Hopeless Excuses

Suppose I’m right about mental illness. Telling people they’re “sick” might still be a noble lie that makes them feel better. But the reverse is also true: Even if I’m wrong, telling people they’re “sick” might be harmful. Perhaps the mentally ill are better-off believing they can free will their way out of their troubles. As the noble Jason Brennan often reminds us, we should scrupulously separate specific empirical questions from our general philosophical outlook.

In “Effects of a Chemical Imbalance Causal Explanation on Individuals’ Perceptions of Their Depressive Symptoms,” (Behavioral Research and Therapy, 2014), Kemp, Lickel, and Deacon run a fascinating on-point experiment. How does belief in the “chemical imbalance” theory of depression actually affect depression? The set-up: Researchers started with a sample of students who had experienced depression, then:

Participants were randomly assigned to the chemical imbalance condition or the control condition. Following informed consent and collection of demographic information, participants were administered the “Rapid Depression Test” (RDT). The RDT was described as a test of neurotransmitter levels whose results would allow participants to determine whether or not their depressive episode(s) were caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. Participants were led to believe the purpose of the study was to improve understanding of how individuals respond to learning the cause of their depression, before release of the RDT into clinical practice. The test procedure entailed swabbing the inside of the participant’s cheek with a sterile cotton swab and placing the cotton swab into a sterile collection container. Next, the experimenter (a male undergraduate research assistant wearing a lab coat) instructed participants that he was leaving the experiment room to take their saliva sample to the lab and run the test. The experimenter returned 10 min later with the condition-specific results of the RDT. In the chemical imbalance condition, participants were informed that test results indicated their current or past depression to be caused by an imbalance in the neurotransmitter serotonin. Participants were presented with a bar graph of their test results (see Fig. 1) depicting very low serotonin levels relative to levels of other neurotransmitters, all of which were in the normal range. In the control condition, participants were told their past/current depression was not the result of a chemical imbalance, based on purported test results (and a corresponding bar graph) indicating that all neurotransmitter levels were in the normative range.

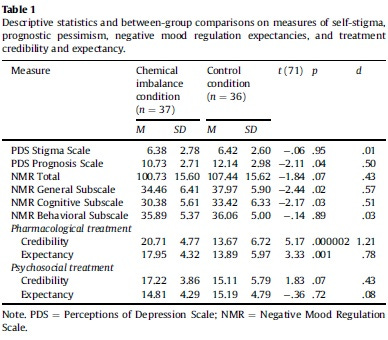

Qualitative version of the experimental results:

[C]hemical imbalance test feedback increased prognostic pessimism, lowered negative mood regulation expectancies, and led participants to view pharmacotherapy as more credible and effective than psychotherapy. These effects were not offset by reduced stigma, as chemical imbalance feedback had no effect on self-blame. Overall, the present findings suggest that providing individuals with a chemical imbalance causal explanation for their depressive symptoms does not reduce stigma and activates a host of negative beliefs with the potential to worsen the course of depression and attenuate response to treatment, particularly psychotherapy.

While none of these effects are huge, we shouldn’t expect a brief experimental treatment to deeply sway people’s psychiatric worldviews. It’s entirely plausible, though, that a whole-hearted conversion to the “chemical imbalances” view would do many times the damage (“iatrogenic effects“) of a marginal change in the same direction. Intuitively, moreover, the results make sense. Feeling helpless is a high price to pay for feeling blameless.

To repeat, none of this shows the chemical imbalances view is false. But it does show that accusing Szaszian skeptics of lack of empathy for human suffering is unfair. Telling troubled people, “Your bad brain chemistry is beyond your control, it’s not your fault” may sound compassionate, but they seem to hear a bleaker message.

The post appeared first on Econlib.