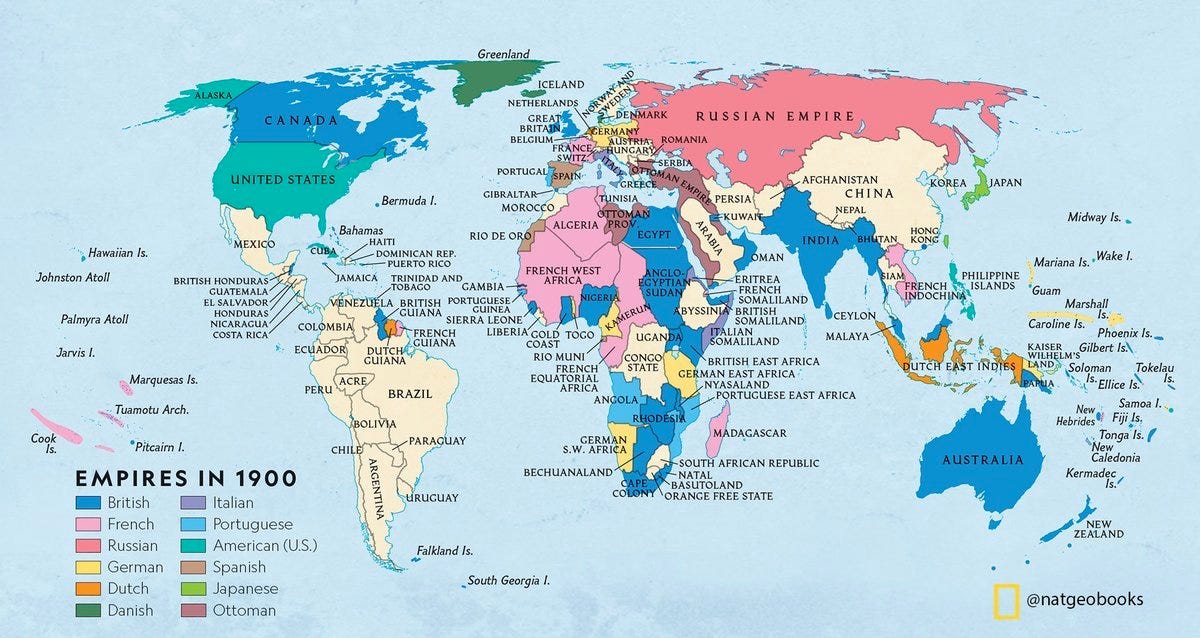

Some historians argue that colonialism was an outgrowth of nationalism. Once the people in the leading industrial powers started to strongly identify as British, French, German, American, or Japanese, they fell in love with the idea of planting their national flags all over the map. Hence, “empire.”

Other historians argue that anti-colonialism was an outgrowth of nationalism. Once people in Asia and Africa started to strongly identify as Indian, Malaysian, Egyptian, Algerian, or Angolan, they fell in love with the idea of replacing the foreign flags on the map with their own. Hence, “national liberation.”

A thinly-veiled political agenda usually stands behind these claims. Most people nowadays agree that colonialism was bad. So if nationalism leads to colonialism, that’s a mark against nationalism; but if nationalism leads to anti-colonialism, that’s a mark in favor of nationalism. Lingering fans of colonialism naturally reverse these scoring rules.

So who’s right about the connection between nationalism and colonialism? As far as I can tell, both sides are right. Nationalism inspired many of the world’s mightiest countries to attack and annex the world’s economic laggards. But this in turn exposed the inhabitants of the colonies to the idea of nationalism. Before long, native thinkers were marketing their locally-made variants – and calling for national liberation. Once the colonial powers lost the stomach for draconian repression, the anti-colonial movement swiftly triumphed.

If nationalism inspired two incompatible movements, how should we evaluate it? You might just call it a wash: Nationalism giveth, and nationalism taketh away. But this shoulder shrug overlooks two mountains of bodies. The first mountain: All the people killed to establish colonial rule. The second mountain: All the people killed to overthrow colonial rule. It is perfectly fair to blame nationalism for both “transition costs.”

Surprising implication: Regardless of the relative merits of colonial versus indigenous rule, the history of colonialism makes nationalism look very bad indeed. Why? Because colonial rule didn’t last! So if you’re pro-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral wonders, followed by another high transition cost. And if you’re anti-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral horrors, followed by another high transition cost. Two dreadful deals, however you slice it.

But don’t you either have to be pro-colonial or anti-colonial? No. You can take the cynical view that foreign and native rule are about equally bad. You can take the pacifist view that the difference between foreign and native rule isn’t worth a war. Or, like me, you can merge these positions into cynical pacifism. On this view, fighting wars to start colonial rule was one monstrous crime – and fighting wars to end colonial rule was another. Nationalism is intellectually guilty on both counts, because it is nationalism that convinced people around the world that squares of multi-colored cloth are worth killing for.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

"Nationalism" had very little to do with colonialism, "national self-interest" had a great deal to do with it. Very silly mistake to confuse the two.

Although fighting for a different rule may not be worth the bloodshed, fighting for a better rule might be a different story. And one could argue that a rule more decentralized & closer to its subjects, is more likely to be more lenient & freedom-friendly, than the governship of a distant, centralized authority.