Chris Freiman, my friend and former Bet On It guest blogger, is an extraordinarily reasonable guy. He also supports the Universal Basic Income, which I regard as a terrible idea. Worse than the status quo! So I asked Chris to write another guest post defending his position. I’ll reply in the near future, then give Chris the last word if he wants it.

Here’s Chris:

I agree with Bryan that the right question to ask about a universal basic income isn’t whether it’s the best possible option but rather whether it’s better than the status quo. If we replaced the current welfare state with a UBI, would that be an improvement? I think it would be.

One major advantage of a UBI over the status quo is that it’s better for recipients. To motivate this idea, suppose your employer gives you the following choice: take your annual $1,000 bonus in cash or receive free lunches at the office with a total value of $1,000. Surely you’d take the bonus in cash. Why? Because if you want the lunches, you can use the cash to buy them. And if you don’t want the lunches, you can use the cash to buy something else.

Similarly, someone is better off receiving cash instead of what’s distributed to them by the welfare state because it gives them the flexibility to provide for themselves as they see fit. They can always use that cash to buy the bundle that the welfare state would have distributed to them or they can use it to buy something else that they value more highly. A UBI gives people the freedom to buy the quality and quantity of resources that they themselves deem appropriate for their particular circumstances. Beyond the freedom argument, “findings are generally positive that UBI-type programs alleviate poverty and improve health and education outcomes and that the effects on labor market participation are minimal.”

So what about the downsides? Bryan argues that the UBI is wasteful—if you were running your own charity, “you’d target spending to do the most good. And unlike the UBI, the status quo makes some effort to so target its resources.” I’ve got a couple of thoughts here. First, while the status quo does make some effort to target its resources, it doesn’t do a very good job. As Michael Munger points out in Tomorrow 3.0, welfare spending amounts to about $42,000 per family of three in poverty per year, which would be more than enough to lift them above the poverty line if it were distributed to them directly. So a lot of welfare spending simply isn’t reaching those who need it the most. Second, we can make a UBI progressive with adjustments on the tax end. It’s true that even Bill Gates will get a check—and that looks wasteful—but he’ll be paying far more into the UBI than he’ll be getting out. Plus, this consideration should help allay worries about the affordability of a UBI.

Bryan raises another concern about UBI’s lack of targeting—those who simply choose not to work will still receive money. And there’s a clear reason to worry about this: it will incentivize people not to work. In reply, I’ll first note that the status quo also generates incentives not to work. Bryan acknowledges this, but points out that “switching to a UBI would expand the familiar perverse effects of the welfare state to the entire population – including you. And if taxes rise to pay for the UBI, the population-wide disincentives are even worse.” However, a UBI will also improve incentives to work in some cases.

To take one example, replacing the status quo with a UBI would eliminate benefit cliffs. A recipient of a benefit faces a “cliff” when they’ll lose more than one dollar’s worth of the benefit upon earning one dollar of income; thus, someone facing a benefit cliff has a strong incentive not to earn that dollar of income. A UBI doesn’t create any cliffs—earning more money won’t reduce your benefits. Of course, it could be that a UBI creates worse incentives than the status quo, all things considered. Yet evidence suggests that we shouldn’t be too worried that a UBI will cause a dramatic drop in employment. As one overview of the effects of a UBI puts it, “The evidence from diverse interventions in low-, middle-, and high-income contexts indicates minimal impact on aggregate measures of labor market participation, with some studies reporting an increase in work participation. When reductions do occur, time is channeled into other valued activities such as caregiving.”

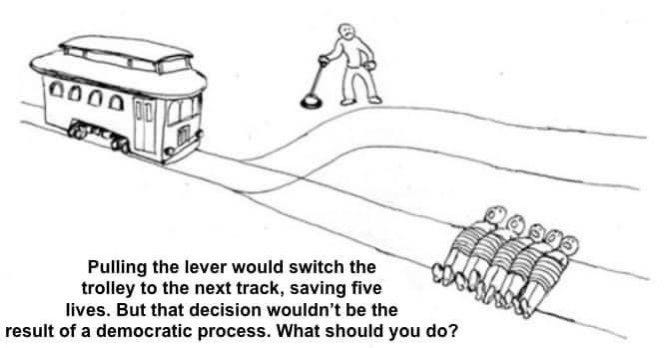

There’s a second reason to be concerned about a UBI’s lack of targeting. As Bryan writes, “Forcing people to help others who can’t help themselves – like kids from poor families or the severely disabled – is at least defensible. Forcing people to help everyone is not.” In brief, while taxing someone to help those unable to work may be just, taxing them to help the person who is perfectly able to work but would prefer to surf (to take an example from Philippe Van Parijs) is not.

What, though, should we do about the problem of the surfer? Presumably the way to address it is to restrict access to the money somehow. But this creates a new problem: restrictions will inevitably exclude some people who need the assistance along with those who don’t because they’ll create administrative burdens that make it more difficult to access the benefit.

Consider some examples. Work requirements might be imposed to exclude the surfer. But often recipients are unaware of the requirements and face difficulty establishing that they’ve met them. Disability requirements also create significant administrative burdens that reduce recipients’ access to benefits. The Earned Income Tax Credit is meant to help poor families, particularly those with children. But about 1/5th of eligible taxpayers didn’t claim it. While an unconditional income program will distribute money to some who shouldn’t get it, a conditional income program will fail to distribute money to some who should get it. So which should we opt for?

I favor the unconditional income program for two reasons. First, as noted above, evidence suggests that a UBI won’t prompt many people to drop out of the workforce to spend their days surfing. Second, and more importantly, it’s worse if someone who needs help doesn’t get help than if someone who doesn’t need help gets help. That is, it’s morally better if both the surfer and the child from a poor family receive assistance than if neither receive assistance.

What drives me nuts in this debate is that the US already has a universal basic income. It’s called Social Security.

Granted, it doesn’t take effect until you’re ~65, and there are some (fairly minor) restrictions. But it’s the closest thing we’ve got.

It’s also the largest item on the federal budget, soon to be bankrupt, and (from my personal observations) disincentivizes work and encourages early retirement, as well as a general attitude of entitlement from the government.

You could say that it’s not a very well designed program, but that’s the point. You don’t get to decide how a UBI is implemented, the existing federal government does.

Chris is effectively promoting that we get rid of the one saving grace of social security (the age limit), and promises that all of the clearly bad and negative consequences that we see with the existing system will just go away.

I find this highly implausible.

Are people poor because they don't have money or are they poor because they weren't raised properly to want and know how to provide for themselves? If you believe it's mostly the latter, UBI would help entrench and perpetuate the problem for generations to come. And UBI would foster an entitlement mentality: society owes me a living.

Once that mentality is in place, the amount is never enough. There will be constant conflict to ratchet it up. And almost nothing destroys people and societies as quickly as entitlement and dependency.

The current system has at least some features to treat assistance as a temporary safety net. That's a good thing.

Instead of UBI, why not increase the earned income tax credit and cut further on programs for the able-bodied but not working?