Maximum Progress on Progressivism

Huemer's *Progressive Myths* is the best book on wokeness

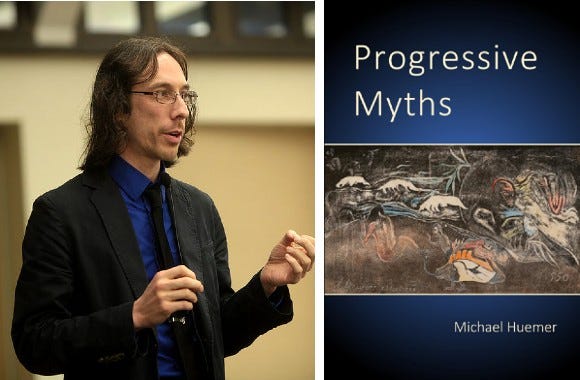

If you are not yet a fan of Michael Huemer, you should be. Hyperbole is the worst thing in the universe, but I still affirm the following:

Huemer’s The Problem of Political Authority is the best book on political philosophy.

Huemer’s Ethical Intuitionism is the best book on meta-ethics.

Huemer’s Knowledge, Reality, and Value is the best introduction to philosophy.

And now to this list of superlatives, I add: Huemer’s new Progressive Myths is the best book on wokeness.

The quality of Progressive Myths is evident right from the introduction.

I will not give a neutral presentation in the following chapters, but I do aim to give an objective presentation. I am a philosopher, not a lawyer or a campaign manager. My task is not to replace left-wing propaganda with right-wing propaganda. My task is to replace propaganda with a fair and accurate account. Hence, though the myths herein are chosen for being incorrect in some way, I will mention when I think there is something in the vicinity of the myth that is correct…

The myths I address herein are about relatively circumscribed, objective points of fact. I do not address such big-picture issues as “Can socialism really work?” or “Is wealth inequality unjust?” Those sorts of questions would take much longer to address, and it is difficult to answer them decisively. Instead, I address simpler questions such as, “Do women really earn 30% less than men do for the same work?”, because there we are much more likely to make actual progress.

And you have to love Huemer’s humble request near the end of the intro:

I have one request for readers, whether you are left-wing, right-wing, or other. Please do not make up views that I didn’t assert and ascribe them to me. Do not assume that I am a stereotypical “right wing” extremist or that I agree with right wing people where I haven’t explicitly said so. (I have found, by the way, that leftists tend to be extremely bad at understanding what rightists think anyway.) Do not “read between the lines” to infer what I “must be implying”. If you think of some ridiculous or horrible political view that you think I’m implying, that is almost certainly just in your imagination. I am not the sort of writer who likes to imply his point.

The rest of the book calmly criticizes common progressive beliefs about “relatively circumscribed, objective points of fact.” He starts, much to my surprise, with five chapters about five specific people who are “infamous for being infamous.” Kyle Rittenhouse is one of the five. Huemer exculpates all five. Why bother with this trivia? Because it exposes deep epistemic corruption of what Alex Epstein calls our society’s “knowledge system.” Huemer again:

If you didn’t follow these cases, you may wonder why these cases are important for understanding our society. The answer is that these are case studies in the sort of distortions found in prominent information sources. These cases are particularly useful because it is usually more straightforward to determine the truth about a single episode than it is to determine the truth about some generalization about society. Once we see how media and activists treat relatively straightforward matters of fact, we will know better how to receive their claims about more complex issues.

Ever mindful of confirmation bias, Huemer finishes this section with a chapter on “Three Non-Myths,” leading with “The correct conclusion is neither ‘Police are always in the right’ nor ‘Police are always in the wrong.’ The correct conclusion is ‘One must examine the facts of each individual case.’” The chapter ends with George Floyd, where Huemer’s verdict is: “Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd accidentally but culpably.”

Next, Huemer turns to the broader question of “Racial Myths.” However you slice the data, police shootings of unarmed blacks are ultra-rare: 36 for the entire United States in 2019. Perspective:

It would not be shocking if, of 47 million black people, a total of 36, despite being unarmed, did something sufficiently threatening to cause them to be killed by police. In any case, the risk of this happening to a given black person is extremely small; they are literally more likely to be struck by lightning.

A disproportionate share of people shot by the police are black, but the same is true for males. In both cases, the key question is “Why?” And in both cases, the answer is almost monocausal: Because both groups commit a disproportionate share of crime.

After reviewing several more myths about racism, Huemer turns to myths about sexism. He handles the gender pay gap like a well-trained economist — yet he’s not shy about citing Warren Farrell. He also criticizes broader notions of sexist harm like, “Maybe sexism causes women to value money less than men”:

Just focusing on the possible cultural component, perhaps men are conditioned to value financial success more, relative to other life goals. One could interpret this as indicating that society values men’s interests more and therefore cares more about their financial success. But one could just as well interpret it as indicating that society values women’s interests more and therefore cares more about their personal fulfilment.

I especially enjoyed the “Women Don’t Lie” chapter, which carefully examines some advocacy statistics on false rape accusations. Despite desperate defenses, #BelieveWomen really is a preposterous slogan. Huemer quotes Biden’s “From the very beginning, I’ve said believing women means taking the woman’s claim seriously when she steps forward, and then vet it. Look into it,” and responds:

Pace Joe Biden, “believe x”, in English, does not mean “look into it”. (Admittedly, “Don’t automatically disbelieve women” is a less catchy slogan than “Believe women”.) One might as well claim that “Lock up Joe” means “Give Joe a fair trial.”

As a philosopher, Huemer is well-positioned to explain where “false accusation” statistics come from:

How could researchers know what percentage of rape accusations are true and what percentage are false in a particular sample? Wouldn’t that require having some sort of crystal ball to see what really happened in each one of these cases?

Suppose a woman accuses a man of rape, and the man denies it. There are no other witnesses and no physical evidence. How would scholars figure out whether this was a true accusation or a false one? The key lies in redefining the word “false”. In Lisak et al.’s article, “false report” does not mean “report that isn’t true”. It means roughly, “report that was proven not to be true”. That is, a “false report” is one such that the accuser admitted that she was lying, or other similarly clear evidence showed that the events she reported definitely did not happen. If it was never determined whether the events happened, the report is not “false”. So the sort of “he said, she said” case described in the preceding paragraph would be deemed non-false. That covers a large portion, perhaps half or more, of all cases.

Now that we know what we’re talking about:

What is the actual rate of false rape accusations, then? No one knows. It is at least 2-10%, but it may be much more. In Lisak et al.’s study, police found insufficient evidence to proceed with the case 45% of the time. There is no way of knowing how many of these were in fact false accusations. In another 35% of cases, the police proceeded with the case, which probably means that most of these were true accusations. Finally, there were another 14% of cases about which we can say nothing because the case file was incomplete. So we can say with confidence that the false accusation rate was somewhere between 6% and 80%.

Several people I know were disturbed that Huemer has a section on “Environmental Myths” that includes two chapters on climate change. But if they actually read his words, they’ll discover a deeply reasonable discussion of two specific points. First, though there is a strong expert consensus view that man-made climate change is a serious problem, this consensus is, contrary to the media and activists, far from unanimous. Second, and more importantly, there is a strong expert consensus that man-made climate change is not anything close to an “existential risk”:

What sort of consequences do mainstream scientists expect from global warming? Ocean levels are expected to rise by 0.4-0.8 meters by the year 2100. This will not submerge New York City (as some alarmists in the media imagine); it will, however, slightly increase the risk of flooding in coastal cities.

The IPCC projects that an excess 250,000 people will die annually worldwide due to climate change by mid-century due to increased heat, undernutrition, and disease. That will be out of an expected total of 92 million deaths per year from all causes by that time, so global warming will account for about a quarter of a percent of the death rate. A more pessimistic study suggests that excess deaths due to global warming could increase to 2 million per year for the second half of the century.

Among the more alarming projections is one claiming that, if left completely unchecked, global warming could cause as many as 73 deaths per 100,000 population per year by 2100, which would make it comparable to the current death rate for infectious diseases. (For an expected population of 10 billion by 2100, that would mean 7.3 million deaths per year.) Economist William Nordhaus, a leading expert on the impacts of climate change, estimates that global warming will have costs on the order of 2.5% of total world GDP by the end of the century.

The last section of Progressive Myths zooms out to ask bigger questions. A few highlights include…

The thinly-veiled agenda of DEI statements:

No conservative could honestly write a statement that would get past the DEI screeners. Right-of-center thinkers are already a tiny minority of the academy, but in the next few decades, if woke administrators have their way, non-leftist voices will be completely eliminated from the academic world, and college “education” will consist of pure ideological brainwashing. This will not be an unintended side effect of programs to increase “diversity”; this is precisely what woke activists want. They want complete, unquestioning submission to every element of their ideology, from every single person in the academic world. Such is their commitment to diversity.

The function of the notion of “white fragility”:

Notice that white fragility, in DiAngelo’s reckoning, includes virtually any response other than saying, “Yes, Robin DiAngelo, you are correct.” If someone argues with DiAngelo, or remains silent, or declines to talk to her, all those indicate white fragility, which is bad because it perpetuates racism. So virtually the only way to not support racism is to agree with whatever DiAngelo says. It never occurs to her that the reason people react defensively to her could be that she is attacking them unfairly.

The big meta-lesson:

What should we do to avoid the harms of political myths? My central advice is obvious, but I will say it anyway. The main thing we should do is to be a lot more skeptical. When you hear some politically relevant information, ask yourself whether this is the kind of information that plays to a particular ideological orientation. Would you expect this, say, to be shared only by conservatives, or only by progressives?

If the answer is “yes”, you should immediately be skeptical. Do not presume that it is honest content; presume that it is deceptive until proven honest…

I cannot cover all political myths or even all progressive myths; however, the myths discussed above are, I believe, not atypical. Persuasive political content that is transmitted in the popular culture is almost always deceptive—oversimplified at the very least, often omitting crucial details that would reverse the conclusion you would naturally draw, and sometimes founded on outright lies.

Coda: To repeat, I deem Progressive Myths the best book on wokeness. Tyler Cowen, in contrast, is dismissive: “Michael is a very smart philosopher, but this book seemed like a waste of time to me. Will it persuade anyone? Do we need Michael writing seven-page essays rebutting various claims of the BLM movement and the like?”

Here is my response to Tyler.

Huemer’s book will be highly persuasive to any reasonable human, including reasonable humans who initially disagree with his thesis. That’s the maximum that an intellectually honest thinker can accomplish on a controversial topic.

Tyler misses the broader point of the book. Huemer’s not merely debunking specific woke claims. He teaches readers how to analyze confusing, emotional issues in order to reach objective truth — and how to avoid embracing the new woke myths that will arise in the future. Progressive Myths trains readers to resist media bias in a fundamental way.

Would an epistemically exemplary book on wokeness be worthwhile writing? Given the cultural power of wokeness, it’s hard to say No. Do any pre-Huemer books on wokeness qualify are “epistemically exemplary”? Given the oppositional culture of the right, it’s hard to say Yes. Progressive Myths is the epistemically exemplary book on wokeness that the world badly needs. And the prose is a joy to read.

Back in 2017, Tyler wrote a short piece on BLM stating: “My views are pretty simple, namely that I am a fan of the movement.” Please read his whole post. All I can say is: Hopefully Tyler has changed his mind since. If he hasn’t, he really should re-read Progressive Myths and be persuaded. It will be time well-spent.

“I am not the sort of writer who likes to *imply* his point.” A priceless sentence!

I don't know, this is coming awfully close to veneration.