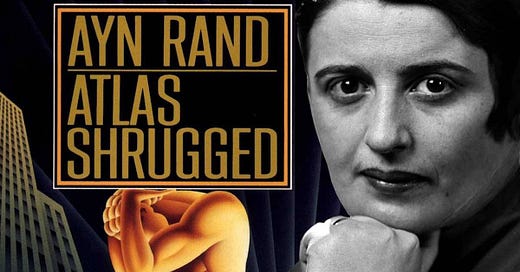

Anti-State is Anti-Freedom, Part 1

Yaron Brook and Don Watkins against anarcho-capitalism

Last September, I debated Yaron Brook of the Ayn Rand Institute at the Soho Forum on anarcho-capitalism. Here’s my opening statement, full debate video, and my post-debate reflections. As usual, I offered my opponent the chance to reply in his own words. Here (in two parts, due to length) is Brook’s reply, co-authored with Don Watkins. To be honest, I find their response rather unresponsive, but judge for yourself.

How do we liberate individuals from the rule of brute force and create a free society? The main answer coming out of the classic liberal tradition is that we establish a constitutionally limited government devoted to the protection of individual rights.

Libertarian anarchists take a different view. They argue that getting rid of government will—or at least could—unleash “market competition” among “private defense agencies” that will protect freedom better than any limited government has or could.

These anarchists have come to dominate the libertarian movement, if not in numbers than in influence. Even libertarians who are not anarchists typically express sympathy. Anarchy, they say, is an impractical ideal—but an ideal nonetheless. The closer we can get to dismantling the state, the better.

We disagree. We come at this issue, not as libertarians, but as Objectivists—advocates of Ayn Rand’s philosophy. One of the major reasons Objectivists have gone to great pains to distinguish ourselves from libertarians is that they make common cause with anarchists. On our view, anarchy does not lead to anything like freedom: it means and has to mean the rule of brute force. A rights-protecting government, by contrast, is neither an unnecessary evil nor a necessary evil, but a positive good.

What Freedom Is

A free society is not a society where you can do whatever you want—it is a society that subordinates might to right. That is the function of individual rights. In Rand’s formulation:

“Rights” are a moral concept—the concept that provides a logical transition from the principles guiding an individual’s actions to the principles guiding his relationship with others—the concept that preserves and protects individual morality in a social context—the link between the moral code of a man and the legal code of a society, between ethics and politics. Individual rights are the means of subordinating society to moral law.[1]

Political freedom follows from a moral perspective that values the individual and aims at his flourishing. At the most basic level, human beings flourish through thought and production. We use reason to discover what’s true and what’s good, and we use that knowledge to build secure, fulfilling lives—chiefly through the creation of material values.[2]

That’s true even of a human being living alone on an island. But human beings live best in society, where they can benefit from the thought and production of billions of other people. Not any society, however, will aid in human flourishing: it is far safer to live alone on an island than in Afghanistan or North Korea. Human beings thrive in rational, productive, free societies.[3]

How do we create a society that safeguards an individual’s pursuit of life and happiness through thought and production? How do we create a society that allows individuals to gain the benefits of living in society while avoiding the potential harms? We define and protect the individual’s right to live a moral life. Rights are moral principles—not principles governing what each individual ought to do, but what an individual ought to be free to do in society.

If it is right that the individual seek to preserve his life, then we should organize society so that each individual is free to preserve his life. If it is right that the individual think, then we should organize society so that each individual has the liberty to exercise his own judgment. If it is right that the individual produce, then we should organize society so that each individual is free to earn and use property. If it is right that the individual seek his own happiness, then we should organize society so that each individual is free to pursue his own happiness. The rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness form the guiding principles for creating a free society.

There is only one way to violate these rights: the initiation of physical force.[4] Force is not the only harm other people can inflict on us, but it is a unique harm: it is the only harm that renders us incapable of living according to our own thought and effort. To be sure, we can think about how to avoid force or how to respond to it, but to the extent we are at the mercy of a murder, a rapist, or a thief, we are not free to live according to our own judgment. When a boss fires us or a partner cheats on us, the results may be more devastating than getting punched in the arm, but we remain free to try to repair the relationship or go our own way. Going our own way is precisely what we cannot do in the face of physical force.

The initiation of physical force includes, most obviously, direct physical contact with someone against their consent. But it also includes indirect deployments of force—especially the threat of force. “Your money or your life” represents the initiation of force, even if the thief never pulls the trigger. The IRS seizes your income by force, even if you mail the check and armed agents never show up at your home. Such “transactions” only take place because they are backed by the promise of direct force. Similarly, menacing constitutes the initiation of force. If a man storms into a restaurant waving a gun in the air, you are not free to go about your business, and you do not have to wait for the bullet to come flying at you before acting in self-defense.

A society that protects individual rights from violation by force is a free society. Free individuals may face any number of challenges and obstacles on the path to achieving happiness—but no one can use force to stop them from pursuing their happiness through thought, production, and voluntary cooperation with other people.

Why a Rights-Protecting Government is Necessary

To protect individual rights, a society must do two things.

It must define the individual’s rights in a legal code so the individual knows his sphere of freedom and what actions might violate the rights of others

It must enforce that legal code through retaliatory force, which itself must be governed by rights-protecting laws

The rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness name our fundamental rights. But these rights are too abstract to provide us with all the knowledge we need to function in a society.

For example, does your right to property give you the right to oil far beneath your house, or does that right belong to the oil company that discovers the deposit and accesses it through horizontal drilling? Does an embryo have a right to life—or does that right belong only to the mother? If you write a novel or design a new technology, can your neighbor copy your creation and sell it—or is he violating your intellectual property rights? Can you build a road around someone’s house and charge her a million dollars to cross, or is she entitled to an easement?

If human beings are to live among each other without conflict and chaos, these and countless other such questions have to be answered. They cannot be answered by reading them off from our fundamental rights—and they certainly cannot be answered by deducing them from some “non-aggression axiom.” Beyond certain clear-cut cases, like punching a stranger in the face unprovoked, what counts as aggression usually can’t be determined until our rights are specifically defined. To define our rights in the necessary detail, lawmakers and jurists must translate our fundamental rights into a legal code.

But a legal code is only a legal code if it is enforced. A law against murder is only a law if murderers face punishment. This requires the use of retaliatory force.

In a free society, human beings deal with one another through voluntary persuasion or they go their separate ways. The person who resorts to force doesn’t allow men to go their own way. He refuses to deal with human beings by reason and so he must be answered by force. In Rand’s formulation:

It is only as retaliation that force may be used and only against the man who starts its use. No, I do not share his evil or sink to his concept of morality: I merely grant him his choice, destruction, the only destruction he had the right to choose: his own. He uses force to seize a value; I use it only to destroy destruction.[5]

But just as we need laws to define our sphere of freedom, we need laws governing the use of retaliatory force. This includes procedural laws governing how a crime is investigated, when an arrest can be made, how a trial is conducted, how guilt is determined, and how punishment and restitution are determined. Each of these steps creates the potential for initiating force against innocent parties. For example, a suspected murder lives with his parents. Can detectives search the suspect’s room? The entire house? The neighbor’s adjacent property the suspect may have crossed on the night of the murder? Detain and question his parents? To ensure force is used only in retaliation, these and countless other decisions must be determined, not by the whim of investigators, but by law.

Such laws not only ensure, so far as possible, that only the guilty are penalized—they allow other members of society to know the use of force is retaliatory. Remember, the threat of force is force. If you march into town and gun down Bill in the street because you say he murdered your cousin, it is irrelevant that you know in your own mind Bill is a killer. From the perspective of bystanders, you are a threat. It’s only when retaliatory force is deployed according to defined laws, and the public can see that this is so, that there is a clear demarcation between the initiation of force and the retaliatory use of force.

The institution we create to define and enforce rights-protecting laws is government. “A government,” writes Rand, “is an institution that holds the exclusive power to enforce certain rules of social conduct in a given geographical area.” It “is the means of placing the retaliatory use of physical force under objective control—i.e., under objectively defined laws.”[6]

The need for geographical exclusivity is built into the purpose of law. The purpose of rights-protecting laws is to organize society and so they must extend over a society—over a geographic region where people can live securely in their rights. This region, then, must be large enough for an individual to build a life in. If different laws govern your interactions with each of your neighbors or each of your roommates, or if they differ from neighborhood to neighborhood or block to block, the result would not be clarity and peaceful coexistence but chaos and perpetual conflict.

Anarchists will often point to interactions between citizens of different countries as counterexamples allegedly demonstrating that geographical sovereignty is unimportant. But these interactions almost always occur under the jurisdiction of one government or another. Where neither country has jurisdiction, we don’t see complex commercial interactions, but high-risk interactions that can hardly be called “free.”

Government is a tool: it’s an institution created by individuals and should be used to protect their rights so they can live and flourish in a free society. A government that fulfills its proper function is not a necessary evil because it is not an evil. It is a force for good. It does not limit people’s freedom but in a very real sense creates their freedom.

Man, in a “state of nature,” is not free. He is subject to coercion from any person (or gang) stronger or more ruthless. Man, in a society safeguarded by a rights-protecting government, is free. He can think, produce, trade, live free from force.

Why A Rights-Protecting Government Is Possible

Anarchists argue that a proper, rights-protecting government is a fantasy: either it is outright impossible or highly improbable.

A proper government is impossible, anarchists claim, because a government must initiate force against “competitors.” Philosopher Michael Huemer summarizes the argument:

Government, by definition, holds a monopoly on the services it provides. It maintains this monopoly through the use of force against anyone who attempts to compete—that is, anyone who attempts to provide the same services as the government. Now, either the provision of these services constitutes aggression, or it does not. If it constitutes aggression, then, by the Non-Aggression Axiom, government is unjustified. But if it does not constitute aggression, then to use force to prevent other people from providing these services is itself to commit aggression. In other words, if the state violates rights, then it must be abolished; if the state does not violate rights, then it can have no valid objection to other organizations doing the same thing as the state is doing.[7]

This objection fails apart under the most cursory scrutiny.[8] A rights-protecting government defines the procedures governing the use of retaliatory force, including the personnel empowered to carry out these procedures. The rights of a judge are not violated because he cannot also act as arresting officer, prosecuting attorney, jury, and executioner.

What anarchists describe is not a situation where someone is providing the same “service” as a government, the way one might offer the same service as one’s neighborhood barber. They describe a situation in which someone wants to deploy the use of force unilaterally, without legal authorization. In a free society, or anything close to a free society, no one has such a right, and so the government is not violating their rights by stopping them.[9]

If an individual resorts to the unilateral use of force, it does not matter if he believes himself to be using force to protect rights. He is using force in defiance of the legal safeguards that establish retaliatory force as retaliatory. Like the man who guns down a supposed murderer in the street, he is by that very fact a threat to other citizens, and the government must stop that threat to defend its citizens’ rights.

There is no right to the arbitrary use of force, and force is used arbitrarily whenever it is not used according to the procedures defined in an objective legal code.

But even if a proper government is possible, is it probable? Anarchists claim that Objectivists cannot point to examples of proper, rights-protecting governments—but the anarchist, by contrast, can point to countless examples of governments that violate rights.

This is true but utterly beside the point. What Objectivists can point to are abundant partial examples of governments placing the use of force under objective laws aimed at the protection of individual rights. And if governments can do this partially, there is nothing stopping them from doing it consistently.

Objectivists often point to late 19th century America as approximating an ideal government, but we can also point to America today, or Canada, or Germany, or Sweden, or Japan, or South Korea. All these countries, whatever their flaws, are nothing like Iran, North Korea, or Hamas. They have established governments with more or less limited powers that mostly operate according to the rule of law, with many of those laws aimed at the protection of individual rights. From an historical perspective, these governments have done an admirable job establishing societies where people coexist peacefully and can live self-directed lives. They are far from ideal—but they are even farther from authoritarian regimes that do more to threaten their citizens than to protect them.

What we don’t have—not in any way to any extent—are examples of rights-protecting anarchic societies.

“But Medieval Iceland!” But Medieval nothing. No one can claim that Iceland’s primitive, tribal, brutal society achieved anything like a legal code that protected individual rights. The most anarchists can muster is that it achieved a similar amount of poverty and stagnation as its neighbors.[10] Its only distinction is that it managed to stagnate without a state, which counts as an achievement only if your standard for successful social organization is that there be no government.

Nor do the relationships between different countries offer a model for the relationship between individuals under anarchy. The peaceful dealings we see between the US and Canada, for instance, are made possible by the fact that they are governments with the exclusive power to enforce laws in a defined geographical area. Many conflicts between countries originate over contested territory. And the only reason anyone could mistake international relations for a model of peaceful coexistence is that the US has been the world’s dominant superpower since World War II. When there is no rights respecting (mostly) dominant power, international relations have historically been defined by conflict, not cooperation. If anything, international relations illustrate the value of a monopoly on force.[11]

We don’t need to look to examples borrowed from the governed world or to an historical aberration like Iceland to see what anarchy looks like in practice. Anarchy has a long track record—and it is ugly. Anarchy exists wherever there is no government able to establish a monopoly on the use of force. It exists in every gang-run neighborhood and in every prison. It existed in Somalia, in Lebanon, in the countries being torn apart by warring narco cartels. Anarchy is so unlivable that human beings have generally preferred to live under the heel of oppressive governments rather than be caught in the crossfire of warring gangs.

Libertarian anarchists disclaim all of these examples: their theory would unleash anarchy in a form that looks nothing like anarchy as it has actually existed. We must not look to history or to the world today to judge their theory. We must judge their theory on its own merits. Fine. Let’s consider their theory and what it has to say about how force should be used.

[1] Ayn Rand, “Man’s Rights.” For an accessible introduction to the Objectivist view of rights, freedom, and government aimed mainly at libertarians, see Onkar Ghate and Greg Salmieri’s lecture series, “What is Liberty?” We also cover these issues in our book Free Market Revolution.

[2] See Ayn Rand, “The Objective Ethics.”

[3] Ayn Rand, “The Objective Ethics.”

[4] For a full treatment of this issue from an Objectivist perspective, see Darryl Wright’s three chapters on force in Foundations of a Free Society.

[5] Ayn Rand, “Retaliatory Force.”

[6] Ayn Rand, “The Nature of Government.”

[7] Michael Huemer, “Defending Liberty,” in Foundations of a Free Society.

[8] On this argument, see also Harry Binswanger, “Objectivism vs. Anarchism.”

[9] Onkar Ghate notes that someone “would have a legitimate objection that he is being prohibited from exercising his right of self-defense only if he were banned from making use of the government apparatus that has been erected—as, for instance, was the case for ‘colored’ people in the Jim Crow South.” See Onkar Ghate, “Rand (contra Nozick) on Individual Rights and the Emergence and Justification of Government,” in Foundations of a Free Society.

[10] Vincent Geloso and Peter T. Leeson, “Are Anarcho-Capitalists Insane? Medieval Icelandic Conflict Institutions in Comparative Perspective.”

[11] This doesn’t mean, however, that a one-world government is desirable. To name just one reason, since no single country is ever guaranteed to remain free, having multiple governments increases the chances there will remain free societies somewhere on the globe, without undermining the sovereignty that the protection of individual rights demand.

Watkins makes the case eloquently and convincingly. I've never understood how anarchy is not the same thing as civil war.

The Founding Father understood well that no man must be allowed to be the sole arbitrator of a dispute in which he is involved. The Objectivist defense of the state is merely a more consistent and philosophically grounded defense of that position.