I recently argued that self-reports understate the personality gender gap. As long as some men rate their personalities relative to the average male, and some women rate their personalities relative to the average female, the gap the data reveal is less than the true gap. Indeed, if everyone gender-norms their responses, researchers will detect zero gender gaps in personality no matter how massive they are.

The same principle also implies that self-reports understate the magnitude of immigrant assimilation. How so? Well, suppose you migrate from a highly religious country to a secular country. The day before you arrive, you say you’re “highly religious.” Twenty years after you arrive, you still say you’re “highly religious.” Does this show you didn’t assimilate at all?

Hardly. The day before you arrived, you were probably describing yourself as “highly religious” by the standards of your country of origin. Twenty years after you arrive, you are probably describing yourself as “highly religious” by the standards of both your country of origin and your country of residence. Why? Because you keep comparing yourself to the kinds of people you’re familiar with. Before you came, almost everyone you knew came from your country of origin. Twenty years later, you know a mix: friends and family who never left, fellow immigrants, plus all the other residents of your new country. When asked “How religious are you?” it’s only natural for you to recalibrate your religiometer.

That’s for first-generation immigrants. For second-generation immigrants, the understatement of assimilation is probably much more severe. Suppose the child of Saudi immigrants describes himself as “highly religious,” just like his parents. A naive comparative sociologist will conclude that the child hasn’t assimilated to his secular culture at all. Yet it is quite plausible that the child actually assimilated almost 100%.

How? Simple: The immigrant parents have lived in two societies, so they rate their religiosity relative to some weighted average of the two. Their kids, in contrast, have normally only lived in one society. When asked, “How religious are you?” they naturally default to the standards of the only society they’ve ever known. This will be muted if they live in an immigrant enclave. But even then, the broader world is usually just a few blocks away. When a lifelong resident of Saudi Arabia says “I’m highly religious” it means something radically stronger than when his grandson who grew up in New York City pronounces the same words.

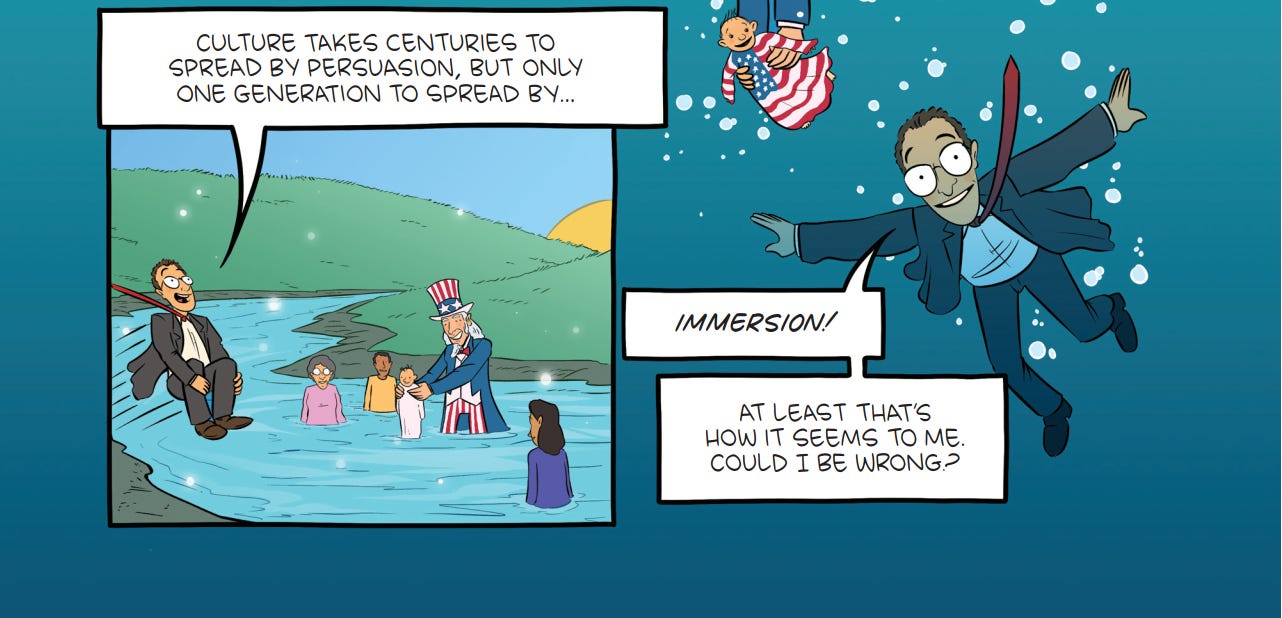

In The Culture Transplant, my colleague Garett Jones writes as if there is overwhelming evidence that assimilation is slow. So overwhelming, in fact, that you’d have to be a blind fool to deny it. I think his reading of the academic research is deeply wrong. But even if he were correctly summarizing what we know from the data, he’d be deeply confused about the actual facts about assimilation.

What are these “actual facts”?

First, if you compare first-generation immigrants to people from their countries of origin, they’re very different. First-generation immigrants proverbially do straddle two worlds. Yes, most seem very foreign to natives in their new country. But they also seem very foreign to friends and family from their original country! I’ve travelled all over the world, and met hundreds of first-generation immigrants in the U.S. My wife is a first-generation immigrant. I see with my own eyes that their assimilation, though far from complete, is high. If your eyes are open, you’ll see it, too.

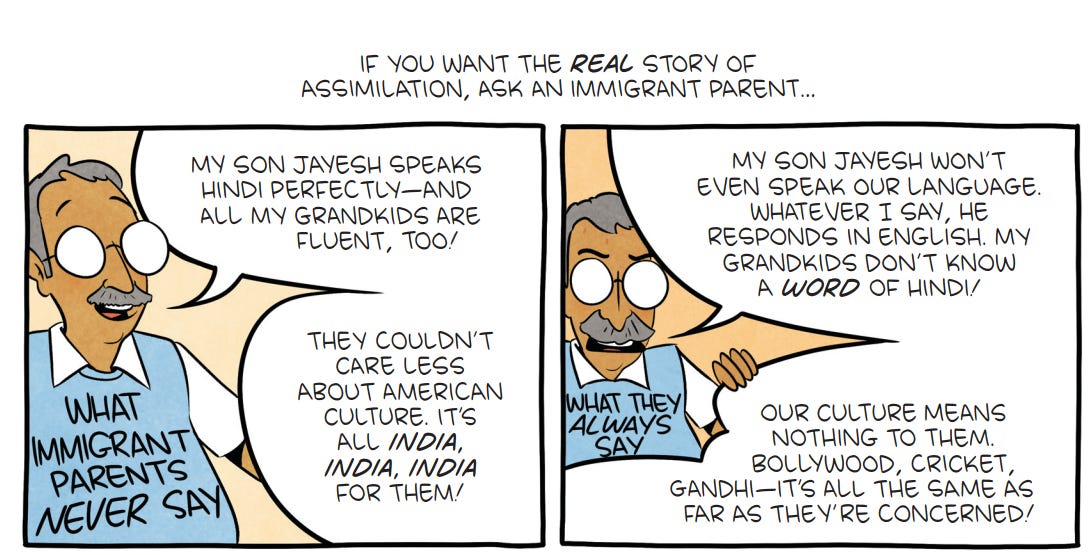

Second, if you compare the children of immigrants to their parents, they are very different. A contrast of night and day. Indeed, I’ve never met an immigrant parent who failed to notice that their kids had massively assimilated. Usually, though not always, to the parents’ dismay. And again, I’ve known many hundreds of second-generation immigrants. They’re some of the people I know best in the world. All four of my children are second-generation immigrants. If any of them still had one foot in Romania, I would know it.

If you want to quickly assess an individual’s assimilation, your best bet really is to listen to how they talk. If they can’t speak the local language at all, they’re probably not assimilated at all. If they speak the local language with a thick accent, they’re moderately assimilated. A mild accent? Highly assimilated. No accent? Then their assimilation approaches 100%. If you’ve met a lot of immigrants, you know this to be true.

Doesn’t academic social science trump piles of first-hand experience? Don’t be absurd. Academic social science helps us understand unfamiliar social situations. Academic social science helps us see the Big Picture. Academic social science helps refine our first-hand experience. But if academic social science directly contradicts massive first-hand experience, first-hand experience wins, because social science just isn’t that good.

The social science of assimilation, moreover, is especially weak. How weak? So weak that none of the scores of papers on the topic I’ve read seriously worried that self-reports automatically and severely understate assimilation. Indeed, I can’t recall any of them even mentioning the possibility.

There’s definitely truth here, but weighted towards certain kinds of immigrants. Most immigrants, illegal and otherwise, are from central and South America. Where there are massive pockets of immigrants from similar culture, assimilation is much slower. I know tons of second generation Latino immigrants whose grandparents came during the Cesar Chavez timeframe that speak Spanish. Where I live the billboards are in Spanish, the second place in this country, a couple thousand miles apart, where I’ve lived that Spanish has been the dominant language. I went to a diocesan-wide Catholic event yesterday where half the Liturgy was in Spanish. Eventually, assimilation will happen but it will happen much slower than for your kids.

Culture is necessarily a melting pot. When you add in small portions then that doesn’t impact the broader culture much. When you add in a huge portion from a very specific culture, in a short timeframe, that has an impact. Eventually, it will all meld into one but it’ll look much different. The Italians, Irish, and Germans had similar immigration waves which eventually melded into one culture but that culture did end up changed.

The impact isn’t necessarily bad. But I don’t think you can say there will be no impact. Small examples like Romanians are quickly assimilated because there is no existing presence of Romanians to slow it down. Indians are relatively small, already have English familiarity or fluency, and have generally arrived after being educated and ready to buy their way into nice neighborhoods.

The main cultural pressure from immigration is coming from Latinos who are arriving into existing neighborhoods of Spanish-speakers who help retain their culture into the next generation.

In general, it appears that Latino immigrants’ cultural values are close to mine than atheist lefties. I’m a bit worried about the tendency towards socialism in those countries, but I’m hopeful that there will be a bit of a Cuba effect where the ones disaffected with their old leftist government will be more likely to come here. Plus, the general selection effect of someone willing to risk it all for a better life.

But I don’t think you can say that there will be little to no effect on the broader culture.

My town has transformed in the last 15 years from being overwhelmingly white to being an almost even mix of whites, Indian immigrants, and Chinese immigrants. (Very very few Black or Hispanic people though). I have two kids, 7 and 11 in the public school system and the children of the Indian and Chinese immigrants are amazingly no different culturally than the children of the white parents. And when I say no difference, I really mean no difference. They may speak to their parents in their native language but other than appearance, there's really no way to tell the kids apart.