How to Make *Defending the Undefendable* Defensible

My essay for the Walter Block Festschrift

When the truth is ugly, people lie. Psychologists call this “Social Desirability Bias.” Human beings exaggerate their patriotism and piety, their altruism and loyalty, their intelligence and their tolerance. Social Desirability Bias (SDB) is embedded in language itself: When someone asks, “Would you like to come to my party?,” you refuse with “Sorry, I can’t” even though that is almost never literally true. Sometimes these lies become so ubiquitous that we lose awareness of our own dishonesty.

Until a brave soul like Walter Block loudly challenges our collective mendacity.

In 1976, Walter Block published his most controversial work, Defending the Undefendable. Subtitled The Pimp, Prostitute, Scab, Slumlord, Libeler, Moneylender, and Other Scapegoats in the Rogue’s Gallery of American Society, the book famously divided the libertarian world when it was first released. The Mises Bookstore charmingly provides a long inventory of positive and negative reviews. Hayek, Rothbard, Hazlitt, Nozick, and Szasz all praised it; Nathaniel Branden, Sharon Presley, Laissez-Faire Books, and Walter Grinder all panned it. The latter bluntly called Defending the Undefendable, “An absolutely mad way of introducing someone to libertarianism.” The most memorable assessment, however, was Roger MacBride’s: “It is a magnificent book, a trailblazer. I would call it ‘Drano for Clogged Minds,’ except that Drano is neither amusing nor stimulating, and this book is both.”

Block’s Defending the Undefendable is remarkable precisely because it turns SDB on its head. Instead of telling readers what they want to hear, Block tells readers — even staunchly libertarian readers — the opposite. He explicitly names counterfeiters, misers, heirs, slumlords, and even “male chauvinist pigs” as “heroes.” And he urges readers to rethink their condemnations of pimps, prostitutes, drug pushers, and addicts. The opening of his chapter on “The Drug Addict” remarks:

At the present time, with the intense discussion on the evils of heroin addiction, it is well to heed the old adage - “listen to both sides of the story.” Among the many reasons for this, and perhaps most importantly, is the fact that if everyone is against something (particularly heroin addiction), one can assume that there is something which can be said in its favor. Throughout mankind’s long and disputatious history, the majority opinion has, the majority of times, been wrong.(p.33)

As a vocal enemy of Social Desirability Bias, I am naturally sympathetic to Block’s project. And on inspection, many of Block’s notorious arguments in Defending the Undefendable turn out to be correct. Truly, you don’t help the poor by banning low-cost housing and low-skilled jobs. His defenses of moneylenders, “slumlords,” “ghetto merchants,” speculators, importers, middlemen, profiteers, employers, “scabs,” and “rate busters” are compelling applications of microeconomic logic. Block’s chapter on “The Gypsy Cab Driver” verges on visionary: “A proper solution to the taxicab crisis is not to co-opt the movement of gypsy cab drivers by the offer to take them into the system, but rather to destroy the system of restrictive cab licenses.” Decades later, Uber and other ride-sharing services defeated traditional tax licensing with Blockian heroism by openly breaking the law.

Unfortunately, other notorious arguments in Block’s classic work turn out to be incorrect, or at least overstated. The lesson of Social Desirability Bias is to disregard ugliness when we assess truth, not to embrace the antinomian view that ugliness is a sign of truth — or that the truth is whatever position is maximally ugly. Reading Defending the Undefendable, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Block occasionally gets carried away by contrarian joy.

Unlike most of Block’s critics, however, my goal is not to refute his work, but to fix it: to make Defending the Undefendable defensible. After identifying flaws, I propose mostly moderate revisions to get the project back on the track of truth.

Error #1: Ignoring human irrationality. Throughout his book, Block consistently ignores the possibility that human beings systematically misunderstand their own interests. He is right, of course, that…

After considering the good features (short hours, high remuneration), with the drawbacks (harassment by the police, enforced commissions to her pimp, uninspiring working conditions), the prostitute obviously prefers her work, otherwise she would not continue it. (p.4)

The same goes for drug addicts and misers. They, too, think that the good features of their lifestyle outweigh the drawbacks. Block concedes that these actors might be mistaken: “The prostitute may feel that the money she was paid did not fully compensate her for the services she provided.” (p.4) The key question is: Are the mistakes of the prostitute, addict, and miser systematic — foreseeable via common sense?

In his discussion of drug addiction, Block seems to reject this idea on principle: “Since there is no objective criterion for such choices, there is nothing irrational or even suspect about any choice on the spectrum.” (p.35) But this is awfully dogmatic. Suppose Block was advising a young person that he cared about. If the advisee said, “I’m considering prostitution,” “I’m considering drug addiction,” or “I’m considering becoming a miser,” would Block agnostically reply, “As long as the good features outweigh the drawbacks, go right ahead”? Unlikely. Instead, he would more helpfully respond, “That’s a bad idea, because the drawbacks almost always outweigh the good features.” Or at least he should.

Block often appeals to the ugly truth of continuity. He correctly observes that prostitutes are hardly the only people who factor money into their sexual choices: “Many dating patterns clearly conform to the prostitutional model. The male is expected to pay for the movies, dinners, flowers, etc., and the female is expected to reciprocate with sexual services.” (p.6) This hardly implies, however, that prostitutes are choosing just as rationally as anyone else. One can consistently advise against prostitution and advise in favor of considering a romantic partner’s career prospects. Why? Because some ranges of “the spectrum” are prudent and others aren’t. We don’t need perfect precision to acknowledge this truism.

How much of Block’s position can we salvage after conceding the reality of human irrationality? Quite a lot.

To start, Block could credibly argue that while prostitutes, drug addicts, and misers systematically overrate the net benefits of their choices, the rest of us systematically underrate the frequency of exceptions to this rule. Some prostitutes are very highly-paid relative to their next-best career options; some prostitutes have unusual personalities that allow them to enjoy — or at least not badly mind — their work. Not only are some addicts high-functioning; some plausibly function better with their drug of choice than without. Some misers, similarly, get little joy from material consumption, but have expensive long-run entrepreneurial or philanthropic goals that fill their lives with meaning.

Another line of argument consistent with Block’s outlook is the arbitrariness of the list of acceptable paternalisms. Many forms of severe irrationality pass almost unnoticed. Almost no one wants to do much about adults’ poor romantic choices — even when two mismatched twenty-somethings legally promise to stay together until “death do they part.” The same goes for religion. No more than one religion can be true, and people’s lives and potentially afterlives hang in the balance. Yet again, the default position is that even the least mature adults should be allowed to theologically make up their own mind and make their own mistakes. Why do we view prostitution and drug addiction any differently?

Finally, a thorough review of Table of Contents of Defending the Undefendable reveals several cases where, contrary to popular prejudice, irrationality is the exception rather than the rule. If a rich man lived and shopped in a “slum,” we might question his rationality, but for a poor person, these choices make sense. The same goes for child labor. Yes, we can easily imagine a minor making horrible job choices. Normally, however, as I explain in my The Case Against Education, a job is a fine way for youths to earn money and acquire valuable human capital at the same time.

Error #2: Ignoring (almost all) externalities. The initiation of physical force against person and property is a classic negative externality that Block is ever-ready to condemn (though not in those words). He is also happy to point out any negative side effects of the initiation of force, especially if the government is the initiator:

It cannot be stressed strongly enough that these crimes are due to the prohibition of heroin and not the result of heroin addiction. It is the prohibition that drastically forces its price up and drives the addict into a life of crime and brutishness which may end in his own death or that of the victim. (p.29)

But Block studiously ignores all other negative externalities produced by the “scapegoats” that he champions. Without regulation, yes, prostitutes, pimps, drug addicts, and drug pushers would mostly do their business out of the public eye. But they would still break up marriages and leave children in broken homes. Without public property, yes, we wouldn’t worry about littering. But public property covered in trash is still much less pleasant than public property not so covered. And libel and slander can spread at least as easily on private property as public property.

Block tries to deflect these criticisms with further appeals to continuity:

Another argument leveled against addiction is that it prevents people from fulfilling their responsibilities. The example usually given is that of a father who, under the continuous influence of heroin, becomes incapable of fulfilling his financial and other obligations to his family. Let us assume that heroin addiction incapacitates the father. It still does not follow that the use and sale of heroin should be prohibited. It would be unreasonable to prohibit any activity on the grounds that it prevents some people from functioning in certain ways. Why should the people who are not impaired or who do not have like responsibilities be restricted? Were it proper to prohibit heroin for this reason, surely it would also be proper to prohibit gambling, drinking, smoking, automobile driving, air travel, and other dangerous or potentially dangerous activities. But this would be patently absurd.

Should heroin be legal for some people but not for the others who do not accept or fulfill their responsibilities because of their addiction? No. When a man, to continue the example, marries, he does not agree to renounce all activities which might be dangerous. The marriage contract is not, after all, a slave contract. Marriage does not prevent either party from engaging in activities which might discomfort the other. People with responsibilities do get heart attacks from playing tennis. But no one would suggest that people with responsibilities be barred from sports activities. (p.35)

The common-sense response, again, is that size matters. Suppose Walter Block was offering marriage counseling to a young person he cared about. If the advisee confessed, “She’s furious that I spend $10 a week on chewing gum,” Block would probably respond, “Nobody’s perfect. If that’s her top complaint, she should count herself lucky.” In contrast, if the complaint said, “She’s furious that I spend 90% of our money on heroin,” Block would probably respond, “That’s a terrible way to treat your spouse. You need to stop at once and make amends.”

How much of Block’s position can we salvage after conceding the reality of externalities? Again, quite a lot.

To start, we must remind ourselves that the negative externalities of these disfavored activities are usually small or non-existent. To use my slogan, “Abusers give vice a bad name.” Severe drug addicts are highly visible in some urban areas, but most users consume in moderation. Prostitutes can break up marriages, but many of their customers are single, or in relationships with partners who do not strongly object. Most libel and slander gets ignored and persuades no one.

The argument from arbitrariness is relevant as well. Alcoholism plausibly destroys more families than drug addiction. Infidelity with non-prostitutes plausibly destroys more families than infidelity with prostitutes. But the law and public opinion largely overlook the former and harshly punish the latter.

Indeed, once we take externalities seriously, we can actually improve some of Block’s arguments. Yes, blackmailers create negative externalities for their targets. But they also create positive externalities for the rest of society by deterring blackmailable behavior! Legalizing blackmail would plainly discourage adultery, child abuse, embezzling, and much more. Furthermore, while spreading insulting falsehoods is a plausible negative externality, spreading insulting truths is a plausible positive externality. If Jones is a lazy worker, employers ought to know, right? Yet the threat of libel and slander lawsuits almost certainly discourages the spreading of all insults regardless of their truth.

Error #3: Exaggerating “heroism.” Murray Rothbard’s introduction to Defending the Undefendable warns that Blocks’ scapegoats are “Heroes yes, but not necessarily saints.” (p.xi) But even calling them all “heroes” abuses the English language. True, Block’s proposed criteria sound reasonable:

[T]hree criteria for heroic actions must be applied. The act must not violate the rights of innocent people; the act must be of great benefit to large numbers of people; and it must be performed at great personal risk. (p.109)

Indeed, Block’s appeal to "great benefit to large numbers of people” comes close to endorsing the notion of “positive externalities.” He just needs one caveat: He should have specified a “great net benefit” to rule out actions that help many people but harm even more.

That aside, Block neglects another crucial feature of heroism: motive. In ordinary language, an action isn’t heroic if its sole motive was amoral.

In any case, even if we accept Block’s criteria, his “heroes” often fail to qualify. Take the drug addict. Drug addiction per se does not violate the rights of innocents, and does entail considerable risks. How, though, is addiction “of great benefit to large numbers of people”? For littering, Block has a case if the litterer loudly announces that he is littering in order to protest the injustice of public property. But this virtually never happens. Actual littering fails on two of his three criteria. Normally, the litterer is virtually the sole beneficiary of his action — and the personal risk is slight.

How can we amend Block’s position?

The first step is to tone down the praise. Instead of calling his scapegoats “heroes,” just say that their actions are “potentially heroic.” While the typical prostitute is no hero, sex worker/Substacker Aella arguably qualifies because she really does publicly stand up for her rationalist moral principles.

The second step is to dwell less on the questionable virtue of the scapegoats and more on the glaring vice of the scapegoaters. At minimum, the scapegoaters are morally negligent. Drug warriors, for example, rarely even try to explain why their crusade is any better than alcohol prohibition. Most of the time, moreover, the scapegoaters are worse than morally negligent. Middlemen, “profiteers,” and many of the other occupations they attack actually turn out to be vital for human well-being.

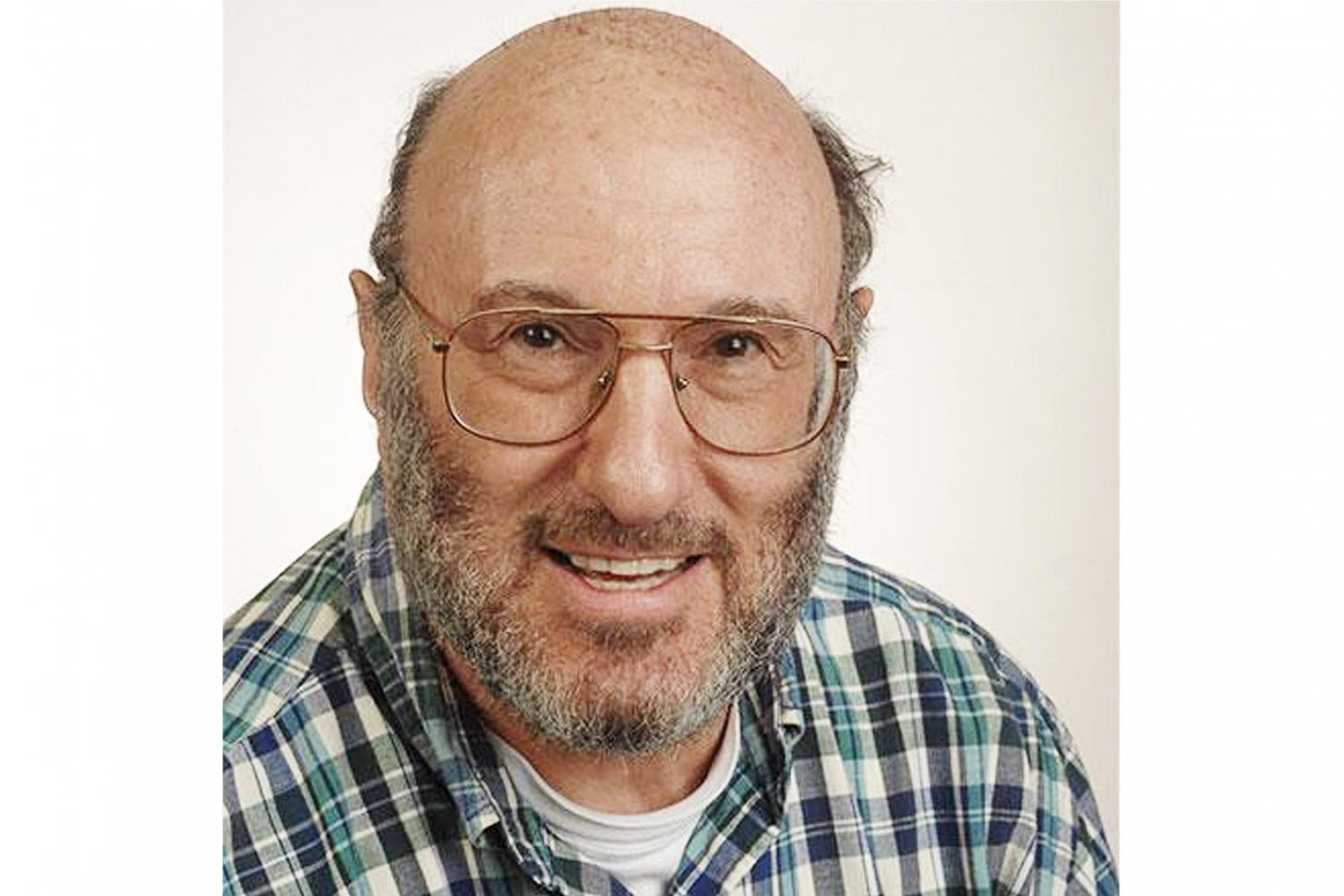

Walter Block is a tenacious debater, and his commitment to Misesian economics is legendary. I would be amazed if this short essay changed his mind about anything. My chief goal, however, is to persuade critical friends and friendly critics that Block’s infamous praxeological book deserves a psychological reformulation. Though he never mentions Social Desirability Bias by name, Defending the Undefendable is a brave defense of “ugly truths” over “pretty lies.” Why not focus on that, instead of continuing to insist that human behavior is always rational and that externalities are a myth?

Postscript

An economist in my department once described Walter Block as “the biggest jackass in all of economics,” but my earliest memory of Walter is indelibly positive. We met at the 1989 Ludwig von Mises summer seminar at Stanford University when I was straight out of high school. After introducing myself to “Professor Block” on the way to class, he affably responded, “Just call me Walter.” I enjoyed the whole week arguing with this first-name-basis professor. While in college, I actually sent him letters (not emails) — and Walter graciously mailed back in-depth replies. Once I became a professor, Walter replied to my critique of his cherished Misesian brand of economics. Then I replied, then he replied, then I replied, then he replied again. I let him have the last word, so according to Block’s “Whoever published the last word in a debate, won the debate” standard, he was victorious. A Festschrift often accompanies a scholar’s retirement, but I for one hope that Walter stays the course. Remember, old friend: Never retiring is the best revenge.

Even if they're not exactly right on everything (who is?) the Austrian economists and Mises Institute produce more content that's accessible to the general public than anyone else. I don't think it's even close. They do a tremendous job of trying to teach lay people economics and libertarian theory. Your story of back and forth correspondence with Block is great anecdotal evidence of this as well. If it weren't for them I wouldn't know half of what I do today about economics or libertarianism.

Their ardent defense of free markets that verges on dogmatism doesn't bother me either. I would take a million times more of it to balance out what people normally think and hear. I prefer your approach, to be sure, but I still find what they do incredibly valuable. To call him the biggest jackass is really myopic.

"Error #1: Ignoring human irrationality. Throughout his book, Block consistently ignores the possibility that human beings systematically misunderstand their own interests."

People can "systematically misunderstand their own interests" and make all sorts of mistakes. But is this really "irrationality"? Using their reason, people attempt to act as they think is best at that moment in the perceived circumstances. That people are always rational in this sense, is why we should reason with them rather than dismiss or override their choices as being "irrational". https://jclester.substack.com/p/adversus-adversus-homo-economicus