[continued from Part 1; remember that immigration-related passages are in bold]

The price system can operate to coordinate the activities of millions of people around the world because it combines three functions: the function of transmitting information, of providing an incentive for people to act on the basis of that information, and last but not least, a mode for distributing the product of that activity. These three are enormously important, but it's very easy to try to separate them. Most great schemes for social reform come hoist on the attempt to separate them.

I remember once being at at a conference which brought together economists from the East and economists from the West, economists from behind the Iron Curtain, and economists from the West. And there was a brilliant economist from behind the Iron Curtain. This fellow had all by himself rediscovered Adam Smith. Well, that was a pretty brilliant thing to do. Adam Smith was a pretty brilliant fellow, but the one thing that stopped him, this was someone from Hungary as it happened, was that they kept trying to figure out how they could get the benefits of the first two functions of the price system without the benefit of the last, how you could get the benefits of the information and the incentive effects of the price system without also using it to distribute the income.

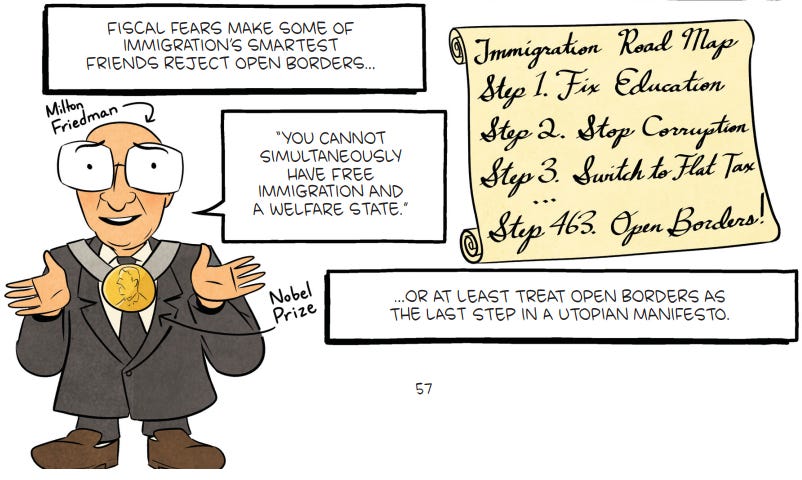

And you will see that I have come back full circle to my paradox about immigration. Because that's exactly why in the modern kind of a welfare state, free immigration is not really feasible, because in that kind of a state, we have gone too far in eliminating the function of the price system for distributing the income as well as providing information and incentives.

In any event, the main point I want to bring out is that this is the way in which the market system works. It's a system. People tend to think that you can only have a system if some human mind designs it, if some single person controls it, that it's otherwise disorganized, chaotic. That's the usual word, the chaos of the price system. But if you let your mind go over this simple example and see how you have organized these many people around the world, you will see that it is really a system, not simply chaos, and a system which has laws of its own, dynamics of its own.

The typical thing that we always say when we talk about organizing economic activity is to say that there are two ways of organizing economic activity: command, the method of the army, or voluntary exchange, the method of the market. That's really false as a practical matter. In practice, with any complicated modern society, it is simply impossible to organize it by command. There is no cybernetic system, there is no computing system powerful enough to enable somebody at the center, or however you decentralize it, through command, to control the last detailed activity of everybody along the line. You know that the standard way, one of the standard devices for labor disputes, is to throw the rule book at the employer, or as they sometimes say, to work according to rule. You cannot dispense with the separated knowledge and interest of the people at the bottom of the line.

And that's why, except in the simplest cases, and even in the simplest cases where all members of families, and the standard example that is ordinarily given about the simple command economy, is a family. It it used to be the father, it's now the mother who's in control. But if you, all of us have been in families, and you know you really can't organize a family by command. You have to do it by voluntary agreement.

I don't know how many of you have read Hedrick Smith's splendid book on The Russians, but he discusses the Russian economy. There's a case in which command has been followed, carried perhaps to its highest extent in any country in the world, in any society in the world. But, as he points out, mostly, Russia is really organized through voluntary exchange of one kind or another. As you all probably know, to go back to my first example of agriculture, something like 3% of the arable land in Soviet Union is in small private plots. The statistics are that something like a third of all the food of the country comes from that 3% of the arable land. I'm not saying it grows on it. I suspect it comes through it.

The Russians are not without their ingenuity and getting around systems too. But much more beyond that, Smith points out that if something goes wrong with your electric light fixture, the last thing you'll do in the world is to call a government organization for the repair and maintenance of light bulbs. You will instead find a moonlighting fella who will come around in the evening and, for a private side payment, fix your electricity. Otherwise, you'll be without electricity for, well, an indefinite length of time.

There is a flourishing voluntary exchange economy, but even more than that, within the factories, within the governmental arrangements, all the way down the line you have to rely on people using their own initiative. So that in fact, there is only one way in which any complicated society can be organized. But there is an enormous difference between a system in which that is permitted to be the dominant way and a system in which that way has to overcome the distorting influences of the commands.

What you have in every society is fundamentally the use of voluntary exchange at the bottom. But if it is accompanied by an excess of attempted command, the combination of the two is tyranny and misery. The command produces a tyranny. And the most that voluntary exchange fighting against those commands can do is to prevent the misery from being absolute. It at least relieves the misery a little and allows the system to operate.

Let me close by emphasizing that I've been discussing the role of the market in a free exchange, the role of freedom, economic freedom, and its connection with political, human, religious freedom. That the role of the market, this point I'm making about the market enabling you to separate the economic activities from the other activities, is what's essential to the maintenance of political and social freedom. But I am emphasizing that because I think that's what we need more of. I am not arguing that government does not have a role. Of course it does. I am not an anarchist, but I am persuaded that the problem of our society today is too much government, not too little.

Indeed, I am persuaded that government is failing to perform the functions which it alone can perform because we are trying to have it perform functions which it cannot perform. In Walter Lippmann's phrase, which I may say goes back to the 1920s, we are an over-governed society. I believe we can get back on the right track only as the public at large comes to recognize that the direction we have been going is a false direction, a direction that will lead us not where we want to be, but where we do not want to be, and that we can get back only on the right track by stopping and then reversing that trend.

Thank you.

[Question and Answer Period Begins. Questions in italics.]

And how would you reconcile your advocacy of open immigration with your support of a negative income tax, program which would have in effect a minimum income for every American?

It's a very good question because, of course, in that form, they are incompatible. I agree. And that leads back to the question of the negative income tax. If you are starting from scratch, if you did not have any welfare programs at all, if you were back in the situation when you did have open immigration, I am very dubious that I would be in favor of a negative income tax. I am not in favor of a negative income tax as a good thing in and of itself. I am in favor of it as superior to the present welfare mess, and as a way in which we can possibly move from where we are now to a situation under which you could have open immigration.

I agree, today you could not have open immigration. You could not have open immigration because you do have essentially a guaranteed minimum income, whatever you call it. You have a guaranteed minimum income in the form of a large number of very varied and different kinds of programs, whether you include food stamps, Aid to Dependent Children, Social Security, SSI, and so on. They are a mess. They mean that people who are in the same position may get very different benefits depending on how many programs they can qualify for. It means that many people have a strong incentive not to work, and that by working, they only make themselves worse off and so on down the line.

At the same time, you cannot abolish all those programs overnight. You have some millions of people whom you have led to become dependent on those programs. If you hadn't had the programs, they wouldn't have been dependent, but there they are now. You cannot simply turn your back and say we're going to pull out the rug from under you. You have to have some kind of a transitional device, and I have always viewed the negative income tax as a way in which you could have a program that would be far superior to the present structure, in that it would help people who are poor because they're poor. It would help them in a way which would retain an incentive for them to work, and at the same time, over time, you could gradually get out of the business by holding the amounts relatively steady, while the economy grew and grew. And then, if you started in that direction, maybe you could eventually come to a position where it would be possible to have free immigration. Thank you.

Mr. Friedman, how much government intervention do you think is necessary to prevent the rise of monopoly and oligopoly under the free enterprise system, or would it take care of itself?

Well, I believe if you examine the sources of monopoly and oligopoly, you will find that almost all those sources are government intervention.

I think the situation is almost precisely the reverse. Let me put it in a very simple way. Suppose I were to ask this audience my favorite question along these lines, you have one law you can pass. Its only purpose is to reduce the extent of monopoly. That's its only purpose. You have one law. What law would be most effective in achieving that end? What law would you pass? I don't mean any gimmicks, you know, it's not going to be something in which you can have a law with 4,000 different parts. I'm not asking a very complicated question. What would you do?

Limit the size of the market that they could…

Well, that's one proposal. The limitist proposal. But you will agree with me, I'm sure, immediately that mine is a much better one, and that's free trade. Eliminate all tariffs and all restrictions on foreign trade, and you enable the world to come in as competition to prevent domestic monopoly. Wouldn't that do a great deal more good in preventing monopoly than would a limit on the size of enterprises, with much less restriction in human freedom?

Now, if you ask yourself ask yourself where do monopolies come from? In the United States, the most important and the strongest monopolies are unquestionably those that derive from governmental privilege. The monopoly of a TV license granted by the government at a zero price, that's a source of monopoly privilege. It also has been a source of wealth for some notable Americans. The grant of a tariff protection. Would the steel industry in the United States have any kind of monopoly or oligopoly position? If it weren't able to get government to impose impose restrictions on imports of foreign items and so on. Trade union monopolies, they get their strength and their support from Davis-Bacon Act, Walsh-Healey Act, other governmental measures that interfere with competition by others.

It's very hard. In fact, I have tried to consider, and George Stigler is a greater authority on this than I, so we maybe we ought to get him in to add to this. What private monopolies are there that have been able to maintain themselves over any long period of time without government assistance? And I have myself only been able to construct two.

One is an international one, the De Beers Diamond monopoly. It really isn't… I don't understand it, maybe George can tell us the answer, but it has been successful over a very long period. And the second was the New York Stock Exchange. Not more recently because since 1934, it's had the help of the SEC, but before 1934 from about the civil war to 1934, so far as I know it had no government support and yet it did maintain an effective monopoly.

But almost every other case, you have temporary monopolies develop and if the government doesn't come in to shore them up, they fall to pieces. The railroads became a monopoly only because they were able to get the Interstate Commerce Commission established. Trucking is a monopoly because the ICC keeps out competitors, and you can go down the line and find that one hypothetical monopoly case after another derives from governmental assistance and support. So I think the answer to your question, and you and I have the same objective here, is less government intervention, not more. Thank you.

I very much enjoyed your example about the pencil, but it raised a very serious question in my mind. It's that there's only so many trees to get that pencil from and there's only so much steel to be mined. Now how would a free enterprise system go about creating more trees? They only grow so fast. Or steel can only be discovered as…

That's a very, very good question. I remember once, about 15 or 18 years ago, I was on a private farm in which they were planting a crop which was gonna have a yield a 100 years from date. That crop was trees. It was a farm in Sweden, which was a tree farm, and they were planting trees. And they were doing it for private enterprise purposes. And now you will say to me, “How in the world can the market do that? There's nobody who's gonna live 100 years.” But if I plant a tree and it's one year old, well, its value will be a little higher than if it isn't there at all. If it's two years old, it'll be worth still more. If it's three years old, it'll be still worth still more. So, I, as an individual planting those trees, don't have to look to my length of life. I am creating value every year as those trees mature, and the closer they come to the time when they can be used for the purpose of making pencils, the greater the value they have. So I have a strong incentive to invest in those trees.

Now, when it comes to the time when I want to use that money that I've been saving and accumulating, I say money, I mean those resources, those physical assets, I will sell it to somebody else. Maybe he'll hold it another five years. In the same way, if you go back to the tree example, if you own a tree farm, how fast does it pay you to cut it? Does it really pay you to cut it down to the ground right now? Not at all. That depends on what's going to happen to the price of wood in the future. See, the price system is a very subtle and sophisticated thing, because it also gives you information about whether you should save things for the future. If it looks as if something is going to be very scarce, then it will be to your incentive to hold on to it, and not to let it go. And that will drive up its price immediately, and that will give people an incentive today to consume less of it.

Take trees. The matter the fact is that the total amount of trees is not finite. The total amount of trees is infinite because you can plant it, you can grow it, you can harvest it. And unless I am mistaken, there are more trees being harvested today than there were 50 or 75 or 100 years ago. The volume of wood production has gone up, not down. It's really a mistake to suppose that you've got a finite…

You see, again, if you'll pardon me, you're involved in the same mistake I mentioned before, the fixed pie idea, the zero sum game idea. There isn't a finite amount of trees out there. How many trees it will pay people to grow depends on what they expect the future demand for trees to be. If somebody discovers some way of having a substitute for trees that are half as expensive, then the forest will disappear for that purpose. If, on the other hand, trees become more valuable, well, then they will be planted and grown. Same thing with steel, with iron ore, and with other things. People are really, oh, you know, this kind of nonsense that you hear from the Club of Rome and similar engineers about finite physical resources setting a limit to economic possibilities, is really a bunch of nonsense. Most of the value of our product, most of our output, doesn't consist of raw materials at all. The total cost of the raw materials in our national income is under 10% of the total national income. Most of that value comes from here, not from there. Okay. Thank you.

In your opening comments, sir, you made some, some reference to ethnic separation and the melting pot. Well, it seems that you spoke in disparaging tones as to ethnic solidarity. Would you please comment on that?

Sure. I'll be glad to. I believe it's highly desirable for people to be able to pursue their own values, to have whatever ethnic values they want, provided they do it voluntarily, and do not interfere with the freedom of others to do it also. We want a society of variety and diversity. We want a society in which people can celebrate their own special ethnic backgrounds, but that's a very different thing from a society which somehow takes ethnic characteristics as a criterion for preference or lack of preference, for a society which moves away from the doctrine of color-blindness to the doctrine of so-called affirmative action.

That's the problem. The problem is… You see, this is one component of a very much broader problem. You cannot achieve, in general, good ends by bad means. And the end, the desire to correct past discrimination, the desire to improve the conditions of people, to enable people of all colors, creeds, backgrounds to have a more even story, is an admirable end. But that end is corrupted when you use the wrong methods to achieve it. And the methods of force and coercion are, in my opinion, the wrong method that do corrupt it.

Don't you think it's through ethnic solidarity that many minority groups were able to make advances in the American society?

Not in the slightest. If you look at the way in which ethnic minorities made advances, it was not through ethnic solidarity. It was through the free market. You can take any group you want to, whether you take, for example, the group, obviously, I've been closest to are the Jews. How did the Jews make their way? Only in the competitive areas of the American economy. How did the blacks make their way? Only primarily in the competitive areas. The laws what have been the greatest hindrance… Where are the areas where the blacks have been most hampered? In those areas where government has supposedly been doing something for them. There is no area in American life in which the blacks are more disadvantaged than the kind of schooling they can get. Why? Because it's provided by the government. The minimum wage laws are supposed to help the poor, to help the disadvantaged. They are the most anti-Negro laws on the books. Why do we have unemployment rates of 40 to 50 to 60 percent for black teenagers? Because the law says it is illegal for an employer to hire them at a wage, which corresponds to their productivity and to their worth. That he can only hire him if he's willing to pay him charity. It's a law that he must discriminate against people with low skills.

First, we give them lousy government school, so they have no skills, and then we make it impossible for them to get job training, training on the job, by saying to employers, it's illegal for you to hire them. And that's why, if you look at the record, you know, this is a recent phenomenon. If you go back to the immediate post war period, before the minimum wage was binding, the unemployment rate for black teenagers and white teenagers is roughly the same. Today, it's 2 or 3 times as high for black teenagers. If you go back to that period, the fraction of black teenagers in the labor force was higher than of white teenagers. Today, it's lower. Why? That's almost entirely a result of the minimum wage law, plus a very inferior form of governmental education.

Again, what has been the source and the focus of racial discrimination? The craft trade unions. Why? Because they have gotten governmental monopoly powers essentially that have enabled them to keep people out. What is the activity, the commercial activity, which has had the greatest degree of exclusiveness of blacks and, in this case, also of Jews? No doubt, for decades, it was banking. Why? Because banks had a franchise from the government. You will search long and hard before you find any minority that has effectively had its rights protected or its opportunities expanded by government intervention in its behalf. Try to find an example.

But, isn't it often through solidarity of a group that they are able to fight government intervention such as in, or any group's intervention in their rights such as, overthrowing quota systems?

Well, let me see. Let me separate issues. I'm not I have no quarrel to ethnic solidarity, of course, in the sense of helping one another, and no doubt, by a feeling of identification and of assisting one another. They have helped one another, of course, but the particular aspect you're taking is to say that one evil raises another evil. I agree with you, that once you start on the route, where you turn to government to control the conditions of entry, then people who wanna fight against bad government discriminations have no other choice but to go through the same political mechanism. So I agree with you that they have. But that's as a lesser evil, not as a positive good. Thank you.

Dr. Friedman, in relation to your statements as far as Mexican immigration go, I'd like to make the following comment. And that is that, it seems to me that Mexican immigrants have a choice between, on one hand, staying in Mexico and getting what life they can, which to me seems like trying to evade starvation as long as possible, or crossing the river and then taking the job that they have available. And what I'm wondering is, is this choice a choice at all? And is it not equivalent to this gun against the head that you were talking about as absent from the free…

Who's holding the gun?

The capitalists in Southern California who own the…

On the contrary, in your image, it would be the Mexicans who are holding the gun. Well, they deny them the opportunity in Mexico.

There aren't enough capitalists in Mexico, as opposed to… Not enough jobs available.

Obviously, they have two bad choices. That doesn't mean that one isn't better than the other.

Well, yeah, I agree.

And you must distinguish sharply between somebody giving you a choice, which is not a very satisfactory one, and somebody imposing something on you. Nobody is holding a gun to the head of these people and saying they should come to California. They are coming there because they believe they can have a better life for themselves and their children.

They can have a better one. Yes. But is it a life, or as you said yourself, no American would would like to do these jobs.

No, it's not that no American would like to. Many Americans would be perfectly willing to if that were their only alternative, but the Americans have better opportunities. Fine. How did the Americans get to have those opportunities?

By being American citizens? Is that the point you said?

No. No. By initially going through stages similar to that which the Mexicans are going through. They didn't, you know, people don't come full-blown into the world. The nations don't come full-blown into the world with skills and capital and so on. That all has to be derived through a long historical process.

I agree.

Then what's the alternative? If you say, well, we're willing to have the Mexicans in only if they can be supported at the level at which the Americans are supported, then you're condemning them to stay in Mexico.

But isn't it true…

So don't hurt them in order to help them.

Isn't it true that the wine growers in Southern California would prefer to have these Mexicans working at the rate they are working at than they are to have Americans come in and demand higher wages because of the alternatives they have?

They would prefer to pay lower wages rather than higher wages. You'd like to pay lower prices for the things you buy rather than higher prices. Of course, that's the whole system. That's exactly the system and if you say to the Mexicans, you may not offer to work for lower wages, then you're denying them the only weapon they have.

But aren't you also…

That's why equal pay for equal work laws are a source of apartheid. You know, the basic source of apartheid in South Africa was the insistence by trade unions on equal pay for equal work. The women who go around today urging equal pay for equal work are being anti-feminist. They don't intend to be, but that is the effect of their policy. Because if there is any activity, in which for any reason, a male is preferable to a female, or vice versa, the only weapon the less productive sex has is to offer to work for less. And if you deny them that opportunity, you're assuring yourself that you're gonna have all-male jobs, or all-female jobs, or all-white jobs, or all-black jobs.

But aren't you also condemning them to stay that way?

Not at all. Not at all. The typical course, if you go back to American history, by taking these low paid jobs, a great many people, not all, but a great many people, were able to develop skills and activities, accumulate a little skill, a little capital, a little knowledge, improve their lot, become advance in the stage, get to a higher level of productivity, and get a higher income. That's been the typical way up the ladder for most of the people who came in here. It was a way up the ladder for my parents, for your parents, or grandparents, or great-grandparents. I don't know which. And that's the way in which, unfortunately, there's no way in which you can immediately propel people to the top of the ladder. Okay. Thank you very much. Thank you.

You spoke a few times. You mentioned distribution of wealth.

Sure.

But most of what I've heard you talking about has been about distribution of income, rather than about the distribution of wealth.

Yes.

Now, you wouldn't argue, at least I hope you wouldn't, that the person in, let's say…

Okay. Sure.

Let's say, India is genetically inferior, say, to the person in America, is rather through the purely arbitrary circumstance of birth that he is in a country with a less-developed economy and or in a family that doesn't have as large a share of the capital. And that's not something that he is to blame for.

Oh, I'm not blaming anybody.

Even if the free market system equitably works and everyone progresses an equal amount, that person who started out with a lesser share of the capital is still going to end up with a lesser share of the capital.

That's right.

And there's nothing in the free market system that's going to enable him to make up for what was a purely arbitrary deficit in the first place. And given that the kind of people who become successful capitalists do not become that way by giving away their wealth voluntarily, isn't it necessary to forcibly redistribute wealth before you can begin to operate under a capitalist system?

No, it is not. Now, but let's examine this argument because, of course, it's true. There's no justice in the distribution of income or wealth. I never would argue there is. Those who are wealthy don't deserve to be wealthy any more than those who are poor deserve to be poor. It's pure accident. And we might, but if you start to look at things that way, you're gonna go down the wrong line because you're gonna get back into this kind of a situation of destroying the good things, destroying what is possible in the search of an impossible ideal. The only way in which you can redistribute effectively the wealth is by destroying the incentives to have wealth. And the question is, what is the way, what is a system which will offer those people who are so unlucky as to be born without good positions, what is the system which will offer them the greatest opportunity?

Well, one possible way of redistributing the wealth without affecting the incentives to earn as much income as possible, is simply to have a 100% inheritance tax.

But…

Because that won't affect the incentives. It's only after the person's dead, anyway.

I beg your pardon. You're too, I'm afraid, I don't know the family you come from. I don't, but as you grow up, you will discover that this is really a family society and not an individual society. We tend to talk about an individualist society, but it really isn't. It's a family society. And the greatest incentives of all, the incentives that have really driven people on, have largely been the incentives of family creation, a family of pursuing, of establishing their families on a decent system. What is the effect of a 100% inheritance tax? The percent of a 100% inheritance tax is to encourage people to dissipate their wealth in high living.

Why can't they… What’s the harm in that?

The harm in that is, where do you get the factories? Where do you get the machines? Where do you get the capital investment? Where do you get the incentive to improve technology, if what you're doing is to establish a society in which the incentive is for people who, if they have by accident accumulated some wealth, to waste it in frivolous entertainment. You know, the thing that is amazing is that people don't really recognize the extent to which the market system has in fact encouraged people and enabled people to work hard and sacrifice in what, I must confess, I often regard as an irrational way for the benefit of their children.

One of the most curious things to me in observation is that almost all people value the utility which their children will get from consumption higher than they value their own. Here are parents who have every reason to expect that their children will have a higher income than they ever had and they scrimp and save in order to be able to leave something for their children. I think you are sort of like a bull in a china shop. If you talk about the limit, a 100% inheritance tax having no incentive effects, it would destroy a continuing society. It would destroy a society…

Well, you're saying…

…in which there are links from one generation to the next. Okay.

Mr. Friedman, referring to the statements that you made about women who advocate equal pay for equal work.

Gee, I thought I'd get a rise out of that. Sooner or later. Delighted to have it. Yes. Okay.

I just would like know if you're insinuating or perhaps, you know, point blankly saying that, women and other minorities' skills are inferior to those of those now holding those jobs, and that they need to go through a period where their skills need to be improved and therefore deserve to be paid less?

No. I don't think desert has anything to do with it. I'm not first of all, I think desert is an impossible thing to decide. Who deserves what? Nobody deserves anything. Thank God, we don't get what we deserve. But I'm not saying that at all. I'm saying a very different thing. I'm saying that the actual effect of requiring equal pay for equal work will be to harm women. If women's skills are higher than men's in a particular job and are recognized to be higher, the law does no good because then they will be able to compete away and can get the same income. If their skills are less for whatever reason, maybe it isn't because it's their sex, maybe it's because they were out of the labor force, maybe it's for other reasons, and you say the only way you can hire them is by paying the same wage, then you're denying them the only weapon they have to fight with. If the unwillingness of the men to hire them is because the men are sexist, are what's the phrase, racist, sexist pigs, or whatever. If that's the only reason they want to hire them, nonetheless, if you want to make it costly to them to exercise their prejudice, if you say to them, you have to pay the same wage no matter whether you hire women or men, then here's mister sexist pig. It doesn't cost him anything to hire men instead of women. However, if the women are free to compete and to say, well, now look, I'll offer my work for less, then he can only hire men if he bears a cost. If the women are really good as a man, then he's paying a price for discriminating. And what you are doing, not intentionally, but by misunderstanding, when you try to get equal pay for equal work laws, is reducing to zero the cost imposed on people who are discriminating for irrelevant reasons, and I would like to see a cost imposed on them. I'm on your side, but you're not. Thank you.

1) Unskilled workers may not be net positives in the first generation of immigrants, but they are hardly a majority of all immigrants - making immigrants as a whole (even those called “illegal”) a net positive. 2) Most visa infractions are by people who cross borders on planes, suggesting some sort of sophistication above border crossing migrants (for which there is a stronger moral argument). 3) Welfare state is abused more by natives than migrants.

I think Milton got this one wrong on immigration but right on welfare state.

Immigration is not about chasing a welfare state - it’s about opportunity. Immigration existed bf welfare state, why? Because immigration is about opportunity not free riding. As mentioned, given the overall net benefit to society and the potential benefit from second generation and assimilated low skill migrants - there is only upside to open borders (with checks for violent criminals).