Friedman Contra Open Borders (1978): A Line-by-Line Critique

Nobody's perfect, not even peak Milton Friedman

Friedman’s position on immigration in 1978 was notably more thoughtful than his position in 1999. 21 years of aging take their toll on the best of us. But at his peak, Friedman’s analysis of immigration was still uneven at best, leading him to hastily reject the greatest of all possible free-market reforms: open borders. Here’s my line-by-line critique of everything Friedman said about immigration back in 1978.

To be clear, Friedman is in blockquotes, his questioners are in blockquotes with italics, and I’m in normal text.

That's the most dramatic and obvious exemplification of this miracle that was America, but you can look at it in a more general way. Here over the 19th century, into the 20th century, this country welcomed millions and millions of immigrants. I suspect that most of the people in this room today are descendants, 1st generation descendants, as I am, 2nd or 3rd generation descendants, then most of the people in this room are descendants of those immigrants who came to the United States from foreign lands with empty hands. I suppose there is a substantial exception because I see a good number of you who are citizens of other countries, and you are not descendants of those, but you are the modern way that we ought to be welcoming as immigrants in the same tradition which enabled the rest of us to get here.

So far, so good.

You had a flood of immigrants, of millions of them coming to this country. What brought them here? It was a hope of a better life for themselves and their children. And in the main, they succeeded.

A serious understatement. International wage gaps were smaller in the 19th-century than they are today, but they were still enormous. And as usual, any large increase in productivity ends up being widely-shared.

It is hard to find any century in history in which so large a number of people experienced so great an improvement in the conditions of their life, in the opportunities open to them, as the period of the 19th early 20th century.

I agree with the spirit of this claim, but the post-war period was probably even better, and thanks to Deng’s free-market reforms in China, the post-1978 period has probably been the highest-growth period of all.

What was the source of this great achievement? Well, as has already been implicit in what I've said, the first and most important source was a set of values, a set of institutions that left people free to pursue their own interests according to their own lights.

OK.

What is the basic problem of the United States today? The problem is that we are threatening to strangle this promise by government interference. Let me take as one example the feature I've already spoken of, free immigration. I have always been amused by a kind of a paradox. Suppose you go around and ask people, the United States, as you know, before 1914 had completely free immigration. Anybody could get on a boat and come to these shores, and if he landed on Ellis Island, he was an immigrant. Was that a good thing or a bad thing? You will find hardly a soul who will say it was a bad thing. Almost everybody will say it was a good thing, but then I suppose I say to the same people, but now what about today, do you think we should have free immigration? Oh no, they'll say, we couldn't possibly have free immigration today. Why, that would flood us with immigrants from India, and God knows where, we'd be driven down to a bare subsistence level.

But “immigrants will drive us down to a bare subsistence level” was also a popular view before 1914! The real pattern is that Americans have long been favorable toward past immigration, but pessimistic about current and future immigration.

What's the difference? How can people be so inconsistent? Why is it that free immigration was a good thing before 1914 and free immigration is a bad thing today? Well, there's a sense in which that answer is right. There's a sense in which free immigration in the same sense as we had it before 1914 is not possible today.

Notice Friedman’s lazy leap from “would be worse than in 1914” to “is not possible.”

Why not? Because it is one thing to have free immigration to jobs. It is another thing to have free immigration to welfare, and you cannot have both if you have a welfare state, if you have a state in which every resident is promised a certain minimum level of income or a minimum level of subsistence regardless of whether he works or not, produces it or not, well, then it really is an impossible thing.

Again, note Friedman’s childish hyperbole. “Ill-advised for native taxpayers”? Maybe. “Impossible”? Absurd.

Even if you tone down the hyperbole, Friedman should be weighing the direct economic gains of raising immigrant workers’ productivity against the net fiscal burden of the welfare state. The welfare state moderately depresses the former, but since immigrants still have high labor force participation, most of the direct economic gains remain. What about the net fiscal burden? That depends on a host of factors that Friedman barely mentions, starting with: eligibility conditions and the height of the minimum. If the minimum is still well below immigrants’ expected earnings, or if immigrants lose eligibility for most benefits in a matter of months, the net fiscal burden of even low-skilled immigrants can easily be negative despite the welfare state.

To be fair, back in 1978 the analysis of net fiscal burdens was in its infancy. But that’s no excuse for assuming the worst, as Friedman does. And if you look at the least-bad modern estimates of the National Academy of Sciences, Friedman was way off.

If you have free immigration in the way in which we had it before 1914, everybody benefited.

More night-and-day hyperbole. Before 1914, taxpayers were already shouldering one of the largest components of immigration’s fiscal burden: public education.

The people who were here benefited. The people who came benefited because nobody would come unless he or his family thought he would do better here than he would elsewhere. And the new immigrants provided additional resources, provided additional possibilities for the people already here, so everybody can mutually benefit.

Friedman is so focused on arguing that immigration has gotten worse since 1914 that he overlooks a major way that immigration has gotten better. Namely: Global incomes are much more unequal than they used to be. As a result, the direct economic benefits of immigration are vastly larger than they used to be. In 1914, low-skilled Europeans might have only doubled their productivity by moving to America. Today, the typical low-skilled immigrant easily multiplies his productivity by a factor of five.

But on the other hand, if you come under circumstances where each person is entitled to a pro-rated share of the pot, to take the extreme example, or even to a low level of the pot, then the effect of that situation is that free immigration would mean a reduction of everybody to the same uniform level.

Of course, I'm exaggerating. It wouldn't go quite that far, but it would go in that direction.

Finally, we see Friedman working near his ordinary level of intellectual diligence. But his qualifier is hardly mere boilerplate. If all immigrants go on welfare for life, immigration has bad overall effects. If things merely “go in that direction,” free immigration could easily remain awesome on balance.

And it is that perception that leads people to adopt what at first seem like inconsistent values. Look, for example, at the obvious immediate practical case of illegal Mexican immigration. Now, that Mexican immigration over the border is a good thing. It's a good thing for the illegal immigrants. It's a good thing for the United States. It's a good thing for the citizens of the country.

That’s my Friedman.

But it's only good so long as it's illegal.

That's an interesting paradox to think about. Make it legal, and it's no good. Why? Because as long as it's illegal the people who come in do not qualify for welfare, they don't qualify for social security, they don't qualify for all the other myriads of benefits that we pour out from our left pocket into our right pocket. And so as long as they don't qualify, they migrate to jobs. They take jobs that, most residents of this country are unwilling to take. They provide employers with workers of a kind they cannot get. They’re hard workers or good workers and they are clearly better off.

Another lazy leap. Yes, illegal immigrants cost taxpayers a lot less (though that number will still be high if their kids go to public school). But illegal workers also tend to get stuck in low-skilled jobs where immigration enforcement is low. Legalization allows immigrants to make full use of their talents in the labor market, to the betterment of themselves, natives, and humanity. Net effect? Unclear at best. Sure, the empirical evidence was thin in 1978, but Friedman should at least have kept an open mind.

Indeed, the most logical immigration policy for Friedman to embrace is “free immigration without welfare eligibility.” He never mentions this possibility in 1978. When asked about this idea in 1999, he bizarrely claims to have never considered it, then frets:

I don't think it's desirable to have two classes of citizens in a society. We want a free society. We want a society in which every individual is treated as an end to themselves.

We don't want a society in which some people are in there under under blue conditions. Others are in there under red conditions. Others are in there under black conditions. We want a free society.

So he’s OK with illegal immigrants, but not legal immigrants who are ineligible for welfare? Isn’t the former a much more egregious case of having “two classes of citizens in a society”?! Isn’t a society where you can legally work but not collect welfare “freer” than one where you can’t legally work at all?!

OK, back to 1978:

If you ever want to know what people prefer, the surest sign is how they vote with their feet. Then there is no doubt how the Braceros vote. They vote to cross the border with their feet, on their feet, or in any other way they can, by the thousands and perhaps millions for all I know.

Indeed.

This illegal immigration is fascinating because it shows not only the main point I'm trying to bring out now, how interconnected are the various aspects of freedom, how interconnected is the problem of governmental arrangements for welfare and governmental arrangements for immigration and other things.

Sure. But Friedman should also have noticed that strict immigration restrictions preceded the New Deal. Which is a strong sign that the root causes of immigration restrictions are economic illiteracy and xenophobia, not the rise of the welfare state. Which in turn should have made him wonder if the welfare state actually turns free immigration from a great good into a grave evil. Because it sounds more like an excuse for what most voters wanted to do regardless of the consequences.

But it shows a very different point that's kind of a digression, and that is how bad laws make socially advantageous acts illegal, and therefore leads to an undermining of morality in general. This is an obvious example. So long as the migration from Mexico is illegal, it's socially advantageous. It's doing everybody good.

More childish hyperbole. With or without the welfare state, all immigration hurts someone. Why? Because all progress hurts someone! Even if you solemnly vow to “compensate all the losers,” you won’t, because it’s too damn hard.

That said, at least the Friedman of 1978, unlike the Friedman of 1999, put liberty above legalism. I’m still shell-shocked by the fact that Friedman 1999 opposed guest worker visas because “I don't think it's desirable to have two classes of citizens in a society.”

But let me go back to my main theme because I want to show how important these things are by a very simple and personal illustration. If the United States in the 1890s had had the laws that we now have, the laws supposedly to protect the worker, supposedly to protect the poor, if I existed at all today, I would be a citizen of the Soviet Union. That's not a prospect I would have relished.

Plausible, setting aside the non-identity problem.

But my parents immigrated here in the 1890s. They were in their teens. My mother was 14 and my father was 16 or 17. They were able to immigrate here. Why? Not merely because we had free immigration, but also, for example, because we had no minimum wage laws. Had there been minimum wage laws, there would have been no jobs for them to take. Minimum wage laws, like so many of these other interferences, though enacted in the name of helping the poor, in fact, deny the very poorest opportunity.

The basic point is sound, but Friedman once again overstates. His parents could have still worked illegally, or taken especially unpleasant jobs, or opened their own businesses. And if I were a Russian Jew in the 1890s, I would have tried any of these options to escape the czars even if the U.S. did have a sky-high minimum wage.

And you can go down the line. There would be no entrepreneurs willing to provide employment under the only kinds of conditions and with the only kind of jobs that they were qualified for. Now, of course, it's a very hypothetical thing because if they couldn't have emigrated to the US, they might not have met over in Carpatho, Ruthenia where they came from. And if they had met in Carpatho, Ruthenia, they might not have gotten married and if they had gotten married they might not have conceived me, and I had been conceived, and you can go on with all the rest of the ifs. But had I survived that particular area which was at that time part of Austro-Hungary, later of Czechoslovakia, is now part of the Soviet Union.

So he gets the non-identity problem after all. That’s my Friedman!

And you will see that I have come back full circle to my paradox about immigration. Because that's exactly why in the modern kind of a welfare state, free immigration is not really feasible, because in that kind of a state, we have gone too far in eliminating the function of the price system for distributing the income as well as providing information and incentives.

“Too far” is the kind of language he should have been using throughout. But if that’s what he’s really saying, why is Friedman so confident that free immigration to the U.S. of 1978 would be horrible?

And how would you reconcile your advocacy of open immigration with your support of a negative income tax, program which would have in effect a minimum income for every American?

It's a very good question because, of course, in that form, they are incompatible. I agree. And that leads back to the question of the negative income tax. If you are starting from scratch, if you did not have any welfare programs at all, if you were back in the situation when you did have open immigration, I am very dubious that I would be in favor of a negative income tax. I am not in favor of a negative income tax as a good thing in and of itself. I am in favor of it as superior to the present welfare mess, and as a way in which we can possibly move from where we are now to a situation under which you could have open immigration.

That’s my Friedman. Notice, however, that if Friedman is right about the superior work incentives of the negative income tax, his favorite welfare-state reform still makes immigration look better relative to the status quo.

I agree, today you could not have open immigration. You could not have open immigration because you do have essentially a guaranteed minimum income, whatever you call it. You have a guaranteed minimum income in the form of a large number of very varied and different kinds of programs, whether you include food stamps, Aid to Dependent Children, Social Security, SSI, and so on. They are a mess. They mean that people who are in the same position may get very different benefits depending on how many programs they can qualify for. It means that many people have a strong incentive not to work, and that by working, they only make themselves worse off and so on down the line.

Even if a welfare recipient’s effective marginal tax rate exceeds 100%, they are probably better-off in the long-run if they get a job. Why? Because getting a job is crucial for eventually getting a better job. Behavioral economics provides the intellectually strongest case against the welfare state. Namely: That government support encourages recipients to impulsively act against their long-run interests.

The immigration connection: The native poor are self-selected for impulsivity, and are usually part of a dysfunctional culture of poverty. So the negative effects of the welfare state on immigrants’ work effort is likely to be muted. Consistent with this story, poor immigrants have much higher upward mobility than poor natives.

At the same time, you cannot abolish all those programs overnight. You have some millions of people whom you have led to become dependent on those programs. If you hadn't had the programs, they wouldn't have been dependent, but there they are now. You cannot simply turn your back and say we're going to pull out the rug from under you.

That’s one side of the argument. The other side, though, is that shock therapy is the best way to break the cycle of poverty once and for all. If you believe in “cold turkey” for alcohol and drug addiction, why not welfare dependency?

You have to have some kind of a transitional device, and I have always viewed the negative income tax as a way in which you could have a program that would be far superior to the present structure, in that it would help people who are poor because they're poor. It would help them in a way which would retain an incentive for them to work, and at the same time, over time, you could gradually get out of the business by holding the amounts relatively steady, while the economy grew and grew.

Like other proponents of the Universal Basic Income (which is what Friedman’s negative income tax amounts to), Friedman glosses over major advantages of the status quo. But unlike normal UBI advocates, at least he has a viable long-run austerity plan.

And then, if you started in that direction, maybe you could eventually come to a position where it would be possible to have free immigration. Thank you.

In the spirit of my exchange with Friedman in Open Borders, he could just as easily claim that “if you started in that direction, maybe you could eventually come to a position where it would be possible to have free reproduction.” And that’s absurdly wrong. You could dolefully insist that the welfare state makes free reproduction ill-advised, but it’s plainly possible.

Dr. Friedman, in relation to your statements as far as Mexican immigration go, I'd like to make the following comment. And that is that, it seems to me that Mexican immigrants have a choice between, on one hand, staying in Mexico and getting what life they can, which to me seems like trying to evade starvation as long as possible, or crossing the river and then taking the job that they have available. And what I'm wondering is, is this choice a choice at all? And is it not equivalent to this gun against the head that you were talking about as absent from the free…

Who's holding the gun?

The capitalists in Southern California who own the…

On the contrary, in your image, it would be the Mexicans who are holding the gun. Well, they deny them the opportunity in Mexico.

Friedman and his questioner are both wrong. It is obviously the U.S. government that “holds the gun.”

There aren't enough capitalists in Mexico, as opposed to… Not enough jobs available.

Obviously, they have two bad choices. That doesn't mean that one isn't better than the other.

Well, yeah, I agree.

Friedman could fairly blame the Mexican government for hobbling Mexico’s economy with statist policies, but it’s still the U.S. government that prevents Mexicans from getting better jobs here.

And you must distinguish sharply between somebody giving you a choice, which is not a very satisfactory one, and somebody imposing something on you. Nobody is holding a gun to the head of these people and saying they should come to California. They are coming there because they believe they can have a better life for themselves and their children.

Indeed. What’s actually happening is that the U.S. government is holding a gun to their heads and saying they can’t come.

They can have a better one. Yes. But is it a life, or as you said yourself, no American would would like to do these jobs.

No, it's not that no American would like to. Many Americans would be perfectly willing to if that were their only alternative, but the Americans have better opportunities. Fine. How did the Americans get to have those opportunities?

By being American citizens? Is that the point you said?

No. No. By initially going through stages similar to that which the Mexicans are going through. They didn't, you know, people don't come full-blown into the world. The nations don't come full-blown into the world with skills and capital and so on. That all has to be derived through a long historical process.

They’re both right. Holding your actual skills constant, being born an American citizen has a huge effect on your lifetime earnings. The fact that countries only get rich through a long historical process is one of the best arguments for open borders, which allows people to leapfrog straight from Third World poverty to First World affluence.

I agree.

Then what's the alternative? If you say, well, we're willing to have the Mexicans in only if they can be supported at the level at which the Americans are supported, then you're condemning them to stay in Mexico.

“Condemning them to stay in Mexico.” Great language. When Friedman talks to pro-immigration libertarians, he’s anti-immigration. But when he talks to anti-immigration statists, he’s still pro-immigration.

But isn't it true…

So don't hurt them in order to help them.

<exasperation>For example, by opposing guest worker visas because you “don't think it's desirable to have two classes of citizens in a society”?!</exasperation>

Isn't it true that the wine growers in Southern California would prefer to have these Mexicans working at the rate they are working at than they are to have Americans come in and demand higher wages because of the alternatives they have?

They would prefer to pay lower wages rather than higher wages. You'd like to pay lower prices for the things you buy rather than higher prices. Of course, that's the whole system. That's exactly the system and if you say to the Mexicans, you may not offer to work for lower wages, then you're denying them the only weapon they have.

Note that the immigration restrictions that Friedman insists are absolutely necessary don’t just deny low-skilled Mexicans “the only weapon they have.” They deny their right to even enter the match.

But aren't you also…

That's why equal pay for equal work laws are a source of apartheid. You know, the basic source of apartheid in South Africa was the insistence by trade unions on equal pay for equal work. The women who go around today urging equal pay for equal work are being anti-feminist. They don't intend to be, but that is the effect of their policy. Because if there is any activity, in which for any reason, a male is preferable to a female, or vice versa, the only weapon the less productive sex has is to offer to work for less. And if you deny them that opportunity, you're assuring yourself that you're gonna have all-male jobs, or all-female jobs, or all-white jobs, or all-black jobs.

Overstated, once again. Even with a minimum wage, immigrants can compete by working illegally, doing especially unpleasant jobs, or self-employment.

But aren't you also condemning them to stay that way?

Not at all. Not at all. The typical course, if you go back to American history, by taking these low paid jobs, a great many people, not all, but a great many people were able to develop skills and activities, accumulate a little skill, a little capital, a little knowledge, improve their lot, become advance in the stage, get to a higher level of productivity, and get a higher income. That's been the typical way up the ladder for most of the people who came in here. It was a way up the ladder for my parents, for your parents, or grandparents, or great-grandparents. I don't know which. And that's the way in which, unfortunately, there's no way in which you can immediately propel people to the top of the ladder. Okay. Thank you very much. Thank you.

Fine.

You spoke a few times. You mentioned distribution of wealth.

Sure.

But most of what I've heard you talking about has been about distribution of income, rather than about the distribution of wealth.

Yes.

Now, you wouldn't argue, at least I hope you wouldn't, that the person in, let's say…

Okay. Sure.

Let's say, India is genetically inferior, say, to the person in America, is rather through the purely arbitrary circumstance of birth that he is in a country with a less-developed economy and or in a family that doesn't have as large a share of the capital. And that's not something that he is to blame for.

Oh, I'm not blaming anybody.

Even if the free market system equitably works and everyone progresses an equal amount, that person who started out with less a lesser share of the capital is still going to end up with a lesser share of the capital.

That's right.

Notice how hastily Friedman concedes (a) that genetics don’t matter for economic success, and (b) that poor Indians’ chief problem is lack of financial capital rather than draconian regulation of their human capital.

And there's nothing in the free market system that's going to enable him to make up for what was a purely arbitrary deficit in the first place. And given that the kind of people who become successful capitalists do not become that way by giving away their wealth voluntarily, isn't it necessary to forcibly redistribute wealth before you can begin to operate under a capitalist system?

No, it is not. Now, but let's examine this argument because, of course, it's true. There's no justice in the distribution of income or wealth. I never would argue there is. Those who are wealthy don't deserve to be wealthy any more than those who are poor deserve to be poor. It's pure accident.

A bizarre claim. Though the world is full of chance, the long-run tendency in almost any economic system is that smart, hard-working people with high self-control prosper relative to the general population. In a free market, this tendency is especially pronounced — especially if you remember that free migration is a crucial element of a free market. What could be more of an accident that being born in a poor country?

Perhaps Friedman relies on some Rawlsian premise that people don’t deserve their talent and character, but that hardly means that wealth and poverty are “pure accidents” in any meaningful sense.

And we might, but if you start to look at things that way, you're gonna go down the wrong line because you're gonna get back into this kind of a situation of destroying the good things, destroying what is possible in the search of an impossible ideal. The only way in which you can redistribute effectively the wealth is by destroying the incentives to have wealth. And the question is, what is the way, what is a system which will offer those people who are so unlucky as to be born without good positions, what is the system which will offer them the greatest opportunity?

A great question that leads us straight back to open borders.

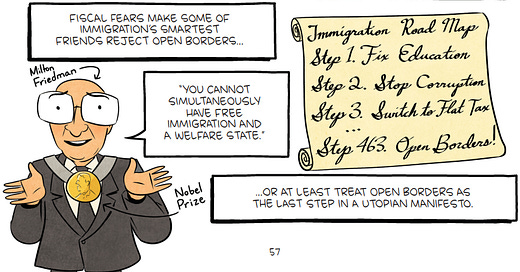

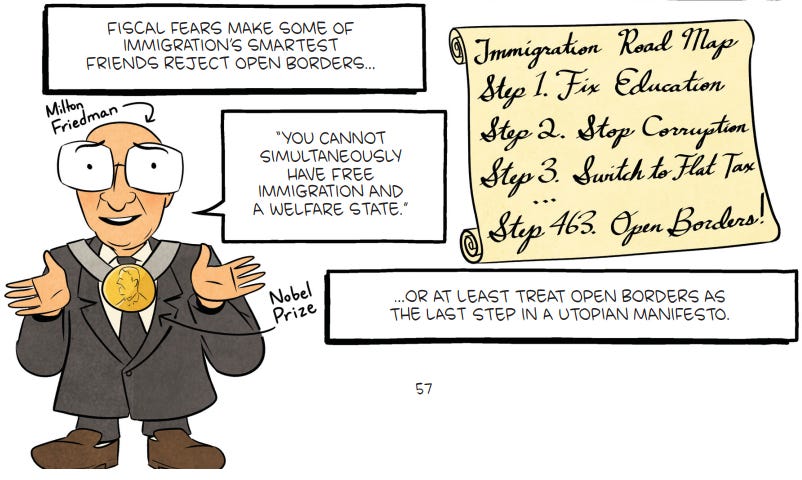

Summing up, Friedman’s take on immigration was genuinely better in 1978 than 1999. In 1978, he’s operating at a higher intellectual level, as evidenced by the extra qualifiers and caveats, not to mention his tangential nod to the non-identity problem.

Yet even at his intellectual peak, there is little sign that Friedman ever thought deeply about the economics of immigration. Yes, the welfare state makes free immigration less beneficial for natives and the world. But the benefits of free immigration are so immense that they remain highly positive after you slash them.

One of Friedman’s great strengths is that he routinely concedes the free market’s flaws, then argues that free markets are still the best option that humanity has. If he used this standard strategy to analyze immigration, he probably would have ended up with a position close to mine.

Instead, he lazily leaps from the mere existence of the welfare state to the “impossibility” of open borders. With all due respect, I would never quote Friedman on immigration even if I were a staunch restrictionist. Friedman was a brilliant social scientist; indeed, one of the all-time greats. But when he pontificated on immigration, he was usually asleep at the wheel.