Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Spolaore and Wacziarg

Welcome to the third installment of the EconLog Reading Club on Ancestry and Long-Run Growth. This week’s paper: Spolaore, Enrico, and Roman Wacziarg. “How Deep Are the Roots of Economic Development?” Journal of Economic Literature 51 (2): 325-369. The authors’ data is here.

Summary

Spolaore and Wacziarg survey a broad literature on long-run growth, paying special attention to measures of ancestry. They begin by surveying the evidence on the strong long-run effects of geography: absolute latitude and islands are good for prosperity, tropics and being landlocked are bad. They then cover and critique Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson’s famous “reversal of fortune” paper. According to SW, ARJ’s results are fragile:

[W]hen Europe is included in the sample, any evidence for reversals of fortune disappears: the coefficient on 1500 population density is essentially zero for the broadest sample that includes the whole world (column 1). For countries that were not former European colonies, there is strong evidence of persistence, with a positive significant coefficient on 1500 density. The evidence of persistence is even stronger when looking at countries that are populated mostly by their indigenous populations (the evidence is yet stronger when defining “indigenous” countries more strictly, for instance requiring that more than 90 percent of the population be descended from those who inhabited the country in 1500).

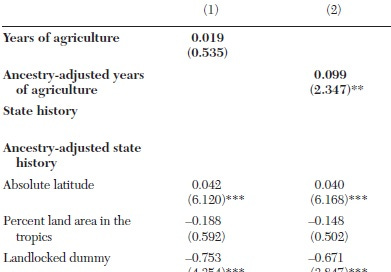

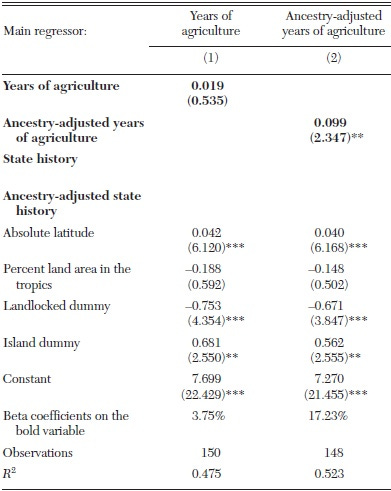

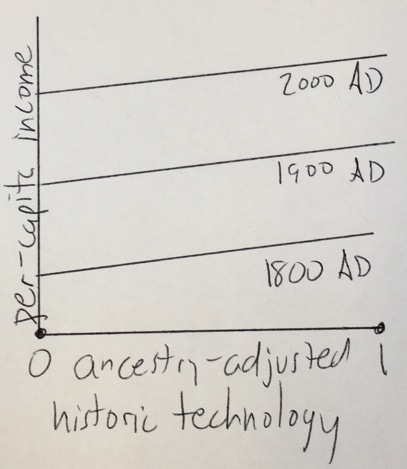

This in turn leads SW into the work this Read Club has already covered. But rather than simply cite them, SW tweak their regressions and report the results. Log per capita income in 2005 is the dependent variable.

First, agricultural measures:

Second, state history measures:

Both sets of regressions reinforce the lessons of Putterman and Weil: ancestry and geography are both big deals. If I’m correctly applying SW, though, they find a smaller effect of ancestry and a larger effect of geography, presumably because they add the “Island” variable. An extra 10,000 years of ancestral agriculture boosts expected per-capita income by 269%. But moving 25 degrees from the equator has the same effect. And moving from a landlocked country to an island at the same latitude boosts per-capita income by 343%!

For ancestral state history, similarly, going from the min to the max raises per-capita income by 337%. But moving 26 degrees from the equator does the same, and moving from a landlocked country to an island at the same latitude boosts per-capita income by 288%.

SW then move into their own work on genetic distance. What’s genetic distance?

Genetic distance is a summary measure of differences in allele frequencies between populations across a range of neutral genes (chromosomal loci). The measure we used, FST genetic distance, captures the length of time since two populations became separated from each other. When two populations split apart, random genetic mutations result in genetic differentiation over time. The longer the separation time, the greater the genetic distance computed from a set of neutral genes. Therefore, genetic distance captures the time since two populations have shared common ancestors (the time since they were parts of the same population), and can be viewed as a summary measure of relatedness between populations.

Genetic distance from the United States turns out to be another highly-predictive ancestry measure – though, as usual, geography also matters enormously.

SW close the paper with a lengthy discussion of where the results come from and what they mean. Most notably, they ponder the distinction between “direct” and “barrier” effects of long-run forces:

One possibility is that intergenerationally transmitted traits have direct effects on productivity and economic performance. A slow-changing cultural trait developed in early history could be conducive directly to high incomes in modern times if it is transmitted from parents to kids within populations, either behaviorally or through complex symbolic systems (e.g., by religious teaching). For example, a direct effect stemming from cultural transmission would be Weber’s (1905) argument that the Protestant ethic was a causal factor in industrialization (a recent critical reassessment of this hypothesis has been provided by Becker and Woessmann 2009).

As we discussed in the previous section, another possibility is that human traits act to hinder development through a barrier effect. In this case, it is not the trait itself that directly affects economic performance. Rather, it is differences in inherited characteristics across populations that create barriers to the flow of technological and institutional innovations, ideas, etc., and, consequently, hurt development. Historically rooted differences may generate barriers–e.g., via cultural, racial, and ethnic bias, discrimination, mistrust, and miscommunication–hindering interactions between populations that could result in a quicker diffusion of productivity enhancing innovations across populations…

SW close by trying to prevent misinterpretation of the research. Yes,

Taking the recent literature seriously implies acknowledging the limits faced by policymakers in significantly altering the wealth of nations when history casts a very long shadow. A realistic understanding of the role of historical factors is essential for policy assessment. One could obtain misleading conclusions about the effects of specific policies and institutions when not taking into account the role of long-term variables.

But the fraction of variance explained by long-run forces is way below 1, and many countries have broken out of bad long-run trajectories.

Critical Comments

1. Overall, I have less to say about SW because most of my earlier critical comments transfer over. Besides introducing the economics profession to a lot of interesting research, SW’s main value-added is providing outside verification that ancestry regressions are robust. All the main results we’ve reviewed hold up: ancestry matters a lot, even controlling for geography, but geography is also greatly important, controlling for ancestry.

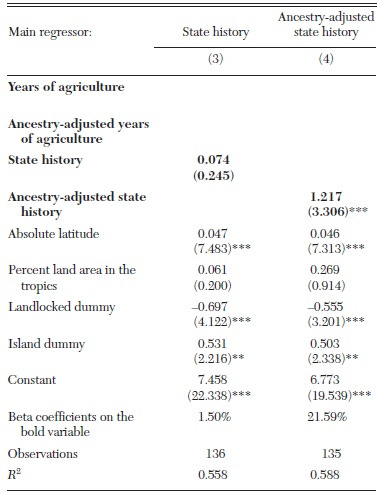

2. SW’s caveats are understated. All their regressions – and as far as I can tell, all the research they discuss – try to explain why some countries are richer than others. None of them even whisper that some countries are doomed to absolute poverty. The amazing economic history of the last two centuries shows the opposite. While relative performance is fairly stable, absolute performance has skyrocketed. Remember last week’s graph:

The same holds if we put any of the key ancestry measures on the x-axis: In any given year, countries with more successful ancestors do better. Over time, however, the whole success curve is rapidly shifting up.

To be fair, SW are writing in an intellectual environment where the basic facts of exploding global prosperity are well-known. But non-economists who read SW are dangerously likely to embrace a misguided fatalism.

3. Once again: If we take all of SW’s results seriously – ancestry and geography – the case for free migration gets stronger, not weaker. Global economic growth will end absolute poverty eventually, but all this research confirms that moving the world’s poor to rich countries is an amazing short-cut.

The post appeared first on Econlib.