In January, Bet On It readers voted for two audits of Alex Epstein’s Fossil Future. First topic: Is Epstein correct to claim that climate models have been too pessimistic; i.e., that they have overpredicted global warming? Specifically:

“Epstein says that climate models are excessively pessimistic. These links argue that they have been accurate.” https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2019GL085378

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2018/06/30-years-after-hansens-testimony/

To start, let’s carefully read precisely what Epstein claims. In the section titled “The Limited, Masterable, and Speculative Amplified Greenhouse Effect,” he states:

There are three crucial things to recognize about the positive feedback loops that supposedly contribute to a significantly amplified greenhouse effect: (1) they are limited by the diminishing nature of the greenhouse effect, (2) even extreme projections of warming would be masterable, and (3) the extreme projections are highly speculative and unlikely to come true.

Epstein names three reasons to accept (3):

1. Even catastrophist organizations like the IPCC admit that extreme climate CO2 sensitivity is highly speculative.

2. The temperature record supports a much more mild climate CO2 sensitivity.

3. There are myriad ways in which the climate predictors are inclined and incentivized to make extreme predictions

In arguing for (3.1), Epstein explains:

This is a suspicious deviation from most previous assessment reports, which provided an estimated range of 1.5– 4.5°C— suspicious because past models were already projecting more warming than has occurred.(10) So why do the latest models project even more warming? The increased estimate likely reflects the bias of the models and modelers toward more extreme scenarios rather than toward a better understanding of the climate system.

A little later, he adds:

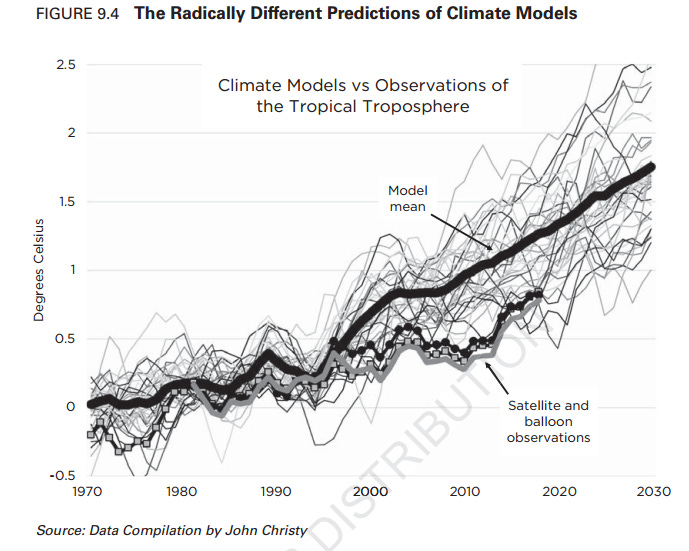

The following page shows a graph of prominent modern climate models for the lowest layer of the atmosphere, put together by John Christy of the University of Alabama at Huntsville, who collects satellite measurements of temperature. Christy assembled this graph to show that most of these models have significantly overpredicted warming.

Here’s the graph.

On my reading, this audit is specifically about one important subset of (3.1). Namely: Is it really true that models were overly pessimistic in the past? Epstein’s documentation appears in chapter 7, endnote 10:

IPCC, AR6 Climate Change 2021; IPCC, The Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary for Policymakers, 16, Ross McKitrick, “New Confirmation That Climate Models Overstate Atmospheric Warming,” Climate Etc. (blog), accessed September 18, 2021.

The last-named Climate Etc. blog post, in turn, provides detailed discussion of two articles:

Mitchell et al. (2020) “The vertical profile of recent tropical temperature trends: Persistent model biases in the context of internal variability” Environmental Research Letters.

McKitrick and Christy (2020) “Pervasive warming bias in CMIP6 tropospheric layers” Earth and Space Science.

To conduct my audit, I read the two reader-recommended pieces, plus the relevant section of the Working Group I Contribution, plus Mitchel et al. (2020) and McKitrick and Christy (2020). Here is what I learned:

The first reader-recommended piece, Hausfather et al.’s 2019 “Evaluating the Performance of Past Climate Model Projections,” in Geophysical Research Letters, seems totally inconsistent with Epstein on the surface. The abstract states:

We find that climate models published over the past five decades were skillful in predicting subsequent GMST changes, with most models examined showing warming consistent with observations, particularly when mismatches between model-projected and observationally estimated forcings were taken into account.

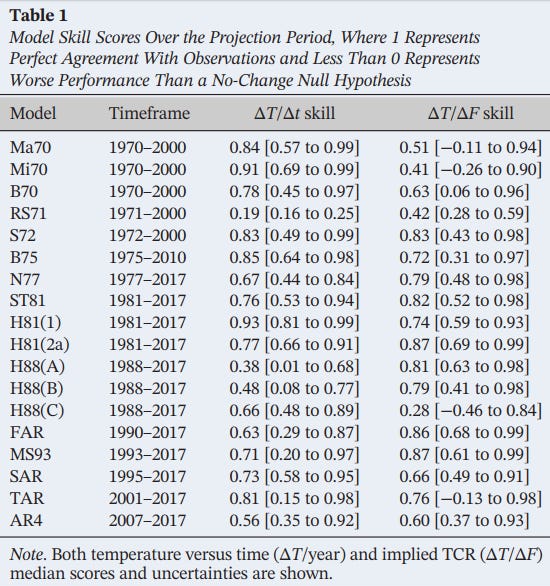

What immediately troubled me: The abstract offers a binary verdict (“consistent with observations”) rather than a continuous verdict. I was hoping for something like, “On a scale where maximum error equals -1 and perfect prediction equals +1, the average model gets a +.83".” On page 7, however, the paper’s Table 1 does offer such results.

These scores look pretty good, but hardly amazing. How low would the scores have to be before the authors said they weren’t “consistent with observations”?

Hausfather et al. also has a detailed discussion of the prominent H88 model. Their graph:

This is consistent with Epstein’s exact point: Until about 2015, warming was usually below the most optimistic (coolest) scenario. Hausfather et al. concede this, but argues that the model only overpredicted warming because researchers overpredicted greenhouse gas emissions:

H88's “most plausible” Scenario B overestimated warming experienced subsequent to publication by around 54% (Figure 3). However, much of this mismatch was due to overestimating future external forcing—particularly from CH4 and halocarbons (Figure S3). When H88 Scenario B is evaluated based on the relationship between projected temperatures and projected forcings, the results are consistent with observations (Figures 2 and 3).

The second reader-recommended piece, written by one of the co-authors of Hausfather et al., repeats the previous summary: Yes, warming was at the low end of the models’ scenarios:

The modeled changes were as follows:

Scenario A: 0.33±0.03ºC/decade (95% CI)

Scenario B: 0.28±0.03ºC/decade (95% CI)

Scenario C: 0.16±0.03ºC/decade (95% CI)

The observed changes 1984-2017 are 0.19±0.03ºC/decade (GISTEMP), or 0.21±0.03ºC/decade (Cowtan and Way), lying between Scenario B and C, and notably smaller than Scenario A.

But:

Estimates of CO2 growth in Scenarios A and B were quite good, but estimates of N2O and CH4 overshot what happened (estimates of global CH4 have been revised down since the 1980s). CFCs were similarly overestimated (except in scenario C which was surprisingly prescient!).

The relevant part of the Working Group I report initially seems inconsistent with Epstein: “The long-term climate model simulations show a trend in global-mean surface temperature from 1951 to 2012 that agrees with the observed trend (very high confidence). There are, however, differences between simulated and observed trends over periods as short as 10 to 15 years (e.g., 1998 to 2012).” But the very next paragraph shows the report uses a low bar for “agrees with the observed trend”:

The observed reduction in surface warming trend over the period 1998 to 2012 as compared to the period 1951 to 2012, is due in roughly equal measure to a reduced trend in radiative forcing and a cooling contribution from natural internal variability, which includes a possible redistribution of heat within the ocean (medium confidence). The reduced trend in radiative forcing is primarily due to volcanic eruptions and the timing of the downward phase of the 11-year solar cycle. However, there is low confidence in quantifying the role of changes in radiative forcing in causing the reduced warming trend.

Which seems to support Epstein’s conclusion.

Mitchell et al. made me realize I needed to read all these sources more cautiously. The pieces readers recommended are talking about surface temperature warming. Mitchell et al., in contrast, are focused on warming at higher parts of the atmosphere - the upper troposphere and the lower-middle stratosphere. At those atmospheric levels, this research team unambiguously say that past models seriously overstate warming. (They add, “these biases can be linked to biases in surface warming,” but they don’t elaborate). As long as surface temperature models are accurate, should we care what happens further up? Probably; if standard models make major errors for topics that matter less, that still undermines their credibility for issues that matter more.

McKitrick and Christy are also talking about the troposphere. From the Plain Language Summary of the paper:

It has long been known that previous generations of climate models exhibit excessive warming rates in the tropical troposphere. With the release of the CMIP6 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Version 6) climate model archive we can now update the comparison… What was previously a tropical bias is now global. All model runs warmed faster than observations in the lower troposphere and midtroposphere, in the tropics, and globally. On average, and in most individual cases, the trend difference is significant. Warming trends in models tend to rise with the model Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS), and we present evidence that the distribution of ECS values across the model is unrealistically high.

How does Epstein do in the audit? To start with basic housekeeping, all his cites check out. He’s being careful, and he’s not making anything up.

The reader-supplied cites actually appear consistent with Epstein’s claim that “past models were already projecting more warming than has occurred.” Epstein refrained from making hyperbolic claims in the first place. So when Hausfather et al. argue that past predictions would have been right if they’d measured greenhouse emissions better, they’re not contradicting Epstein.

Mitchell et al. and McKitrick and Christy both seem to strongly support Epstein. And if you do a background check, they all seem like eminent mainstream climate researchers, not cherry-picked eccentrics.

Still, I suspect that alarmists will fault Epstein for “bait-and-switch.” When most people say “warming,” they mean surface warming, not warming higher up in the atmosphere. But this is clearly relevant for the general accuracy of climate models. The worst I’d say about Epstein is that he should have underscored the distinction between surface temperature and tropospheric temperature more clearly.

When I asked Epstein about this issue, Steffen Henne, his Head of Research, sent this reply. Reprinted with permission.

Models represent both the surface and the atmosphere (and all other variables like precipitation), they are not separate sets of models.

If satellite observations of the lower troposphere are used, they provide a warming trend in the observations, which is very close to that of the surface temperature data observed. Surface station observations obviously cannot evaluate atmospheric temperatures, but the bias in atmospheric temperatures is closely related to the surface bias. As Mitchell et al. (2020) observe: "we find considerable warming biases in the CMIP6 modeled trends, and we show that these biases are linked to biases in surface temperature" (This is present in the IPCC's AR6, so the climate community is well aware of it).

The greenhouse effect is most prominent in parts of the tropical troposphere, so for model performance evaluation this is the place to look at. But it's not separate from surface temperatures, as the models show biases in both, contradict each other in both (each model has a different climate sensitivity for greenhouse gases, i.e. a different warming rate per doubling of CO2), and simulate both at once.

Furthermore:

Surface temperatures are created by using surface station data (~1m above ground) and sea surface measurements. This is different from atmospheric measurements. The troposphere is the lowest layer of the atmosphere, reaching up several km. This is where most of the mass and almost all of the weather phenomena of the atmosphere are concentrated. This is useful to check on climate models because the tropical troposphere will show the strongest greenhouse effects. The media representation of the IPCC focuses on global average surface temperature (one temperature for the entire surface of the planet), which shows the least discrepancy with "hindcast" by models, as they are tuned to emulate this data.

The answer is no, figure 9.4 does not show the surface temperature. And it's because comparing surface temperature data to models is a biased comparison (that's why McKitrick and Christy / Mitchell et al. don't use it in the IPCC's AR6 for model performance evaluation). For the purposes of Fossil Future, this just happened to be the best data Christy provided and it doesn't really matter for the spread of model projections.

It is possible to derive a "surface" temperature with satellite data by using only the lower troposphere, which provides a warming trend very much in line with the various surface temperature products.

Overall, then, I say Epstein does very well in Audit 1. Although the pessimism of past climate models is hardly central to his case, Epstein is probably correct on the models’ surface temperature predictions and very likely correct on the models’ predictions for higher levels of the atmosphere. The claim that tropospheric measures of temperature are more relevant than surface measures is very plausible, but I would need to study the issue a lot more to really say.

Isn't the rhetorical point that Epstein is trying to support with his claim that climate models over predicted warming that we should be less concerned about the harms of fossil fuels?

That's not supported if the over prediction was the result of reducing emissions. What matters for that argument is how much warming we should expect for a given level of emissions.

I think you may be understating the importance of the experts' responses on points 2 and 3. They say their models overestimated warming because they overestimated "external forcing" -- in other words, how much carbon we put into the atmosphere. It seems to me that the most relevant question, and what people really want to know, is how responsive warming is to carbon emissions. If their model is essentially correct about that relationship, that's what matters most.