Several readers have taken issue with my use of the term “ADHD.” To be honest, I’m not comfortable with it either, but my reason is the opposite of my critics. Like the late great Thomas Szasz, my objection is that labels like ADHD medicalize people’s choices – partly to stigmatize, but mostly to excuse. In his words, “The business of psychiatry is to provide society with excuses disguised as diagnoses, and with coercions justified as treatments.” I realize this is an unwelcome view, but I do have a whole paper defending it, and I stand by it.

My general claim:

[A] large fraction of what is called mental illness is nothing other than unusual preferences – fully compatible with basic consumer theory. Alcoholism is the most transparent example: in economic terms, it amounts to an unusually strong preference for alcohol over other goods. But the same holds in numerous other cases. To take a more recent addition to the list of mental disorders, it is natural to conceptualize Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as an exceptionally high disutility of labor, combined with a strong taste for variety.

Consider how economists would respond if anyone other than a mental health professional described a person’s preferences as ‘sick’ or ‘irrational’. Intransitivity aside, the stereotypical economist would quickly point out that these negative adjectives are thinly disguised normative judgments, not scientific or medical claims. Why should mental health professionals be exempt from economists’ standard critique?

This is essentially the question asked by psychiatry’s most vocal internal critic, Thomas Szasz. In his voluminous writings, Szasz has spent over 40 years arguing that mental illness is a ‘myth’ – not in the sense that abnormal behavior does not exist, but rather that ‘diagnosing’ it is an ethical judgment, not a medical one. In a characteristic passage, Szasz (1990: 115) writes that:

Psychiatric diagnoses are stigmatizing labels phrased to resemble medical diagnoses, applied to persons whose behavior annoys or offends others. Those who suffer from and complain of their own behavior are usually classified as ‘neurotic’; those whose behavior makes others suffer, and about whom others complain, are usually classified as ‘psychotic’.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) 1973 vote to take homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses is a microcosm of the overall field (Bayer 1981). The medical science of homosexuality had not changed; there were no new empirical tests that falsified the standard view. Instead, what changed was psychiatrists’ moral judgment of it – or at least their willingness to express negative moral judgments in the face of intensifying gay rights activism. Robert Spitzer, then head of the Nomenclature Committee of the American Psychiatric Association, was especially open about the priority of social acceptance over empirical science. When publicly asked whether he would consider removing fetishism and voyeurism from the psychiatric nomenclature, he responded, ‘I haven’t given much thought to [these problems] and perhaps that is because the voyeurs and the fetishists have not yet organized themselves and forced us to do that’ (Bayer 1981: 190). Even if the consensus view of homosexuality had remained constant, of course, the ‘disease’ label would have remained a covert moral judgment, not a value-free medical diagnosis.

Although Szasz does not use economic language to make his point, this article argues that most of his objections to official notions of mental illness fit comfortably inside the standard economic framework. Indeed, at several points he comes close to reinventing the wheel of consumer choice theory:

We may be dissatisfied with television for two quite different reasons: because the set does not work, or because we dislike the program we are receiving. Similarly, we may be dissatisfied with ourselves for two quite different reasons: because our body does not work (bodily illness), or because we dislike our conduct (mental illness). (Szasz 1990: 127)

My analysis of ADHD specifically:

4.2. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

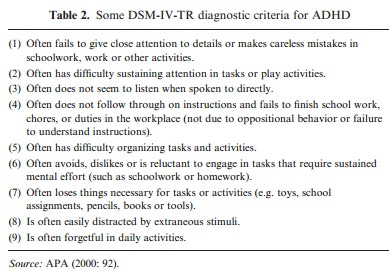

Substance abuse is a particularly straightforward case for economists to analyze, since it involves the trade-off between (1) one’s consumption level of a commodity and (2) the effects of this consumption on other areas of life. But numerous mental disorders have the same structure. One way to be diagnosed with ADHD, for example, is to have six or more of the symptoms of inattention shown in Table 2.

Overall, the most natural way to formalize ADHD in economic terms is as a high disutility of work combined with a strong taste for variety. Undoubtedly, a person who dislikes working will be more likely to fail to ‘finish school work, chores or duties in the workplace’ and be ‘reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort’. Similarly, a person with a strong taste for variety will be ‘easily distracted by extraneous stimuli’ and fail to ‘listen when spoken to directly’, especially since the ignored voices demand attention out of proportion to their entertainment value.

A few of the symptoms of inattention – especially (2), (5) and (9), are worded to sound more like constraints. However, each of these is still probably best interpreted as descriptions of preferences. As the DSM uses the term, a person who ‘has difficulty’ ‘sustaining attention in tasks or play activities’ could just as easily be described as ‘disliking’ sustaining attention. Similarly, while ‘is often forgetful in daily activities’ could be interpreted literally as impaired memory, in context it refers primarily to conveniently forgetting to do things you would rather avoid. No one accuses a boy diagnosed with ADHD of forgetting to play videogames.

What about all the contrary scientific evidence? It’s not really contrary. The best empirics in the world can’t resolve fundamental questions of philosophy of mind.

Another misconception about Szasz is that he denies the connection between physical and mental activity. Critics often cite findings of ‘chemical imbalances’ in the mentally ill. The problem with these claims, from a Szaszian point of view, is not that they find a connection between brain chemistry and behavior. The problem is that ‘imbalance’ is a moral judgment masquerading as a medical one. Supposed we found that nuns had a brain chemistry verifiably different from non-nuns. Would we infer that being a nun is a mental illness?

A closely related misconception is that Szasz ignores medical evidence that many mental illnesses can be effectively treated. Once again, though, the ability of drugs to change brain chemistry and thereby behavior does nothing to show that the initial behavior was ‘sick’. If alcohol makes people less shy, is that evidence that shyness is a disease? An analogous point holds for evidence from behavioral genetics. If homosexuality turns out to be largely or entirely genetic, does that make it a disease?

Bottom line: My use of the term “ADHD” was indeed problematic because the concept itself is problematic. Then why use it? Because you can grasp my original point without sharing my broader perspective – and if I started with my broader perspective, it would drown out my original point.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

"Overall, the most natural way to formalize ADHD in economic terms is as a high disutility of work combined with a strong taste for variety"

How do you formalize autism in economic terms?

I find this maximalist position that all mental illness is fake to be deeply unpersuasive. I think the crux of this debate is over semantics: what does it mean to say someone is unhealthy or ill? I looked back at the original caplan article and this was how "real" illness is defined:

"How can these conditions be formally modeled? Basic consumer theory makes the answer clear: It shifts your budget constraint inwards....Almost every traditional medical condition one can name can be modeled as an inward shift of one or more budget constraints...Budget constraints shift in for many reasons other than disease. But traditional medical conditions and shrunken budget sets go hand in hand."

"Almost every" eh? So what about traditional medical conditions that can't be modeled as an inward shift on budget constraints? Do they not count either? But why should I accept this definition and does any doctor (the "real" kind) model illness this way? A layman's definition of can be roughly summarized:

"An illness is a condition that affects the body or mind, causing dysfunction, discomfort, or distress. It is a state where an individual's physical or mental condition is impaired or below optimal functioning."

Is this definition vague? Yes.

Does it make it hard to clearly identify when someone is sick or not? Yes, it can.

Does culture and ethics heavily influence what we identify as an illness or not? Sure does.

Ethical judgments are inevitable when determining whether someone is sick and what affordances society gives to sick people. Ask an anti-abortionist their opinion on whether abortion is ever medically justified. How about deaf parents who don't want their deaf kids to get hearing aids because it's "killing" the death community?

The "budget constraint" model would be quite puzzling to use in practice. People claim to be sick when "objective" medical diagnostics finds no evidence of sickness. This doesn't mean there's not a problem, it just means there's no neutral third party validation one can do to prove it. Have you ever had a crippling migraine or debilitating chronic pain? How do you prove that you have it? Well, people have to take your word for it.

Do people lie about chronic pain in order to get prescription meds to get high? Sure. Do I believe there are people with horrible chronic pain that are telling the truth? Yes I do. How do you tell the difference? Well, you need to evaluate on a case by case basis.

I see no difference when evaluating mental illnesses. I’ve had personal experience dealing with loved ones who have had severe mental illness. if you ever interacted with someone who has severe clinical depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder then you know “deep in your bones” that something is deeply wrong. This is very much should i believe your too clever by half argument or my lying eyes.