Remember Kahneman and Tversky’s Tale of Linda the Bank Teller?

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

Linda is a bank teller.

Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Logically, the answer has to be (1). After all, all feminist bank tellers are bank tellers, but not all bank tellers are feminists. Yet experimental test subjects routinely deny this: “More than 80 percent of participants chose option 2, regardless of whether they were novice, intermediate or expert statisticians.” Researchers call this the “conjunction fallacy,” because it defies a basic law of probability:

The probability of two events occurring in conjunction is always less than or equal to the probability of either one occurring alone. Compare the Linda case to the following case: what is more likely: that (1) you will have a flat tire tomorrow morning or that (2) you will have a flat tire tomorrow and that a man in a black car will stop to help you out. In this case, it should be evident that (2) is not the most likely outcome.

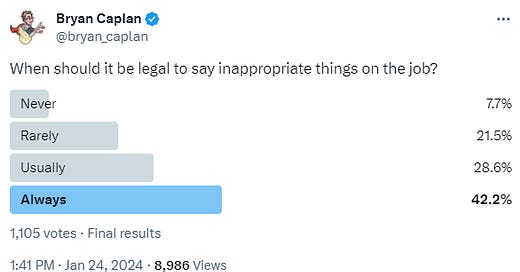

I recently decided to redo Kahneman and Tversky’s original experiment on Twitter, using two much more controversial questions. I started with a general inquiry about workplace free speech.

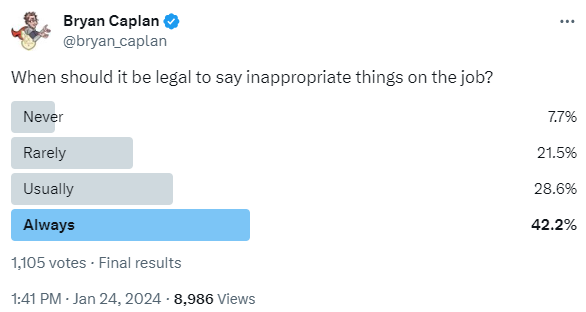

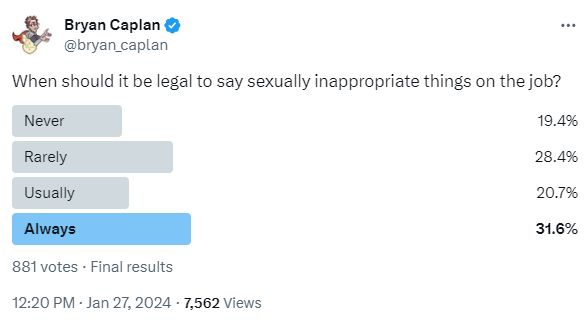

A few days later, I switched to an analogous yet more specific question about workplace free speech:

As you’d expect given my libertarian following, “Always” wins both surveys. Yet as you’d expect given our modern Zeitgeist, “Always” is a minority position. What’s really striking, though, is the logical incompatibility of the results. People are markedly more likely to say that it should always be legal to say inappropriate things on the job than they are to say that it should always be legal to say sexually inappropriate things on the job. But saying sexually inappropriate things is a subset of saying inappropriate things!

While my paired results fit the conjunction fallacy, they also fits earlier research on support for free speech. In the abstract, almost everyone endorses “free speech.” In 2007’s State of the First Amendment Survey, 98% (!) said “the right to speak freely about whatever you want” was essential or important. Yet in the same survey, 44% strongly disagreed that, “People should be allowed to say things in public that might be offensive to racial groups.” “Might be”!

Results for free speech generalize much more widely. Spending cuts are very popular in general, but almost every specific spending cut is unpopular. Deregulation, too, is highly popular in general. From 1985 to 2016, only 20% of respondents in the General Social Survey have actually opposed it. Yet almost every specific regulation pollsters have asked the public about enjoys strong support.

What’s going on? Here are three stories, each of which seems partly true. (Feel free to weigh them in the comments).

Kahneman and Tversky normally just insist that most humans are bad at formal logic. And they’re not wrong.

Many philosophers, in contrast, will emphasize that most humans are prone to bold overgeneralizations, but bad at generating counterexamples for themselves. A big part of “thinking like a philosopher” is learning how to craft such counterexamples.

At least in Western societies, “freedom” sounds very good. Unfortunately, what people will actually choose to do with their freedom often sounds very bad. And as I keep telling you, people usually favor whatever policy superficially sounds best. The freedom that we retain heavily hinges on getting people to hastily endorse freedom in general, then changing the subject before they realize what they’ve signed up for.

I say all of this even though I am convinced that our specific judgments are usually much more reliable than our general judgments. Strangely, most of the value-added of economics is discovering that — when comparing markets versus government — it is our specific judgment that is deeply impaired.

“Freedom for Linda the Bank Teller?”

“Great!”

“Including the freedom to work for any mutually agreeable wage?”

“No, there has to be a minimum wage.”

“What if this keeps Linda from finding a job?”

“Huh?!”

Fascinating Bryan! I do wonder about some specific differences between Kahneman & Tversky and your experiment, though...

K&T forced on the same group of people two choices which clearly prove the fallacy: since p(bank teller) = p(bank teller & feminist) + p(bank teller & non-feminist), there's no way that p(bank teller & feminist) > p(bank teller)

In your question there's the possibility that the responders are different (plus all other weird human factors such as answering before or after lunch etc), but more interesting to me is the looseness of language and associated interpretations.

Let's say that in general people don't interpret "inappropriate things" as "all and any inappropriate things, no matter which type," and/or also that "always" is not interpreted as "absolute 100% with no rounding", but instead something like "95% of the time or above"

Then if "sexual inappropriate things" is seen as a small-size sub-segment of "inappropriate things" with stricter control agreement whereas "non-sexual inappropriate things" is a much-larger sub-segment with much looser censorship support, that might provide an alternative logical explanation. (edit: by way of weighted averages)

Not that I think that's the most likely reasoning path! Probably the emotional / gut-feeling path is the winning explanation. But just something to consider.

Love reading your blog, thanks for the continuing intellectual challenges!

I think, to some extent, a large part of the issue with these questions is that people are answering the question *they think you are asking*, not the question *you think you are asking*. In order to answer the question, first they have to figure out which of the various interpretations of the question you might be asking, which involves building a model of you, and asking what information you are trying to ascertain - and critically, here, the answers are information used in building that model.

So, in the Linda example, that you have provided additional information in choice B gives additional information about A. They are not considered in isolation, because the first task a person's brain has to deal with, in interpreting the question, is figuring out who you are and what you are trying to ask. Since social justice comes up in the question, and feminist comes up in one of the answers, they guess that you're asking whether or not Linda is likely to be a feminist, -not- whether Linda is likely to be a bank teller. So they kind of mentally add an implicit "... and is not a feminist" to answer A, in order to make sense of the bizarre question you are asking. Once they do this, the question makes sense to them, and so they can complete the question by answering it. (In a sense, the two "bank teller" pieces of information in the answers cancel out as red herrings; unless you're familiar with formal logic, you have no experience with these kinds of questions, and so cannot understand what is being asked without spending a lot of time thinking about it.)

Remember: A person answering your question does not know what you are asking, they have to figure that out. The first step in answering a question must be figuring out what is being asked, and this additional pivot point creates a lot of apparent chaos in the final answer.

If you include this process in interpreting polls like this, a lot of them will make a lot more sense. The freedom case, for example, kind of trivially washes out: A lot of people are not, in fact, interpreting the second question in a sense that makes it a subset of their interpretation of the first question. In particular you likely have some group of people who are interpreting your answers in a temporal fashion (look at all the temporal words in your question and your answers - you've literally asked "when", when you meant something like "Under what set of circumstances"). Similarly, you probably have a group of people who are answering with a particular notion of "inappropriate" which may not be a proper superset of "sexually inappropriate" - and some other group of people, who may be interpreting "inappropriate" in the manner you expect, may be interpreting "sexually inappropriate" in a manner you -don't- expect.

For example, "Sleep with me or you're fired" - is this strictly speech, or is it something more? I'm not sure whether or not it would be included in "saying inappropriate things" by your definition, but it does seem like it could plausibly be included in "saying sexually inappropriate things" to a much greater degree, and I'm more confident in it being placed in that bucket than I am in it being placed in the theoretical superset. There's some kind of uncertainty principle in language, where greater specificity on one axis can force less specificity on another.