When I wrote Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, “people from larger families ultimately have more kids” was a truism. Almost everyone took it for granted; the only serious controversy was why. Relying on behavioral genetic evidence, I argued that nature once again crushes nurture. The full passage, with endnotes:

Parents have little or no effect on child-bearing. I often half-jokingly tell my three sons that they’re required to have three kids each, but twin studies say I’m wasting my breath. While fertility runs in families, the reason nowadays is almost entirely genetic. A major study of Danish twins born 1870-1910 found moderate nurture effects on family size.[i] Half a century later, though, these nurture effects had disappeared. Upbringing had a tiny influence on when Danes tried to start a family, but none on 35-41-year-olds’ total number of children.[ii] A different team of researchers looked at about 2000 American twins, siblings, half-siblings and cousins born between 1958 and 1965, and found minimal nurture effects on fertility.[iii]

In hindsight, I should have been marginally more circumspect. If the way you raise your kids has little effect on the number of grandkids you get, perhaps you should do ten times as much to encourage your kids’ fertility. My parents (bizarrely!) discouraged fertility with their habitual complaining about the hardships of parenting. I do the opposite, leading with the mantra, “Since I had four kids, I am entitled to sixteen grandkids.”

In any case, in recent years I’ve started to hear a more fundamental objection to the idea that genes explain almost all family resemblance in fertility. Namely: There is no family resemblance to explain. Alternately, perhaps there used to be family resemblance to explain, but no longer.

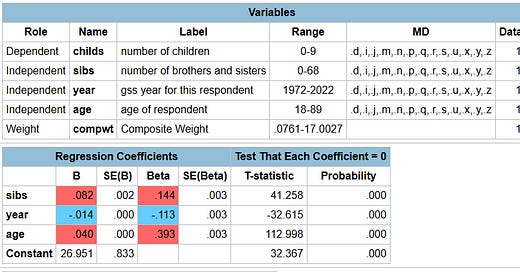

I recently decided to investigate this claim in the General Social Survey. (All respondents reside in the United States; if you have comparable results from other countries, please share in the comments). Specifically, I regressed number of children on the year of the survey, the respondent’s age, and the respondent’s number of siblings. Results from 1972-2022:

The effect is modest — every extra sibling predicts .082 additional offspring. But since every human has two parents, you could argue that the “true” effect is in some sense 2*.082=.164.

But is that .082 coefficient in steep decline, a vestige of an older world when fertility bred fertility? Actually, the opposite is true. The coefficient for the 21st century is actually larger than it was in the 20th. Compare and contrast…

The 20th Century

to…

The 21st Century

Yes, the estimated effect size grew almost 30%, from .073—>.094. Yes, both are marginal effects. But at least in the U.S., “people from larger families ultimately have more kids” isn’t just true. It’s getting truer.

If you read the results more closely, you’ll see the news isn’t all good. Look at the coefficient on year. The fertility fall was already negative for 1972-1998, but the slope almost doubled in absolute value for 2000-2022. Four years of anti-natal cultural change more than wipes out the pro-natal effect of a full extra sibling. At least for now.

Notes from SRtHMK

[i] “A major study of Danish twins born 1870-1910 found moderate nurture effects on family size.” Hans-Peter Kohler et al., “Is Fertility Behavior in Our Genes? Findings from a Danish Study.” Population and Development Review 1999.

[ii] “Upbringing had a tiny influence on when Danes tried to start a family...” Joseph Rodgers et al., “Behavior Genetic Modeling of Human Fertility: Findings from a Contemporary Danish Twin Study.” Demography 2001, p.36.

[iii] “A different team of researchers looked at about 2000 American twins, siblings, half-siblings and cousins...” Joseph Rodgers and Debby Doughty, “Genetic and Environmental Influences on Fertility Expectations and Outcomes Using NLSY Kinship Data,” in Joseph Rodgers et al., Genetic Influences on Human Fertility and Sexuality. Springer, 2000.

I think linear regression is very hard to read in this sort of study. I personally would group number of children into: 0; 1; 2; 3; 4 or more. I would also be careful about having the adults be age 40 or more in the year surveyed (maybe even 45 or more). Then I would look at transition probabilities. How many people who came from a family with 1 child ended up with 0 children, 1 child, 2, children, 3 children, or 4 or more children? The same with people who came from a family of 2 children; of three children; of 4 or more children.

Then you might look at how that changes by birth year.

My father would tell us that he wants 121 grandchildren, 11 from each of his 11 children. He only got 52.