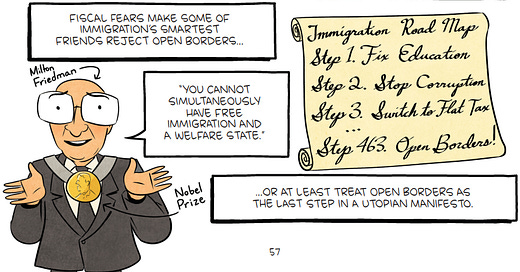

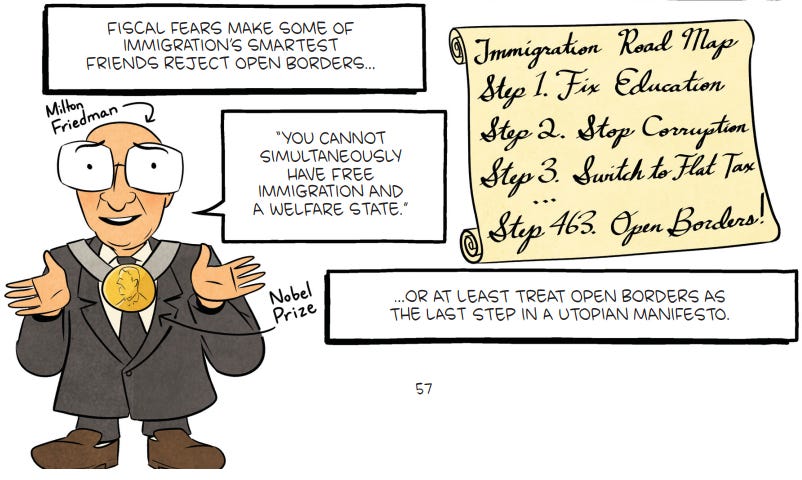

Friedman Contra Open Borders (1999)

What he said to the International Society for Individual Liberty

In 1999, Milton Friedman famously declared, “You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and free immigration.” I previously stated that Friedman made this statement during an interview with the International Society for Individual Liberty, but that’s not quite right. The quote actually comes from a post-lecture Q&A session. Thanks to Connor Tabarrok, I’m sharing the full transcript, with immigration-related segments in bold. Very lightly edited.

I’ve already criticized Friedman’s position at length in Open Borders and here, but I’ll post a point-by-point critique tomorrow. For now, here’s the immortal Friedman!

P.S. All the material about immigration is near the end, so if you’re short on patience, skip ahead.

To listen to people talk, everybody, everybody, with very few exceptions, and that's true particularly since the fall of the Berlin Wall, knows that socialism is a failure. Private enterprise capitalism has been a success. On the other hand, if you look at what actually goes on, the situation is very different. In country after country, governments are large and getting larger. Indeed, I've sometimes presented this as a kind of a syllogism.

Major proposition: Socialism is a failure. Minor proposition: Capitalism is a success. Conclusion: Therefore, we need more government. A conclusion that hardly follows from those premises, and yet that seems to be what's going on. But is it?

And that's what I really wanna talk about today, about the deeper view of the relationship between opinion on the one hand and practice on the other. It's very hard for people today to recognize how much change there has been in the climate of opinion in Western countries. When we were first getting started on the attempt to promote free markets, it dated back, for example, to Hayek's Road to Serfdom published in 1944. That was much reviled. Indeed it was hard to find a publisher to publish the book.

I think it was turned down by about a half a dozen publishers in the United States before it was finally published by the University of Chicago. And then, only because of the intercession of people in the economics department with the press. It, however, became a bestseller, was widely popular. In 1947, Hayek started the Mont Pelerin Society. Those were the beginning of the attempt to change the climate of opinion.

But how the people who were speaking that way, people like Hayek, like myself, were a very small beleaguered minority. The great bulk of opinion was that communism was a wave of the future. Collectivism, not necessarily communism, but collectivism was a wave of the future. How widespread that view, how isolated our view, the libertarian view was, is demonstrated by what happened to the books I myself have published. In 1962, I published Capitalism and Freedom.

It was not reviewed by any single major publication in the United States. Not by the New York Times, not by the Herald Tribune. It was reviewed in The Economist in London, and that's all. 20 years later, when we published Free to Choose, it was reviewed in every major newspaper. Over that period, there was a drastic change in opinion.

And that change in opinion has been reinforced by the fall of the Berlin Wall and is now almost universal. On the other hand, if you look what's ahead, at what's been going on in practice, it went the other way. To speak of my own country, in the United States, in 1947, government was spending something like 25% of the national income. Today, it is spending something over 35% of the national income. Moreover, there are many more regulations, restrictions on the behavior of both business on the one hand and personal individuals on the other.

There is no doubt that governments have gotten larger and much more intrusive. If you look at a wide range of other countries, I checked up on 20 industrial countries. In 18 of them, government spending in 1995, as a fraction of national income, was higher than it had been in 1975. How do we explain this divergence between the movement of opinion on the one hand and the movement of practice on the other?

The best explanation traces back to a book that was written at the end of the last century by A.V. Dicey, Law and Public Opinion of the 19th Century, in which he pointed out that there was a very long lag between changes in opinion on the one hand, and changes in practice on the other. More than a decade ago, my wife and I explored this phenomenon in an article entitled, “The Tide in the Affairs of Man.” We obviously took the title from Shakespeare. Here are Shakespeare's lines.

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

–Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

Our article discussed the hypothesis, and I quote, that a major change in social and economic policy is preceded by a shift in the climate of intellectual opinion. Itself generated at least in part by contemporaneous social, political, and economic circumstances. After a lag, sometimes of decades, an intellectual tide taken at its flood will spread to the public at large.

And through the public, pressure on government will affect the course of economic, social, and political policy. As a tide and events reaches its flood, the intellectual tide starts to end. We illustrated this hypothesis with the two most recent completed tides. The tides that we labeled, the Adam Smith tide, and the Fabian tide. Consider each of those.

Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations in 1776. At the time, he wrote in his book that it was idle to believe that the principles he espoused, the principles of free trade, would ever be accepted by the powers that be. It took a long time. The repeal of the corn laws, that is of the laws imposing a tariff on the import of grain, did not come until 1846, 70 years later. And then when that came, it swept away most of the restrictions, and laissez-faire reigned in Britain through the much of the 19th century.

The interesting thing is that although laissez-faire seemed to be bringing everything that its proponents had promised, the standard of living of the ordinary people in Britain rose greatly, there was an industrial revolution, Britain became the leading industrial nation of the world, and yet at the same time, the support for laissez-faire started to ebb. And you had the beginning of the next tide, the movement toward socialism, which we call the Fabian tide.

How do you explain that? Well there are a number of things that help to explain it. In the first place, as things got better, the evils that remained were more striking and prominent. You know, there are always problems in a society. You're never gonna have perfection.

That's for utopias for the next world, not for this one. And so having solved many of the problems which existed before, the remaining ones stand out. In the second place, one of the main forces helping the conquest of laissez-faire ideas was widespread corruption. In the 18th century, Britain was known as a land of smugglers. There was widespread evasion of the law.

There was widespread corruption of public officials. But under laissez-faire, when government had nothing to give, when there were no privileges it could grant, Britain developed an incorruptible, largely incorruptible, a very honest and efficient civil service. And therefore it became more feasible to think that government could do things, could do good. As you all know, the power to do good is also the power to do evil. In any event, in 1888, you had the establishment of the Fabian Society by the Webbs, by Shaw, by a small group of British intellectuals.

That was 1888. Its ideas, the Fabian ideas, gradually spread among the intellectual classes. And by within 20, 25, 30 years they were the standard climate of opinion on the intellectual level. But effects on policy did not follow for many years. The move toward a welfare state really only began just before World War I, with the beginning of the Social Security program.

And it didn't come to a full flood until after World War II, 1945, about about 60 years after the initial change in the direction of the tide of opinion. In the United States, much the same thing was true. In the, 1988, Edward Bellamy published his utopian socialist fantasy, Looking Backward. It sold a 1,000,000 copies, which is a tremendous sale in a country whose population was a great deal smaller than the population of the United States is now, if I remember rightly, under 100,000,000. And the ideas of socialism, the Fabian ideas, the Marxian ideas, all started to have their impact on the intellectual classes within the United States.

The first decades of the of the 20th century was the era, just before the World War I, was the era of muckrakers, of Ida Tarbell, of Sinclair Lewis. But action was very limited. The one action in the 1890s was trust-busting, but that had a different source. By the 1920s, after World War I, socialism was a dominant view among the intellectual class in general. Norman Thomas was a presidential candidate of the Socialist Party in 1928.

And his platform was widely accepted. However, policy did not change. Actual practice remained much the same, until the Great Depression. The Great Depression, which started in 1929, and really lasted throughout the 30s, had two effects.

On the one hand, it converted the general public at large to the view of the intellectuals. Whereas the public at large had regarded government as a necessary evil in the relatively laissez-faire 19th and early 20th century, it took the Depression, it regarded the Depression, as proving that there was something wrong with free markets and converted the public at large to the view that government, far from being a necessary evil, was the answer to all real problems. The result was the New Deal and the great growth of government supported by public opinion. Within a few decades, every single economic plank of the socialist 1928 platform had been enacted. So if you take the socialist platform of 1928 and read it today, it sounds like a very moderate platform that could be supported by either the Republicans or the Democrats. But it took a long time again.

That was opinion was changing in the United States in the 1890s, 80s. It was not until the 1930s or 40s, 50 years or so, before it really started to take effect. And then of course, the war produced another stimulus. But this in turn, just as the triumph of laissez-faire had led to the Fabian tide, the triumph of socialist ideas, and particularly their spread in the most extreme form, to Russia first and Germany later, led to what we've called the Hayek tide. Beginning with Hayek's Road to Serfdom, there started a gradual intellectual movement which gained adherence through time.

And it now led to the point where the overwhelming sentiment, in the nation at large is in favor of free markets. And yet as we see, the government continues to grow. But it's not an unmixed situation. Just as it took the Great Depression to change public opinion as opposed to intellectual opinion, the inflation of the seventies served very much the same function in the United States and around the world. And that was very much reinforced later by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The inflation of the seventies produced great doubts about the effectiveness of government in pursuing its very good objectives. The objectives of government, as you all know, are always very good. The argument is with the means and with the consequences of those means, particularly the unintended consequences of those means. You'll have to pardon me, but my throat gets very dry as I talk. And the result, the inflation of the seventies was a major factor that led the public at large to get disaffected and led to the election Thatcher in Britain and Reagan in the United States.

And they started a process of gradual dismantling of the all-powerful welfare state. You had, in the United States, a reduction in tax rates. In Britain, the same thing. You had a lifting of of price and wage controls in Britain. You had a lifting of foreign exchange controls.

You had a privatization and privatization continues to spread. You had some reduction in regulations. In all cases in the 1980s, both in Britain and the United States, you can say that you were really having an impact of the tide of opinion on actual practice. But unfortunately that was not very strong, and in my opinion, what has happened since the fall of the Berlin Wall has had a rather surprising effect. The fall of the Berlin Wall cemented the change in the climate of opinion.

It really made it universal. But it also led to undue complacency on the part of the West. After all, they were doing it all wrong and look at what happened to them. We're doing it all right and look at what's happening to us. We don't really have to change.

We can just keep on going it as it is. As a result, the pace of movement toward greater liberalization in the sense in which you and I would use the term liberalization slowed down while government did not grow as fast as it had before. It continued to grow in most of the countries or at most to stabilize in the United States. It's stabilized. Government spending today as a fraction of income is less than it was in 1983 when the Reagan revolution started to have its impact.

In Britain, it's about the same. But in many of the countries of Western Europe, spending today as a fraction of income is higher than it was then. If you look at the picture worldwide, you have to add another dimension which I've left out of it altogether. As our hypothesis stressed, these tides of opinion tend to be worldwide. They are not in a single nation.

Just as the the Adam Smith tide, the tide of belief in laissez-faire spread throughout the world, in its case very much promoted by the importance of the British Empire. Similarly the Fabian tide, the Marxian tide, the tide towards collectivism, towards socialism was worldwide leading in its extreme to what happened in Russia and later in Germany. So also the current tide is worldwide. And here again, it's interesting to note that the most dramatic impact of it has been in the communist countries. In China, ever since Deng freed up agriculture in the 1970s, you have had a very strong movement toward greater and greater free markets, greater and greater private enterprise.

The political structure is totalitarian. It has not changed. It is unacceptable. But there is no doubt that a conflict such as Tiananmen Square will emerge again because what is happening on the economic front is fundamentally incompatible with the political structure. If you take the former Soviet Union in countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, wherever you, Latvia, Lithuania, wherever you look in that part of the world, the tide of practice and not only of opinion has changed, they are far more, far closer to free markets than they were. They still have a way to go, of course.

On the other hand, Russia itself is in chaos, but Russia will not remain in chaos. I have no doubt that we will see many changes in the future, which will move in our direction. So if we look at the world as a whole, we can say that the contrast between the state of opinion on the one hand and practice on the other is part of a long-term cyclical process. And that is very important for our view because note that in each of these cases, as the tide of opinion started and did have its effect on actual practice, opinion itself started to end. It was just remembered when laissez-faire was at its height in Britain, that you started to have a change in the tide of opinion toward socialism and collectivism.

It was just as the effect of socialist opinion on practice was having its major impact when welfare states were worldwide, that you started to have a change in opinion away from socialism. And so those of us who believe in freedom and free markets have to watch and try to avoid getting caught in the same situation. It is when our ideas become more and more embedded in practice, there will be a tendency for opinion to shift the other way. So I conclude by saying that there is great reason for hope for those of us who believe in freedom and individualism. The tide of opinion has been reaching near its height.

It is having an impact on practice, but as so far only a small impact, but the lag is not so different as in these other cases. 1944, I start data the beginning of the Hayek tide. It's now 50 some years later and just about the same lag as you saw in the other cases. Thank you.

[Q&A starts here. Everyone but Friedman is in italics.]

Okay. Thank you very much, Dr. Friedman.

Thank you very much for such a wonderful speech, Dr. Friedman, and thanks for being with us. I have about a 1,000,000 questions here from the audience for you. I'll try to sum them up. The first one is, can the libertarian movement already be considered a tide and what will be needed for it to happen to become a tide if not?

I believe it is a tide. As I say, you go around the world and ask anybody, are you in favor of free markets? Do you believe that capitalism is a success? Is socialism a failure? You'll get the same answer almost everywhere.

Of course, you won't get that answer from the people in Beijing. You won't get that answer from many of the people in Washington. But if you ask people in general or in the business community, in the intellectual community, you know, there are very few Marxists left in the world. They're all in American universities.

Here's another question, Dr. Friedman. In Latin America, we're considering currency boards for full dollarization as the way to stop government, from printing money and generate inflation. He said Manuel Noriega from Panama could not print dollars and that was that was a great thing. In my country, Venezuela, the president has already printed money to finance their mistakes and corruption, and that goes on. And so your opinion about polarization for Latin America in general, and the second part of that question is whether a privatized monetary system based on a dynamic basket of commodities would be the way to go.

Unfortunately, I wish it were. But unfortunately, I think the experience of history is that you're not likely to get a privatized system. The only privatized system you had was when there was a widespread acceptance of gold, or silver as a monetary system. And even that was under government supervision. So I go back to the earlier things.

I think it is very important for Latin American and other countries, to end the situation in which the government can simply print money to pay for its debts. That does lead to inflation and disaster. And there are really only two solutions. One is to have a currency board. That requires eliminating the central bank.

Let me go back more generally. There are only three possible kinds of international financial connections. A country can have a flexible exchange rate. The peso can be free to find its own value in the market against the dollar. It can have and does have many countries do have a pegged exchange rate.

The government has a central bank which tries to peg to fix the value of its currency against the other country currencies. Peg it to the US dollar, peg it to the mark, peg it to the yen. And third, you're gonna have a truly fixed exchange rate through a currency board arrangement or dollarization. The one thing we have found out, and that we know for sure, is that the intermediate pegged exchange rates are a sure recipe for success [sarcasm]. A country will do better to have either a fully flexible exchange rate or a currency board or dollarization.

The real issue that arises is between, currency board and dollarization. And there is very much of a tendency for people to talk as if dollarization were the final solution for some countries. And maybe Panama has done very well by being dollarized. On the other hand, Hong Kong has done very well by having a currency board vis a vis the US. Argentina has done pretty well by having a currency board vis a vis the US.

And one thing you should keep in mind when you think dollarization means that you accept the Federal Reserve Board as your central bank. That's what it's equivalent of. Dollarization means that Venezuela, for example, would become a 13th, essentially the equivalence of a 13th district in the Federal Reserve System. At the moment, that looks like a very good arrangement. Because for the last 8 or 10 years, the US has had a very good monetary policy.

Price inflation has come down. Prices have been stable. The economy has been stable. But if you look back at the whole record of monetary policy under the Federal Reserve, it's been a very poor record. It's mostly been destabilizing, not stabilizing.

And you and Latin America have some experiences of this. Chile, for example, in the 1980s, got into serious trouble because it pegged its currency to the US dollar. The trouble wouldn't have been as bad if it had been dollarized, but it wouldn't have been very good. So do not take it for granted that US monetary policy will necessarily be good. I'm afraid that's too long an answer, but that's a subject I have a special interest in.

Thank you very much. Well, you know, just a follow-up to that question is whether if you have read The Creature from Jekyll Island, and what's your opinion on Griffin's recommendation?

If I have read what?

The book, The Creature from Jekyll Island, the book by Edward Griffin, and what's your opinion on his representation?

I haven't read it. Okay. No. I haven't read it.

Okay. Here's another question.

Noam Chomsky says that the free market libertarian ideology is just used by big corporate business to justify the practice of state corporate capitalism in practice. Can you comment on that?

Yes. I think there are problems, of course, of state corporate capitalism. I don't think, I don't think there's anything sacred about business.

What we are interested in is a competitive economy, not a government business economy. And there certainly are questions of state corporate capitalism. ADM, for example, which has been able to get the government in the United States to subsidize the production of methanol from corn. It's a disgrace and a scandal. So don't misunderstand me.

When I defend free markets and free enterprise, I'm not defending the governments as they now are. And the United States, you must recognize, is 50% socialist. If I take total government spending in the United States, it's about 35 or 4% of national income, but you have to include in addition the mandates that governments impose is the spending, which is demanded by government, but not paid for directly by government, such as requiring certain kinds of the pollution requirements, such as the ADA, which require expenditures on structures to enable disabled people and the costs to the country of rules and regulations. If you add that in the United States, the governments in the United States control about half the spending in the United States. So we're 50% socialist.

And what we hope for is that the tide of opinion will lead to a reduction in the scale and intrusiveness of government. So, the objection against government supported corporate capitalism is entirely justified. What we want is free-market, private enterprise capitalism.

Here's another question. Do you think a a voucher system will lead to the tumbling down of the private schools, the government schools, I guess, demand? Or do you think we should wait for the complete separation of school and state?

I would like to see a complete separation of school and state. My ultimate objective in this area is certainly a system in which government doesn't enter at all.

Parents should be responsible for their children's education and government shouldn't be involved. But you know, I've always thought that it's not enough for those of us who are trying to affect the course of events to emphasize what the ideal utopian solution would be. We also have to deal with the problem of how we get from where we are to where we want to be. There is not a chance in the world, in any country that I know of, of a practical, effective movement completely to eliminate government from the schooling. In every country, almost every country in the world, government plays a very, very large part. How do we move away from that?

And in my opinion, a voucher program under which government continues to spend money on schools, the money is attached to the child and not to the school. That's essentially what a voucher program is, the most effective way to move away from the present system and to move forward in the direction of the ideal.

Another question is there are several questions on taxes. One of them is, what was your role in the early stages of the invention of the withholding tax? And the second part of the question is, whether you think the income tax should be replaced by a flat tax or sales tax?

I have for many years believed that you should have a flat tax rather than an income tax. But again, we're talking of ideals versus realities. On the subject of withholding, I had nothing to do with the invention of withholding. Withholding is a very old thing.

It was widely adopted and used in in Britain and Germany all throughout Europe before it was used in the United States. However, during World War II, I was working at the Treasury Department for two years. And during that period, I was involved in the development of the withholding system that we now have in the United States. At the time, all we were thinking about was trying to finance the war. And it would have been utterly impossible to raise the taxes that were imposed at that time without withholding.

It's obviously a very… I shouldn't say obviously. It's not something that's desirable. On the contrary, it's very undesirable. You could not possibly maintain the present level of government taxation without the taxes being hidden. And they are hidden in two very different ways.

They are hidden through withholding. But they are also hidden by being imposed on business, supposedly on business, when really, of course, business can't pay taxes. Only people can pay taxes. So that, I think withholding is a very bad arrangement, but I don't know any way you're going to get rid of it. And I have to confess that I had a part in designing the present system.

What role of the state, if any, do you advocate?

I believe that you do need a state, and you need a government to have certain basic functions. The most important of those functions is to make the rules of the game. You know, we all speak of the importance of private property.

But private property is not a self-evident notion. You have to have some way of deciding where your property ends and where mine begins. If I own a house and you fly up an airplane a 100 feet over the top of my house, are you violating my private property? If you fly 10,000 feet, 20,000 feet, 40,000 feet, or again, we have houses next door to one another. You turn your radio and television set on at a very high amplitude.

Are you invading my private property or not? So how do you make those rules? And the basic function of government is, I think, first as a rule-making body. Second, as providing a mechanism for adjudicating disputes about rules. And third, as providing a means of defending the country against foreign enemies and individuals against private individuals.

Those I think are the three fundamental functions of government. And I would hope that you could do without them, but I don't believe it. However, I am not sure as a practical matter that there's any real reason to argue. My son and I, as you all probably know, David, my son, has written a book on a non-government, a complete libertarian system with no government. He and I disagree on that, but that doesn't mean that we disagree on any practical measures under consideration.

We're so far from where he would like to be and where I would like to be that we can move a long way together before we have any problems.

Dr. Friedman, do you think the state's war on some of the drugs is the result of an addiction to control the economy and the individual? Or it's just a lack of knowledge?

It's hard to answer that one. I believe it's obviously, I believe it's a mistake. And you see the problem with all of these things is, it's in a way easier to start a government program of that kind than it is to end it. There is no particular reason why we should ever have started on this, the absurd so-called war on drugs. But once you get it started, you establish vested interest.

We're spending tens of billions of dollars in the United States on the so-called War on Drugs. Who are the major supporters of the War on Drugs? The drug dealers on the one hand and the government people who are fighting them on the other. Those are the people who have a strong private interest in maintaining it. And who are the people who have a strong private interest in eliminating it? Unfortunately, they are mostly the drug addicts who have very little political power. It's, but even there, I think opinion is shifting in the United States and there is more and more recognition that the so-called war on drugs is doing far more harm than it is good, even in terms of its own objectives.

There's another question. Do you think that the USA was a libertarian society in the first half of the 19th century? And if so, if your answer is yes, how do we get back to that point?

I think the the US, yeah, it's not only the first half of the 19th century. I would say that the US was about as close as you're going to get to a libertarian society, up until about the First World War. There was the episode of the Civil War which interrupted that. But even then, throughout that whole period, if you take the whole period of 19th century up indeed, up until 1928, except for periods of war, total government spending in the United States, federal, state, and local, never exceeded about 10% of the national income.

And so that's a pretty good measure of a fairly libertarian society. It was far from a complete libertarian society. You had tariffs throughout the period. You had other restrictions, but it was about as close as you're going to get. Now, that was partly a pure accident to begin with.

And really, it's funny that the question should be about the first half of the 19th century because in the first half of the 19th century was when you manifested collectivist tendencies. In the 1820s and 30s, you had state after state, which established a state bank, the Bank of Ohio, the Bank of Indiana. You had the government starting to build railroads. You had the government, engaging in in industrial activity. So you had a movement toward what you would today call socialist.

What happened was that in 1837, there was a financial panic and almost all the government enterprises went broke and collapsed. And that is what was a major factor that led to the triumph of some of quasi-laissez faire for the rest of the century. Now the question is how you get back. There's only one way to get back. And that's fundamentally the only way to get back is to cut down the amount of taxes government receives.

I don't see any other way of reducing the scope of government. It's receipts. And that's why I have always been in favor of any tax cut of any kind of any form, however you can get it, whenever you can get it.

Question, Dr. Friedman, when did you decide to identify yourself as a libertarian? Was there a special incident that triggered that decision?

No. There was not. I've always called myself a classical liberal or a libertarian sort of equally. I really can't. I can't pick out any particular point. I have had those views, for well over 50 years. I don't know.

Thank you very much. There's another question. Should the USA open its borders to all immigrants? What's your opinion on that?

Unfortunately, no.

And I say unfortunately. You cannot simultaneously have a welfare state and free immigration. I am in favor of free immigration, but not if you have a welfare state. The United States had free immigration at the end of 19th early, throughout 19th century, and up until World War I, really. But that was possible because the United States was not a welfare state.

When my parents came to the United States at the end of 19th century, they didn't get any welfare when they got here. They were able to exist by the charity of relatives who had come here earlier. They were able to make their way in a free market and therefore people only came here. People came to the United States in order to use their resources and their capacities and were productive and help themselves and help the rest of the people who are here. But if you have a welfare state in which immigrants as in now are eligible to receive relief, to receive, benefits, and so on, you have people immigrating, not in order to use their resources in a productive way, but as it were, to be parasites on the rest of the society.

And unfortunately, there are an unlimited number, an infinite number of supply of people who want to live on somebody else's expense. And so the result of that is that unfortunately, you cannot have completely free immigration, in my opinion, in a welfare state.

Thank you very much. Here is another question. What is your opinion on natural monopolies? Do you think it is better for them to be public or private?

I think it is better for them to be private. And I think it's better for them for to be private because there are very few natural monopolies that last indefinitely. Almost always there are alternatives. There are are other things will develop.

The market, especially if a natural monopoly tries to exploit its monopoly power, it establishes an enormous incentive for people to find ways to compete with it, to destroy its monopoly character. If it's in the hands of the public, if it's in there, I shouldn't say the public, you don't mean public, you mean in the hands of the government. After all, the private enterprise is a public enterprise too. But the question is, should the monopoly be governmental or private?

If it's governmental, then the government will see to it that competition is suppressed and will prevent the monopoly from being destroyed. If it's private, the government may also get involved and undoubtedly will regulate it. But that will probably increase the opportunities for other people to compete. So you're more likely to get rid of monopolies. But let me make a factual point.

It is very difficult to find any real natural monopolies. Almost all actual monopolies are monopolies because of special privileges and grants that they get from the government.

Okay. Thank you very much Dr. Friedman. Here's another question.

What is the most important thing to do in our countries, and I refer to Latin American countries where the government has de facto control of so many businesses through monopoly ownership, in order to defeat? What should be done in order to defeat their influence and power?

Well, I think the most effective way to do that is through pressing for free trade. International competition is a most effective way to destroy local monopoly power. Obviously, as you all know, in every one of your countries, you want to try directly to reduce the role of government as best you can.

But generally speaking, trade is a more effective solvent than most other mechanisms.

Here is another question. You said, when somebody in the audience said, you have said that the opinion can lead to either the reduction or expansion of the state. But what would you say to this? What would you say to this proposition? The state takes on a life of its own. It wants to grow and live. Therefore, it is much more likely that opinion can lead to the growth of the state than to shrinking it.

Well I think there's a great deal of merit to that position.

Indeed, if you take a broad view of history, if you look at a broad range of history over time and over space, most people, most of the time, have lived under tyrannical government. “The natural course of events,” as it were, is toward big government, not toward libertarianism. The real miracle is when you're able to get a libertarian as opposed to a state-run society. So I think there is a great deal of merit to that proposition.

We are very fortunate to be living in that rare piece of time. And some of us, not all of us, in countries which have been largely, relatively free countries. Freedom is not the natural state of affairs. Tyranny is a natural state of affairs.

Thank you Dr. Friedman. Here's another question. What do you think of the World Trade Organization and its role for free trade?

Yeah. I understand. I am not enough of an expert on that to be able to make an intelligent comment. I would like to have just, I have always been in favor of unilateral free trade whenever you can get it. The same thing goes with these, treaties like NAFTA, like the European community and so on.

They are halfway houses. It would be far better if each country separately went into free trade. But again, you have to recognize the problem of getting from here to there. And such regional agreements are most of the time a way to go. And similarly, the WTO is probably an effective device for promoting more trade. Although in an ideal world, it should not exist.

Here is another question. Which person had the greatest influence on your economic philosophy and why?

It's very hard to answer that question. I'm sure that my economic philosophy was very much influenced by some of my teachers in undergraduate and in graduate school.

Arthur Burns, Homer Jones, Frank Knight, Jacob Viner, and then later by Fritz Hayek.

Thank you. Here's another question. What is the most free country at the moment?

That depends on whether you mean economically free or politically free.

No doubt that even up to the present, Hong Kong remains the economically most free. But it's a very interesting case because although economic freedom does promote a tendency toward political freedom, toward human freedom, those are not all not the same thing. In fact, you have economic freedom, you have human or civil freedom, and you have political freedom. Hong Kong, until the transfer to China, was the best example in the world of the combination of economic freedom and civil freedom with 0 political freedom. Hong Kong was essentially a case of benevolent dictatorship with Britain the dictator.

And it was pure accident that as it happened, the person who was set out, to sort of run Hong Kong in the early late forties early fifties, promoted free markets in Hong Kong at the same time that Britain at home was promoting socialism. So I would say that in terms of the economy, probably Hong Kong, in economic terms is a free, but it's not a politically free country. And it's losing its civil freedom as China is playing more and more of a role. Now if we go beyond Hong Kong, I would say that, probably the US well, I obviously have a bias, but I think the US with all its defects and all its problems, is probably overall the freest country, both politically, civilly and in economic terms. But, that may show my own ignorance.

Certainly New Zealand is a country that deserves to be considered. It's moved very far in the direction of free markets. It has, in the last 15, 20 years. And Britain has many elements of effective free markets. So, what you have is, you have nowhere in the world a major country that has gone as far toward freedom as you and I would like. But you have some that are, you know, better than others.

Thank you very much, doctor Friedman. Can we ask you one or two more questions?

Yes, sure. Okay.

Here's one question. Do you oppose, do you oppose a unilateral reduction of tariffs? And if not, how can you oppose the open immigration until the welfare state is eliminated?

I am in favor of a unilateral reduction of tariffs. But the movement of goods is a substitute for the movement of people.

I, as long as you have a literal welfare state, I do not believe you can have a unilateral open immigration. I would like to see a world in which you could have open immigration. But stop kidding yourself. On the other hand, the welfare state does not prevent unilateral free trade. I believe that they are in different categories.

Thank you. Here's a follow-up, basically follow-up to that question says, that instead of a green card, can the USA issue a blue card, which the blue card does not give welfare?

That would be if you could do that, that would be fine. Okay.

But I don't believe you can do that. I believe it's not only that it's not politically feasible. I don't think it's desirable to have two classes of citizens in a society. We want a free society. We want a society in which every individual is treated as an end to themselves.

We don't want a society in which some people are in there under under blue conditions. Others are in there under red conditions. Others are in there under black conditions. We want a free society. So I don't believe such, I haven't really ever thought of that system.

It's a new, I very rarely get a new question, but I must admit that's a new question for me. And I haven't really thought about it a great deal, but my initial reaction is, that it's a very undesirable proposal.

Well, Dr. Friedman, we want to end the question here and this link with you. We're so thrilled that you could be with us and talk to us directly as if you were here. The audience is is ecstatic. So thank you very much. Thank you very very very much.

Well, thank you for having me. I'm delighted to have participated.

Goodbye.

Alright. Goodbye.

Okay.

The existence of welfare does not deter me from favoring open borders. I want open borders; I don't want welfare.

Let them both try to coexist (they can't) and may the better system win.

Its interesting to see how things have changed since 1999.

The supposed stabilization of government spending under Reagan didn't last and is much higher now. The likely force being that immigrants moved the median voter to the left.

We more or less did give up on the War on Drugs, and now everyone seems to not like the new legalization world.

School vouchers got passed in some places, but only through right coded culture war means.