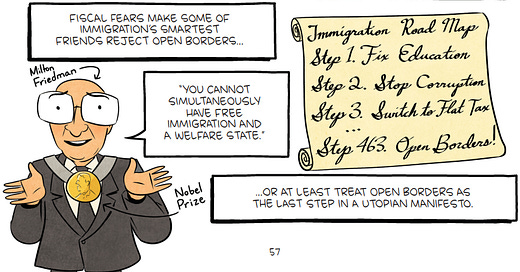

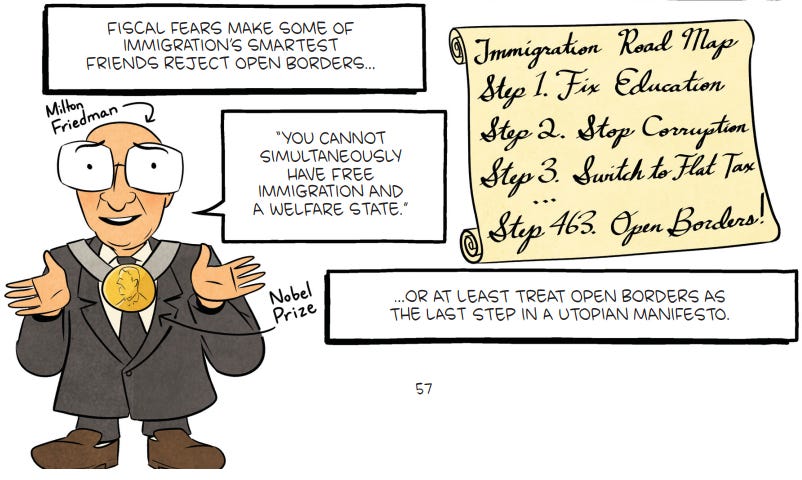

In 1999, the great Milton Friedman famously declared, “You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and free immigration.” But as we’ve seen, his supporting arguments were strangely weak. He was even taken aback by the very idea of guest worker visas: “And I haven't really thought about it a great deal, but my initial reaction is, that it's a very undesirable proposal.” A Pareto improvement is “undesirable”?!

The simplest explanation for Friedman’s uncharacteristically poor argumentation back in 1999 is his advanced age. Though still amazingly sharp for an 87-year-old, his powers had grown weak — especially when he had to think on his feet.

But is this the correct explanation? I recently discovered that Friedman also spoke at length about immigration in this 1978 talk, when he was still near his legendary intellectual peak. The excellent Connor Tabarrok helped me get the following transcript. I’ve split it into two parts, with the immigration-relevant sections in bold. Once Friedman’s best anti-immigration arguments are on the table, I’ll post a full response.

Let’s get started. Here’s Friedman on “What Is America?,” very lightly edited by me.

With respect to that title, which I admit, leaves you wondering what it's all about including me, I'll tell you what I really had in mind.

The title had to do with the question of whether America, by which I mean the United States of America, I mean our society, whether America is what it was, whether America is the land of opportunity, which produced over the past 200 years the greatest freedom and prosperity for the widest range of people that the world has ever seen, whether it still is the land in which people of many races, many beliefs, many origins are free to cooperate together to achieve their separate objectives, while at the same time retaining a diversity of values and opinions. Is that still America? Or is America not what it has been, not the land of promise of the past 200 years, but is it instead a land of growing bureaucracy and diminishing freedom? Is it a land of squabbling groups seeking to control the political levers of power, of divisive tendencies that are producing not merely variety, not merely diversity, but open conflict? Is it becoming instead a land of ethnic separatism rather than the land of the melting pot?

That's what I intended by this question and that is the theme of the whole series. I believe the choice is still open to us, that we can still decide, you and I and our fellow citizens, which of these two directions we want to go in, whether we want to return to the path that made this the great land of opportunity for millions and millions and millions of people, or whether instead we want to continue down the road toward a destruction of both liberty and prosperity. I believe very deeply that we are nearing the point of no return, that we still have the choice, but that if we continue much longer along the road that we have been going, we no longer shall have the choice, that we shall degenerate into a society which will lose that spark of creativity, that spark of independence, of freedom that we have all loved in our country.

In this lecture, I want to touch briefly on the achievements of the United States and the problems it faces, and then probe more deeply into the fundamental principles that, in my opinion, we must rely on to get back on the right track.

In other lectures of this series, I shall consider other general topics, but also specific problem areas. I have, as I say, chronologically, this is not the first, but logically it is.

If you look at the achievement of the United States I think the most dramatic example of it is in the field of agriculture. If you go back to the founding of this country in 1776, something like 80 to 90 percent of the people were on farms. It took 8 to 9 people working full time, 12, 16 hours a day to feed themselves and their families and perhaps one other person. Today, fewer than 5% of the American people are on farms. One person today can feed himself and his family and 19 others and their families, and also have a great deal left to export abroad. That is really, in a nutshell, the miracle of America.

In the modern idiom, if you say what made that possible, the first tendency of somebody would be to say, well, it must have been that there was a pretty smart and all-sighted government that was directing people what to do, that organized people's resources, but you and I know that the countries in the world where they have that kind of a government organizing their agriculture still have 40 to 50 percent of the people on farms and indeed are relying on us to feed them. And you know and I know that certainly for the first 150 and more years of this country's existence, government played a negligible role in this process.

After all, it was not until 1928, total government spending in this country never exceeded 10% of the national income. Total federal government spending never exceeded 3 percent of the national income, and most of that, of course, was for the Army and Navy. Of course, government did play an important role in providing a framework within which individuals could pursue their own values and their own interests. It even contributed in some small ways to agriculture in particular through things like extension service and the land grant colleges, but surely the major source of that enormous achievement was simply the fact that people were free to pursue their own interests in their own ways without interference from government.

That's the most dramatic and obvious exemplification of this miracle that was America, but you can look at it in a more general way. Here over the 19th century, into the 20th century, this country welcomed millions and millions of immigrants. I suspect that most of the people in this room today are descendants, 1st generation descendants, as I am, 2nd or 3rd generation descendants, then most of the people in this room are descendants of those immigrants who came to the United States from foreign lands with empty hands. I suppose there is a substantial exception because I see a good number of you who are citizens of other countries, and you are not descendants of those, but you are the modern way that we ought to be welcoming as immigrants in the same tradition which enabled the rest of us to get here.

You had a flood of immigrants, of millions of them coming to this country. What brought them here? It was a hope of a better life for themselves and their children. And in the main, they succeeded. It is hard to find any century in history in which so large a number of people experienced so great an improvement in the conditions of their life, in the opportunities open to them, as the period of the 19th and early 20th centuries. What was the source of this great achievement? Well, as has already been implicit in what I've said, the first and most important source was a set of values, a set of institutions that left people free to pursue their own interests according to their own lights.

But there was another factor of enormous importance that we no longer have today in the same degree, and that was the existence of two oceans that enabled us to follow George Washington's excellent advice to steer clear of foreign entanglements. And that certainly played an enormous role in enabling us to have those institutions and those arrangements that could let people develop their capacities. The result of these two factors together was that tremendous growth in production of which I've already spoken. The freedom from foreign entanglements, the fact that we could devote our attentions to our domestic problems, the free institutions promoted an outpouring of initiative, of innovation, of invention in every area. That's the achievement of the United States.

What is the basic problem of the United States today? The problem is that we are threatening to strangle this promise by government interference. Let me take as one example the feature I've already spoken of, free immigration. I have always been amused by a kind of a paradox. Suppose you go around and ask people, the United States, as you know, before 1914 had completely free immigration. Anybody could get on a boat and come to these shores, and if he landed on Ellis Island, he was an immigrant. Was that a good thing or a bad thing? You will find hardly a soul who will say it was a bad thing. Almost everybody will say it was a good thing, but then I suppose I say to the same people, but now what about today, do you think we should have free immigration? Oh no, they'll say, we couldn't possibly have free immigration today. Why, that would, that would flood us with immigrants from India, and God knows where, we'd be driven down to a bare subsistence level.

What's the difference? How can people be so inconsistent? Why is it that free immigration was a good thing before 1914 and free immigration is a bad thing today? Well, there's a sense in which that answer is right. There's a sense in which free immigration in the same sense as we had it before 1914 is not possible today. Why not? Because it is one thing to have free immigration to jobs. It is another thing to have free immigration to welfare, and you cannot have both if you have a welfare state, if you have a state in which every resident is promised a certain minimum level of income or a minimum level of subsistence regardless of whether he works or not, produces it or not, well, then it really is an impossible thing.

If you have free immigration in the way in which we had it before 1914, everybody benefited. The people who were here benefited. The people who came benefited because nobody would come unless he or his family thought he would do better here than he would elsewhere. And the new immigrants provided additional resources, provided additional possibilities for the people already here, so everybody can mutually benefit. But on the other hand, if you come under circumstances where each person is entitled to a pro-rated share of the pot, to take the extreme example, or even to a low level of the pot, then the effect of that situation is that free immigration would mean a reduction of everybody to the same uniform level.

Of course, I'm exaggerating. It wouldn't go quite that far, but it would go in that direction. And it is that perception that leads people to adopt what at first seem like inconsistent values. Look, for example, at the obvious immediate practical case of illegal Mexican immigration. Now, that Mexican immigration over the border is a good thing. It's a good thing for the illegal immigrants. It's a good thing for the United States. It's a good thing for the citizens of the country. But it's only good so long as it's illegal.

That's an interesting paradox to think about. Make it legal, and it's no good. Why? Because as long as it's illegal the people who come in do not qualify for welfare, they don't qualify for Social Security, they don't qualify for all the other myriads of benefits that we pour out from our left pocket into our right pocket. And so as long as they don't qualify, they migrate to jobs. They take jobs that most residents of this country are unwilling to take. They provide employers with workers of a kind they cannot get. They’re hard workers or good workers and they are clearly better off. If you ever want to know what people prefer, the surest sign is how they vote with their feet. Then there is no doubt how the Braceros vote. They vote to cross the border with their feet, on their feet, or in any other way they can, by the thousands and perhaps millions for all I know.

This illegal immigration is fascinating because it shows not only the main point I'm trying to bring out now, how interconnected are the various aspects of freedom, how interconnected is the problem of governmental arrangements for welfare and governmental arrangements for immigration and other things. But it shows a very different point that's kind of a digression, and that is how bad laws make socially advantageous acts illegal, and therefore leads to an undermining of morality in general. This is an obvious example. So long as the migration from Mexico is illegal, it's socially advantageous. It's doing everybody good.

But there are many, many other examples. The standard example of economists, of course, is tariffs or price controls. If you have tariffs, smuggling is performing a socially virtuous and valuable act. And so, you have smugglers who are now criminals. But they are people who are doing something that is good for everybody. The effect of this again, you can go on and on, price control and wage control has exactly the same effect, and so on down the line. If you have bad laws, you create a situation in which it is socially virtuous for people to break them, and this, in turn, breaks down respect for laws in general and plays a not negligible factor, in my opinion, in the decline in the attitude toward law, obedience, and morality in recent decades.

But let me go back to my main theme because I want to show how important these things are by a very simple and personal illustration. If the United States in the 1890s had had the laws that we now have, the laws supposedly to protect the worker, supposedly to protect the poor, if I existed at all today, I would be a citizen of the Soviet Union. That's not a prospect I would have relished. But my parents immigrated here in the 1890s. They were in their teens. My mother was 14 and my father was 16 or 17. They were able to immigrate here. Why? Not merely because we had free immigration, but also, for example, because we had no minimum wage laws. Had there been minimum wage laws, there would have been no jobs for them to take. Minimum wage laws, like so many of these other interferences, though enacted in the name of helping the poor, in fact, deny the very poorest opportunity.

And you can go down the line. There would be no entrepreneurs willing to provide employment under the only kinds of conditions and with the only kind of jobs that they were qualified for. Now, of course, it's a very hypothetical thing because if they couldn't have emigrated to the US, they might not have met over in Carpatho, Ruthenia where they came from. And if they had met in Carpatho, Ruthenia, they might not have gotten married and if they had gotten married they might not have conceived me, and I had been conceived, and you can go on with all the rest of the ifs. But had I survived, that particular area which was at that time part of Austro-Hungary, later of Czechoslovakia, is now part of the Soviet Union.

Can we get back on what what I regard as the right track, or have we been through a golden age? You know, I've always been fascinated by the story of golden ages in history. The fascinating thing about them is how brief they are. If you go back to the golden age of the 5th century BC in Greece, or you go back to the golden age in Rome, or go back to the several Elizabethan golden ages, or to the Renaissance. In each case, you have the same kind of phenomenon, a tremendous efflorescence, of flowering, of culture, of art, of industry, of architecture, of what-not, for about 75, 100, 125, a 150 years, and then somehow or other it all disappears. It's the same people, same Peloponnesian Peninsula, same land that was there before the golden age came, and after the golden age disappears. Have we been going through such a process? Was the 19th and first half of the 20th century our golden age? Are we on the way down? Or is there still a possibility of our being able to resume and have a renewed, a second, a repeated golden age?

We have many great assets. We have the asset of great wealth accumulated as a result of 200 years of a large degree of freedom. We have enormous diversity in our population. We have great springs of initiative. And we have another feature that was brought that I can best bring out by referring to a crack that our chairman, George Stigler, made some 30 years ago. Shortly after the war, he and I, and as it happens, a third person in this auditorium, traveled together to Europe to attend a meeting in Switzerland. It was our first time in Europe, and we spent two or three days in England and London, and two or three days in Paris, and then, you know, George is quick in learning, and as we left Paris, George remarked, I've discovered the fundamental difference between the English, the French, and the Americans. I should say we have been very much impressed in Britain by the extent to which everybody was… England was being strangled by the law obedience of its people, and queues were everywhere and so on, and we were impressed in France by how rampant the black market was. And so George's conclusion was, he said, you know, the fundamental difference is this. The English obey all laws, good, bad, or indifferent; the French obey no laws good, bad, or indifferent; the Americans obey the good laws.

Well, there's a very important element of truth in that because there probably is no more fundamental defense against tyranny than the ingenuity of the people in finding ways around laws that they don't agree with. Our masters found that out when they tried to prevent people from drinking hard liquor, and the American people demonstrated their capacity. That is really an enormous source of strength, and it is, in fact, I must say, my own main source of optimism.

But we also have great liabilities in trying to restore a new golden age. We already have gone very far in the direction of restricting our freedom. I need not go into all the details, but all of you are aware of the many ways in which you and I are not free to control our own lives in accordance with our own values. And there is a tremendous tyranny of the status quo. Each one of us will be very, very negative about the restrictions on freedom, except for those that benefit us.

Now, that's a different story. It's far easier to get a law into effect than to repeal it, as we've all found out, because you always establish interests, vested interests, which are very hard for any of us to get back. So, it's not by any means an easy task, but I think, and this is what I really want to talk mostly about today. To get back on the track, we need an understanding of the real nature of freedom, economic and political, and the interrelationship between the two. We need really to have a greater understanding than these general comments I have so far given, of the kind of system, the kind of principles that enabled us to to get this great achievement of the past 200 years. We need to understand how it is that a free market works to enable millions of people to cooperate peacefully together.

I know no better way to bring this out then by a very simple example that I owe to an old friend of mine, Leonard Reed, who once wrote a little article called, “I, Pencil.” This is the only prop I have for this TV show. As you can see, it's a straight plain yellow pencil. Said Leonard Reed in his article, you know, it's a funny thing, there's nobody in the world who knows how to make a pencil. Now that seems like a silly thing to say, isn't it? This is just the most obvious thing. It's only a piece of wood with something black in the middle and the little red tip at the end. What do you mean nobody knows how to make a pencil?

Well, suppose you were to start to set out to make a pencil. First of all, you have to get some wood, don't you? Where do you get the wood? You have to go to the Pacific Northwest probably and cut down some trees. How do you cut down some trees? You have to have some saws to cut it with. Where do you get the saws? You have to have some steel. Where do you get the steel? You have to have a steel mill. In order to have the steel mill, you have to get the iron ore, and you can add all the rest. So in order to know how to make a pencil, you would have to know everything there is to know about how to start from iron ore and coal, and get iron, and convert it into saws and cut down trees, but that's only the beginning. This black stuff in the middle that we call lead isn't lead. It's graphite, I think, I'm not absolutely sure, and I am told it comes from some mines in South America. So, in order to get that black stuff in between, you would have to take a trip down to South America and know all about how to extract graphite from the mines in South America. Now, this little red tip at the top, that's rubber. Where does it come from? Well, a major source of natural rubber is Malaya, that's quite another distance, and I don't know how many of you know that the rubber tree was not native to Malaysia. It was originally imported into Malaysia by private enterprises trying to make some money, and they transplanted it from somewhere in South America. I think it was Brazil, but I don't guarantee that. And they brought it over into Malaysia and established the plantations there and got this rubber.

So somehow or other, in order to make a pencil, you'd have to know about the rubber. Now there's a little brass tip around here, and I've run out of my own technological knowledge. I don't have the slightest idea where that comes from, so there are probably people in the audience who could tell us. Nobody knows how to make a pencil but the miracle of this pencil isn't that nobody knows how to make it. The miracle of the pencil is how did it get made? Who told that fellow over in Malaysia to tap his tree and send a little bit of rubber over here to put at the end of this pencil so I could have a pencil in my hand? What's happened? What is it that has enabled this little elementary transaction to take place? I'm not sure what the price of this thing is nowadays, these things change so fast. When I first started hearing about this story, it was a nickel pencil but that won't do anymore it's probably two for a quarter or 15¢ apiece. But what happens when I go down the store, and I put down a quarter and get two of these pencils?

I am trading with thousands of people all over the world, people in Washington state who are cutting down trees, people in South America, people over in Malaysia. I'm making a deal with them. I'm saying to them indirectly, I'll give you two minutes of talk for two of these pencils. Fact, I hope I've underpriced myself in that calculation. Now, how is that brought about? Is there some commissar sitting in some central office who is sending out orders to these people in Malaysia, to these people in South America, to the people in Washington? How is it that they are led to cooperate with one another? That's the miracle of the price system.

Because note, these thousands of people who have been led to engage in this simple transaction with me, not one of them has been forced to do it, nobody has had a gun to his head. They've all done it. Why? Because each one of them thinks he's better off in this transaction. And somehow or other, I've done it because I think I'm better off. Everybody has benefited. There's been no central direction. These people who have cooperated with one another don't speak the same language. They're people of all different religions. They may hate one another in every respect, but this hasn't prevented them somehow or other from being led to cooperate together. It hasn't prevented some kind of a wonderful machinery from bringing together these various components altogether into this little pencil. What is that machinery? What is it that has induced people to do this? How has it been brought about? That machinery is the price system.

That machinery is what the story is all about. That machinery is what enabled the United States to develop as it did, because it's this price system which has the great virtue that it doesn't require any central direction, it doesn't require any commissars, it doesn't require people to be able to talk the same language, it doesn't require people to be of the same religion. In fact, the beauty of the price system is that when you buy this pencil, you have no idea the religion of the people who went into it, whose work went into it. When you buy your daily bread, you don't know whether the wheat was grown by a black man or a white man, by a Chinaman or a Indian or, anybody else. And as a result, the price system enables you to have cooperation among millions of people peacefully cooperating on one little phase of their life. Well, each one goes about his own business in respect of everything else.

It works so well, it works so efficiently, that ordinarily we're not aware of it. It's like your car. It never occurs to you what a complicated business it is until 3 o'clock in the morning on a dark road, it stops functioning. And then you suddenly realize it's a complicated mechanism. And it's the same way with the price system. So long as it is working, so long as it's operating, so long as it's bringing people together, it doesn't even occur to you that it's this kind of a complicated mechanism. How is it that it achieves us bringing people together? The mechanism is that both parties to a transaction can benefit, provided it is voluntary and not coerced.

There's this terrible tendency, and most economic fallacies derive from that tendency, to think of everything as what the game theorists have come to call a zero-sum game, to think there's a fixed pie, and if I get more, you must get less. If somebody was able to make a fortune for himself, he must have done it by grinding under his heel the poor people because the pie is fixed and he takes a bigger part. The great insight behind the free market, the great insight of Adam Smith's great book, The Wealth of Nations, was that it is not a zero sum game, that it is possible for both people to a transaction to benefit, and that this insight can be used to organize people's activities over a very wide area.

It's very easy to see that principle operating if you think of two people, under any circumstances, making a voluntary deal. I'll trade my pen-knife for your roller skates. Clearly, that isn't a deal unless both people are better off. It's much harder to see how that same principle is involved in the far-flung transactions that went into making this pencil, and yet the same principles are there. The price system operates in this way because it doesn't require orders. It operates in this way because it can transmit information in a very efficient way without any person having to send an order.

What happens if you, or the rest of us, want to get some more pencils? Well, the people who are manufacturing pencils suddenly discover that they're making some money, and they say, we'd better make some more pencils. Nobody has told them about that. They've just discovered it down at the corner drugstore. And they, in turn, say, send out some orders to people who are producing the wood, to the people who are producing the rubber. The effect of this is to raise the prices a little all the way down the line for the particular items in demand, and that higher price becomes a signal to people all over the world that there's a greater demand, a greater desire for this particular object.

Now, the beautiful thing about that signal is that the information is transmitted to those in a very efficient way, because only the important item is transmitted. The people who are in the market for producing wood don't have to know why more wood is demanded, they don't have to know whether the demand for pencils has gone up because there have been 14,000 more government regulations that have to be filled filled out in pencil, or whether maybe the demand for pencils has gone up because the post office officers have said, if you address your letters in pencil, we'll only charge you 13¢ stamps. They don't have to know why there are more pencils or whether it's because there's a baby boom and more children are going to school and writing. All they have to know is that somebody is willing to pay a little bit more money for some more wood and some more graphite and some more rubber. That information is spread and the only people who have to know about it are the people who are in a position to provide the additional wood, or the additional graphite, or the additional rubber. So the information is transmitted economically and efficiently, and it's transmitted to those who need it from those who need it.

In the second place, the information combines with it an incentive to act on the basis of that information. It's no good sending out a message to people, “We need more wood but we're only going to pay you the same amount we did before.” You're not going to get anything out of it, well so you need more wood fine, that's the end of it. The beauty of the price system is that along with this information, and this is the second stage, goes an incentive to act on the basis of it, because the man who is selling wood, if the price has gone up a little, well, he figures he can make a little more money in that way, and so he has an incentive to act on it. And that incentive is there because his income is ultimately going to be determined by the prices of the things he sells…

[continued in Part 2]

Immigration road map should be, who is going to help us and contribute to us continuing to be the greatest country in the world. No use for letting criminals and terrorists in.

Bryan, perhaps you have seen the headlines about certain states offering housing benefits to immigrants that are not offered to citizens. What do you make of this? Is this policy affordable? I actually understand California's plan is not funded! What are citizens supposed to make of these policies?

It is absolutely common sense that you cannot have open immigration with government picking and choosing winner and losers and handing out benefits not earned by the immigrant, let alone by the citizenry. No nation can afford such a policy. And politically, policy that pits citizen against immigrant will lead to massive unrest and conflict.

Some of your readers, including myself, would appreciate you argued immigration policy (including the handling of illegal immigration) with respect to how policy actually exists in the US and Western Europe. Are those immigration policies working? Clearly, we are seeing tremendous government interference. Are you willing to concede that this government interference makes the Libertarian argument for immigration a hypothetical that does not exist in reality? Or do you believe there is some magic that will cause government to stop interfering?