest statistical data on population (from 1686!) and excellent statistical data on population and housing today. This offers a unique opportunity to look back at history through the lens of data and see what it tells us about the effects of such an extensive period of rent control.

Much has been written about rent control over the years. Proponents argue that it strengthens the rights of tenants so that the landlords cannot drive them out by unreasonable rents while critics argue that it reduces the supply of rental apartments and creates housing shortages. Sweden, like the rest of Europe, experienced a period of rapid urbanization during the 19th century, especially in its second half. There were only three major cities with more than 10 000 inhabitants in 1800 but this number grew to twenty-two by 1900.

While rental houses existed in the large cities (like Gothenburg and Stockholm) prior to the 19th century, they were rare elsewhere. For hundreds of years, owners of land had rented their sheds and stables for farmworkers during the planting and sowing seasons and this was done in a laissez-faire manner. In fact, there was only a single nationwide law that governed rental contracts from 1734 and it regulated two dates during the year when a contract could be terminated or renegotiated (April and October).

Of course, the larger cities had local regulations. These limited the maximum height of buildings and maximum width of streets. Most buildings in the past were made from timber and such regulations were meant to prevent local fires from spreading and destroying the entire city (think of the Great London Fire in 1666 or the Great Chicago Fire in 1871).

Great Britain was perhaps a hundred years ahead of Sweden in its industrialization process and had already experienced some of its negative effects, such as overcrowded apartments and serious health epidemics. By 1848, they introduced the Public Health Act to improve living conditions in the cities and these ideas were picked up and promoted by Swedish intellectuals. It led His Majesty the King to sign off on the first national building code in 1874. It regulated many different aspects of city building, from how the property should be designed to how wide the streets must be. One important regulation was the height of buildings that were limited to five floors.[1] An interesting fact is that the King could grant a special exemption why the sixth floor came to be known as the King’s floor.

Construction in the 19th century was mostly done by private companies and with the advent of the first financial institutions, the ability to finance construction with loans led to a series of building booms. The concept of “speculative construction” was born where housing became a good to invest in and trade, like spices from the East. Coupled with the provisions in the building code, this period saw the growth of the so called “tenement barracks”. The historian Ohlmarks gives us a glimpse of how it was to live in them:

Those who moved in [into the cities] lived in gigantic and bland rental garrisons; large complexes of one- and two room apartments with depressingly closed off, prison-like stone courtyards, surrounded by dirty, yellow walls. Despite everything, however, these overcrowded, gas-lit colossus was an improvement of the standards for the working classes in those times.[2]

By the end of the century, winds of political change had begun to blow. Dissatisfaction permeated the country and many had emigrated. Between 1850 and 1900, the net emigration from Sweden amounted to a fifth of the total population. The Social Democratic Workers’ Party was founded in 1889 and ideas of workers’ rights begun to take hold.

In 1899, His Majesty the King appointed a “Homeowner Committee” to investigate how to increase the rate of construction so that more people could own their homes. The committee’s recommendations were, among other things, to set up a governmental loan policy for construction of housing that came to be known as “homeowner loans.”[3] Architectural historian Eva Eriksson comments on this in her work on the birth of the modern city: “home ownership was obviously seen by many in the establishment as a way to channel the social tension (…) To strengthen the feeling of home and motherland, which should reduce the tendency to emigrate.”[4] Many of the founders of “grassroot” homeowner associations were government officials of what we would today consider a centre-right government.

At the same time, authors like Gustaf af Geijerstam[5] and Martin Koch[6] wrote about the living conditions of workers (which at least in part) prompted the government to conduct the first ever nationwide housing census in 1912. One major goal was to assess the living conditions, not the least the extent of so called “over crowdedness”.

Then came the War.

Resources such as metals and fuels were diverted towards the war effort throughout Europe and construction halted due to inflated costs and high interest rates. At the same time, urbanization continued. Worried that rents would soar and lead to even more dissatisfaction (and no doubt, worried that power would shift even more to the new Socialist Party), the government passed the first ever nationwide rent control law in 1917. It prohibited “unreasonable” increases of rent.

Figure 1 shows that construction by the end of WWI dropped to pre-boom levels of the previous century. The housing censuses for 1912 and 1920 show that average rent prices increased by 33% in the nation (40% in Stockholm and Gothenburg) while the consumer price index increased by 190% during the same period.

Figure 2, however, shows that the share of rental apartments begun to decline at this point in history.

In 1933, another investigation was launched to “investigate the extent and status of slums in cities and urban centres and steps that could be taken to resolve the poor living conditions.”[7] Their results came 17 years later in a 500+ page report. Sweden should continue the policy of subsides for construction of single-family houses (the “homeowner loans” mentioned earlier) and construction of multi-family houses should be left to companies “without specific profit motives”, under the supervision of the municipalities.

Then the war came again. In 1942, a new rent control law was introduced. It seemed like a repeat of what had happened twenty-five years earlier, except the law was expanded with a maximum rent limit as well as even stronger protections for tenants. The subsidized loan program was expanded as well, with “addition loans” that were meant to cover the additional war-time costs of construction. The number of apartments built with loan subsidies was only 5% in 1939 but increased to almost 100% in 1942.[8]

Figure 3 shows the effect on production of new apartments before and after World War II. Even though production returned to 1930s levels, demand continued to surpass supply until another governmental investigation was launched in 1959 to deal with the housing problem once and for all. It led to what is today known in Sweden as the “Million program”, where the goal was to build a million apartments in ten years. Note, however, that the trend of lower shares of rental apartments (Figure 2) continued almost uninterrupted during this period.

This brings us to the roots of more recent history. The new value-based rent law was introduced in 1969 and was modified in 1978 to allow for a special “negotiation clause”. It allowed the landlord to negotiate general rent increases with tenants instead and was seen as a softer version of rent control (some even claim today that Sweden doesn’t have rent control). In practice, the negotiations are done on a national level between the Tenants’ Union and the Landlord Association. Any disagreements are to be resolved by the housing court that would look at rent levels for similar apartments in similar locations.

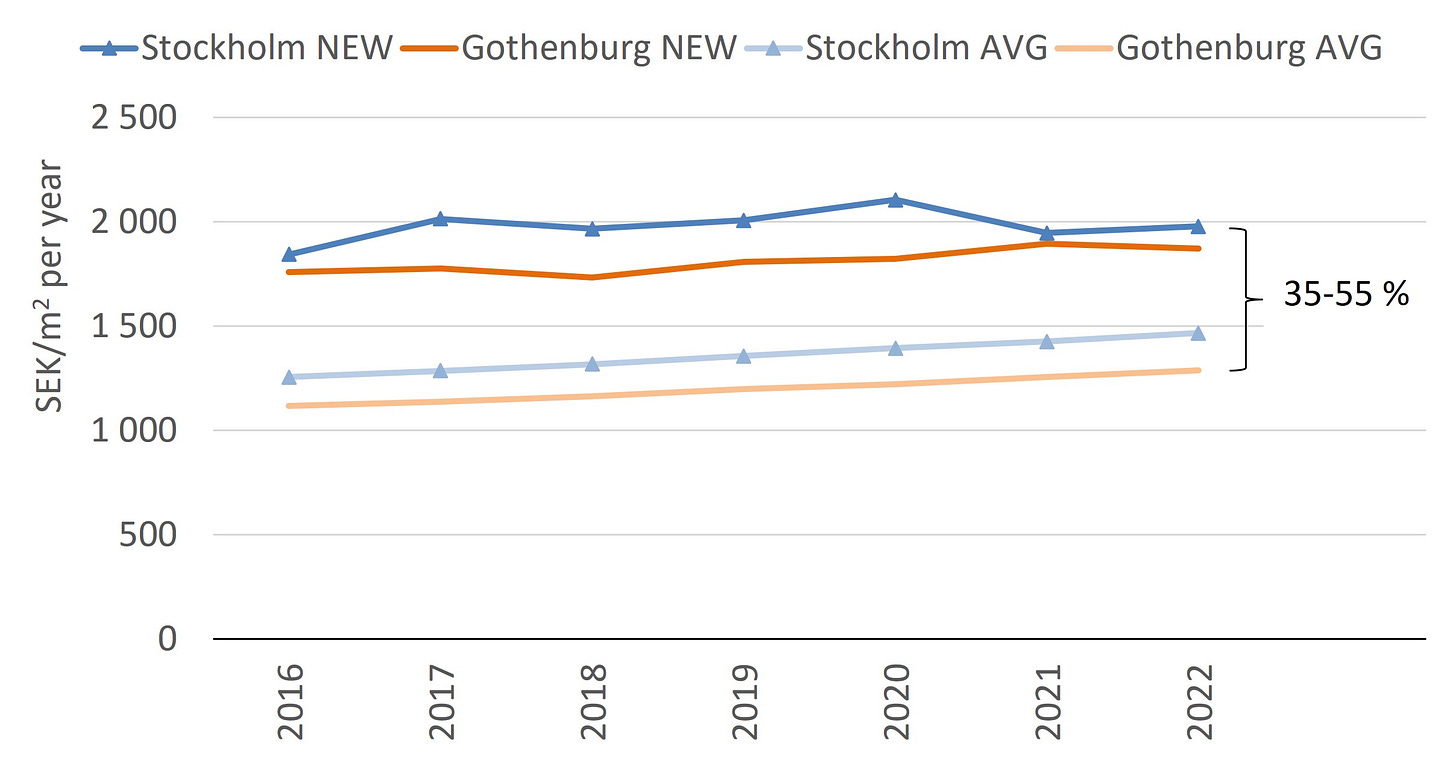

In 2006, the law was again amended to allow rent for newly built apartments to be exempt from the value-based system for fifteen years, after which the value-based system would begin to apply. Figure 4 shows how the rent levels differ between new and average rental apartments from 2016-2022.

The status of the housing market today is that:

- 93% of swedes live in municipalities with a housing shortage,

- the share of rental apartments is on a continuous decline (in Stockholm it went from 54% to 36% in the last 30 years),

- there are long waiting times for first-hand contracts,

- there is a substantial black market and

- compared to the condominium market, the rental market is more segregated.[9]

In conclusion, I would say that the data tells us two stories. One is a warning lesson. Even after 70 years of continuous rent control in various forms, the rental housing market in Sweden seems to be a big mess.

The other story is more one of success. There was a housing shortage after the First World War but it took the market less than a decade to recover. The housing census of 1933 shows that the vacancy numbers had returned to normal levels (2-3%) for a balanced housing market. Perhaps it’s time for Sweden and the rest of the world to try it again?

[1] It should be noted that the first “skyscraper”, the Home Insurance Building, opened around the same time in 1885 in Chicago.

[2] Ohlmarks Å, Baehrendtz N. E. Svensk Kulturhistoria. Stockholm: Forum; 1999: 323-330.

[3] The value of a home was limited to 3000 SEK and the interest set to 3,6%

[4] Eriksson E. Den moderna stadens födelse. Stockholm: Ordfronts förlag; 1990: 348.

[5] Geijerstam G. Anteckningar om arbetarnas bostadsförhållanden i Stockholm. Stockholm: Samson & Wallin; 1894.

[6] Koch M. Arbetare: en historia om hat. Stockholm: Bonniers; 1912.

[7] Bostadssociala utredningen – Del 1. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; SOU 1945:63

[8] Swedish Public Housing Organization, https://www.allmannyttan.se/historia/historiska-epoker/1931-1945-allmannyttans-bostadspolitiska-roll-formas/

[9] Fritzon G. Nio problem med hyresregleringen. Timbro: 2020

>Much has been written about rent control over the years. Proponents argue that it strengthens the rights of tenants so that the landlords cannot drive them out by unreasonable rents while critics argue that it reduces the supply of rental apartments and creates housing shortages

Rent control is theft. Its immoral. End of discussion.

> Of course, the larger cities had local regulations. These limited the maximum height of buildings and maximum width of streets. Most buildings in the past were made from timber and such regulations were meant to prevent local fires from spreading and destroying the entire city

How does a limit on the maximum width of streets help prevent fires from spreading? Wouldn't wider be better?