Knowledge, Reality, and Value Book Club: Huemer's Last Word, Part 1

Here’s Part 1 of Huemer’s last word on Knowledge, Reality, and Value.

Many thanks to Bryan Caplan for the extensive, thoughtful, and interesting discussions over the course of this Book Club. Thanks also to all the readers who contributed their thoughts. I found the discussion very high quality and serious.

Bryan’s comments below, preceded by “BC”, followed by my replies.

1) On consequentialism vs. deontology in the history of ethics:

BC: Why doesn’t the Ring of Gyges thought experiment count? At least one common interpretation of the debate is that we should practice justice as an end in itself, not because of its consequences. …

As I read it, Socrates is arguing over what is good, not over whether one should maximize the good. Note that holding that justice is intrinsically good doesn’t challenge consequentialism (though it does challenge utilitarianism), because it’s consistent with holding that you should maximize the good. To see what Socrates/Plato thought about consequentialism, you’d have to look at whether they thought it was okay to commit one injustice to prevent two similar injustices.

2) On the probability of the BIV hypothesis:

BC: Lower, definitely. But why “low”? In fiction, after all, the main use of the Brain in a Vat is to simulate reality. I still say that everything hinges on the high prior probability of the Real World story relative to all alternatives.

Let’s distinguish two skeptical hypotheses:

G-BIV (generic BIV hypothesis) posits only that our experiences are explained by scientists stimulating a brain.

S-BIV (the specific, stipulative BIV hypothesis) adds to G-BIV the assumption that the scientists stimulate the brain in exactly the same way that a typical brain in the real world would be stimulated.

If G-BIV and RWH (the real-world hypothesis) have comparable initial probabilities, then G-BIV is going to have a much lower posterior probability in the light of our evidence. Equivalently: S-BIV has a much lower prior probability. This is because in the absence of evidence, we start from the principle of indifference, and the vast majority of the ways of stimulating a BIV would not result in a perfect replication of normal, real-world experiences.

Perhaps a better way to think of it is to consider hypotheses about the capabilities and motives of the scientists. Only a tiny range of possible capabilities and motives, out of all the possible ones that a troop of BIV-owning scientists could have, result in their producing a perfect simulation of a normal, average life.

Regarding fiction: The reason why fictional stories (e.g., The Matrix) invoke perfect simulations of normal life is not that that is likely (even conditional on having a BIV or similar apparatus), but simply that that makes for a good story.

3) About recognizing shapes made by intelligent agents:

BC: Not heart shapes specifically. I’m thinking of the independent knowledge that so far, things that look like carvings have always been man-made. If that sounds circular, I say it’s just the problem of induction all over again.

“Looks like a carving” sounds to me like it presupposes a sense of what kinds of things are likely to have been created by intelligence, vs. what things are likely natural – that sense is what the Argument from Design proponents are invoking, which I took you (Bryan) to be rejecting.

Not sure what you’re suggesting about the problem of induction. Maybe that circularity is okay because a circular response to the problem of induction is okay? I would deny that circularity is okay, even with respect to the problem of induction. See my paper on induction, which gives a non-circular solution: http://www.owl232.net/papers/explanation.pdf.

BC: How about a sphere? It’s awesomely “ordered.” Perfectly symmetrical…

It is ordered, but it’s a simple order, so it’s not hard to imagine simple, unintelligent mechanisms that bring it about. Like the force of gravity, or surface tension.

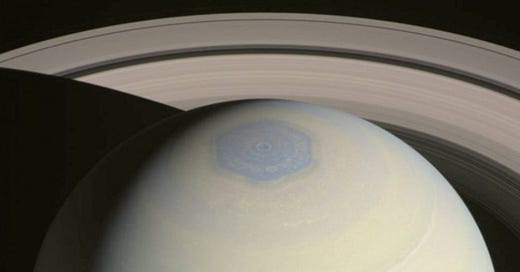

Here is a better example of something that looks artificial (but isn’t): I recently learned that there is a giant hexagon on Saturn, made of atmospheric gases. The hexagonal shape makes it much weirder than if it were simply round. Scientists aren’t sure why this exists, but there are some theories.

It’s pretty weird, but it’s still a much simpler order than, say, a living organism.

4) About setting the parameters of the universe:

BC: Well, we’ve looked around the universe a lot, and never seen anyone “setting its parameters.” We haven’t even found a securely locked control panel with a “parameters of the universe” label. And the very idea sounds totally fanciful, so we should assign it an ultra-low prior probability.

About the prior probability: I think the “sounds totally fanciful” reaction is specific to atheists. The vast majority of people have thought that there were supernatural beings with all kinds of awesome powers. Most today believe in a creator of the universe. I don’t have a lot of data on their psychology, but I suspect that most find it intuitively plausible that someone created the universe.

About the evidence: If there was such a creator, I don’t think we’d particularly expect to see that person doing His work, since we wouldn’t be around until after He created the universe. I don’t think we’d expect to find a control panel either, even if we looked around a lot.

I also don’t think we’ve really looked around the universe a lot. We’ve looked around the Earth a lot (and even then, mostly just the surface), but the observable universe is about 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times larger than the Earth, to say nothing of the unobservable parts of the universe, if such there be. We’ve also been around for perhaps one 46 thousandth of the age of the observable universe. I think there’s lots that we don’t know, especially about questions like the origin of the universe.

5) On the “Made by God” example:

BC: My bad, I missed the latter stipulation. But then it’s practically circular, because anything that’s a “consequence of the laws of nature” is by definition not human-made (or even alien-made).

I don’t see a circularity problem. The example is just an illustration of a point about the Fine Tuning Argument. The example shows that you could have cases in which you should conclude that (aspects of) the laws of nature were designed by an intelligent (non-human) being. It’s okay that the example stipulates that the thing we observe is something we know humans couldn’t do, because that is also true of the evidence in the actual Fine Tuning argument.

I gave this example because some of the objections to the FTA actually imply that even in the “Made by God” example, even with the stipulation that the observed evidence is a consequence of the laws of nature, you still would have no reason to believe in God, or any other form of intelligent designer. This is a reductio of those objections.

6) On the improbability of a life-supporting universe:

BC: It’s only “extremely improbable” if you think the parameters of the universe could have been “set differently.” And as I said, that seems totally fanciful to me. There’s no sign that a cosmic control panel exists.

This is one of the objections that implies that, even in the “Made by God” example, you still have no reason at all for believing in any form of intelligent design; you should just shrug your shoulders and say, “That’s just the way it is.” Any such objection must be mistaken.

In this case, the mistake is the assumption that, in order to assign (non-extreme) probabilities to propositions about the laws of nature, one has to first be convinced that the laws were set by someone (or something?), or can be changed. One need not assume either of those things merely to have a non-trivial probability distribution.

7) On what is “fantastical”:

BC: What distinguishes all these cases? (a) We only hear about the fantastical stuff from unreliable sources or in fiction; the other stuff we either see first-hand or hear about from reliable sources. (b) The fantastical stuff appeals to the human emotion of wonder; the other stuff is boring by comparison.

This would be an apt response to arguments based on testimony about miracles. The unreliability of the sources would be a reason not to accept those arguments. But I don’t think it’s a reason to deny the existence of God; rather, it means that the testimony is merely, at worst, irrelevant.

Regarding the emotion of wonder, I think that could be a reason for discounting some stories that have been handed down – they could have been transmitted because of the desire for amazing stories, even if they were not true. It might also be a reason for discounting intuitions of people who have a particular passion for wonder, because that passion could be biasing them.

However, none of this is actual evidence against the existence of an intelligent designer; it just means one should discount some putative reasons in favor. I also don’t see how it shows that the prior probability is low. As a conceptual matter, if you’re citing evidence, then you’re talking about a posterior probability, not a prior probability.

About the Fine Tuning Argument: fortunately, it doesn’t rely on unreliable testimony. The empirical premises come from modern astrophysics. The fact that some other people who are unreliable also support a somewhat similar conclusion for very different reasons doesn’t count as evidence against this argument being correct.

I would say, by the way, that whatever the origin of the universe is, I think it is bound to be something strange and amazing. The standard Big Bang theory is amazing already, as are many things in modern physics.

8) Do incentives affect your degree of free will?

BC: By the logic of your alcoholic story, it seems like the more money we offer the condo owner, the “less free” he is to turn it down. That seems bizarre to me. I say you are fully free to reject a billion-dollar offer on your condo. And the alcoholic is totally free not to drink.

The alcoholic has a psychological compulsion or other disorder, which is normally not present in a condo owner considering a purchase offer. The condo owner, in the normal case, also won’t have any of the other sorts of psychological conflicts that would reduce freedom. So for the condo-owner, it’s plausible that he’s fully free regardless of the incentives.

To make the alcoholic analogous to the condo-owner, we’d have to add some stuff to the condo story. Like he’s got some kind of psychological compulsion to accept all purchase offers. Or maybe he’s got a conflict between immediate inclinations and his rational judgment. Or something like that. In that case, I think it is plausible that he’s going to be less free for some larger offers than for a ridiculously low offer. But this example is now so similar to the alcoholic case that I don’t expect it to help resolve the issue for anyone – you’ll either intuitively agree with me about both cases, or intuitively disagree about both cases.

The post appeared first on Econlib.