In November, I chided Austrian economists for neglecting the John Haltiwanger’s empirical work on creative destruction:

Around 2000, I discovered that John Haltiwanger, a very mainstream economist, had a pile of empirical evidence vindicating the importance of Schumpeterian creative destruction. That pile is now a mountain. At the time, I tried to get Austrians to start reading Haltiwanger and his co-authors, but as far as I know, they never listened. Still, you could say that I’ve moved toward an Austrian view of entrepreneurial progress, and that’s a kind of convergence.

A few weeks later, Brian Albrecht of Economic Forces wrote a detailed response, which he’s kindly given me permission to reproduce in full here. I’ll respond in the coming weeks.

In a recent post reflecting on Austrian economics, Bryan Caplan mentioned that around 2000, he “discovered that John Haltiwanger, a very mainstream economist, had a pile of empirical evidence vindicating the importance of Schumpeterian creative destruction” and wished more Austrians would engage with this empirical work.1 I couldn’t agree more because this empirical work helps us understand and measure the competitive process.

Instead of Schumpeter, I will focus on Israel Kirzner, who also offered a radical view (at the time) of competition. Rather than focusing on market structure or the number of firms, Kirzner emphasized entrepreneurial discovery. Entrepreneurs are alert to opportunities; they discover price discrepancies and profit opportunities that arise from market disequilibrium. This discovery process is what drives market competition.

What does this discovery process actually do? It moves resources from lower-valued to higher-valued uses. Entrepreneurs identify better ways to deploy resources. Some entrepreneurs spot pure arbitrage opportunities, like price differences across markets. That’s more of a pure Kirznerian entrepreneur. Others discover new production methods or products that create more value from existing resources. That’s more Schumpeter. Both types of discovery improve how the economy uses its resources.

But how would we measure whether this process is working? If Kirzner is right, we should see a constant reallocation of resources as entrepreneurs discover better uses. This reallocation should systematically move resources toward more productive firms and uses.

We can actually measure the first part—reallocation. And in the US, we have immense reallocation. In just October 2024, US businesses hired 5.3 million new workers while separating with nearly as many. How do we know that? Haltiwanger and collaborators helped develop key data sources like the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), along with other data on dynamism and reallocation, such as the Longitudinal Business Database. Before these datasets, economists lacked systematic evidence of the incredible amount of churn beneath seemingly stable aggregate employment numbers. By tracking individual establishments over time, these data revealed the extent of job creation and destruction that characterizes a dynamic economy.

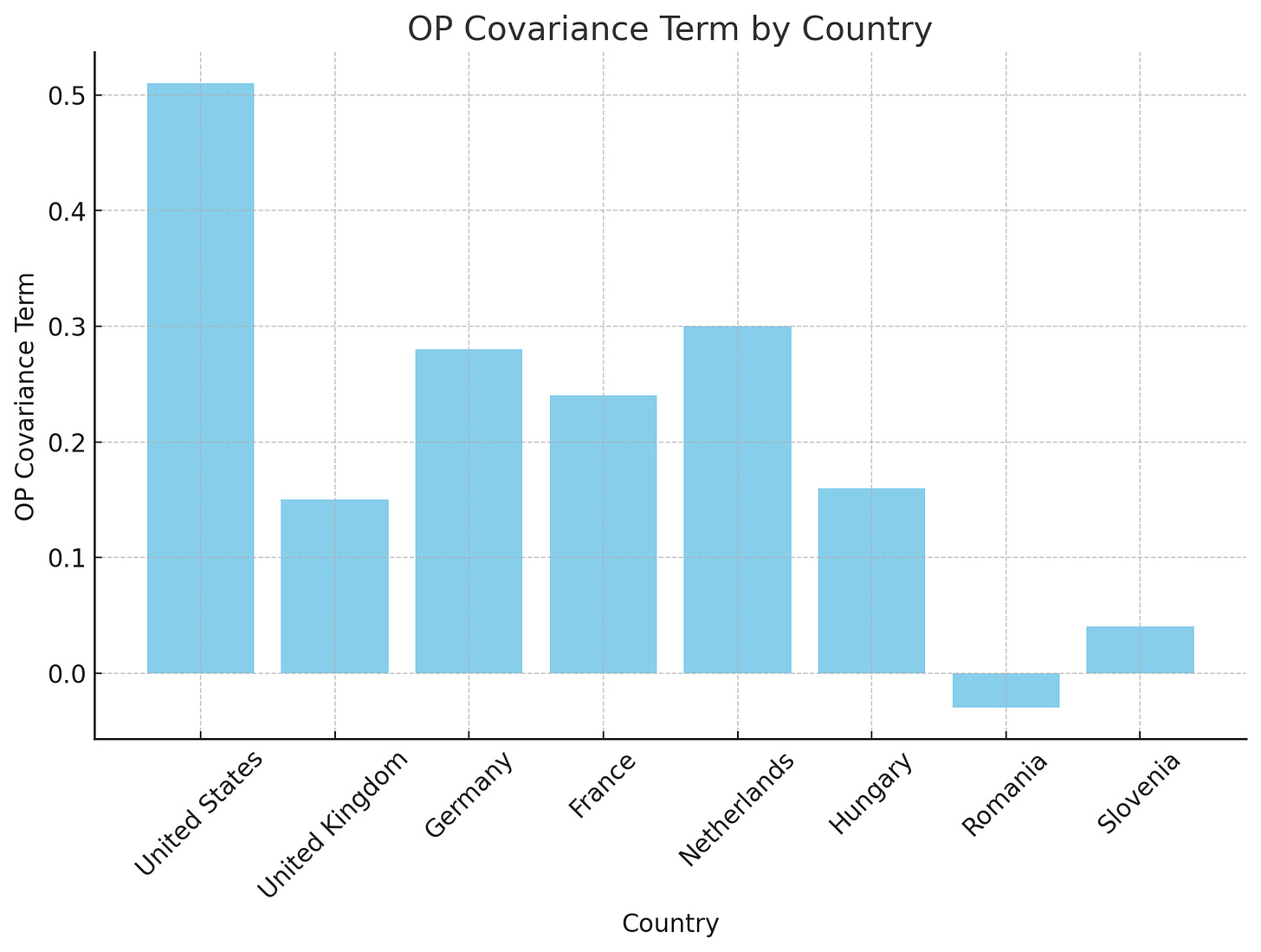

The harder part is measuring whether this reallocation improves resource use. Is all this churning actually helping? Are some economies doing a better job of harnessing Kirznerian entrepreneurship? I’ve argued that one approach could from what’s called the Olley-Pakes decomposition. This breaks down market-level productivity into two pieces:

Total Market Productivity = Average Productivity + Covariance(Market Share, Productivity)

That covariance term captures whether more productive firms gain market share over time. When there’s a strong positive correlation between efficiency and market share, it indicates resources are being reallocated toward their highest-valued uses—exactly what Kirzner described as the entrepreneurial market process. That’s why I’ve argued that this covariance term should be thought of as a measure of competition.

Bartelsman, Haltiwanger, and Scarpetta showed the first systematic evidence that the US was better at this than other countries.

Haltiwanger and coauthors have also shown more about reallocation, which Austrians should appreciate, in particular. For example, Eslava, Haltiwanger, Kugler, and Kugler study trade, labor, and financial market reforms in Colombia during the early 1990s. They also see an increase in the market reallocation toward efficient firms. Bartelsman, Haltiwanger, and Scarpetta found the OP term was negative in many Eastern European countries in the 1990s (less productive companies captured more of the market). That turned around after market reforms and the move away from communism. In the Colombia case and the Eastern European case, we have systematic evidence that the reforms harnessed more Kirznerian entrepreneurship.

Speaking of Schumpeter—while he’s often contrasted with Kirzner, the empirical work suggests their insights are complementary. Schumpeter emphasized creative destruction—the process by which more innovative firms drive out less productive ones. Kirzner focused more on arbitrage and the discovery of existing opportunities. However, in practice, both processes show up in the data as reallocation toward more productive firms. The measures capture parts of both mechanisms.

Do these dynamism measures capture everything about Kirznerian, let alone Schumpeterian, entrepreneurship? Of course not. But it gives us a systematic way to measure whether markets are working like Kirzner described—moving resources toward more productive uses through entrepreneurial discovery. That’s obviously not true of all economies, so we don’t have any a priori way of knowing which ones are doing a good job. The key connection I’d make between Haltiwanger and the Austrians is that successful entrepreneurial discovery should show up as systematic reallocation toward higher-productivity firms. If entrepreneurs are spotting and exploiting opportunities, we should see market share flowing to those who create more value from resources. The measures aren’t perfect, but they let us quantify whether markets are actually working as processes of discovery and reallocation rather than static equilibria.

My attempts to bridge the gap

If I can shamelessly self-promote some more, my own research tries to bridge the gap between the Austrians and Haltiwanger.

My work with Ryan Decker (a coauthor with Haltiwanger) looks at the relationship between measures of market power, like markups, that are often seen as a lack of competition and business dynamism at the industry level. Most people think market power is rising in the US and dynamism is falling. Both are bad signs for the state of competition. Rather than focus on aggregate trends, we dig into whether industries with rising markups see the kind of declining dynamism that signals reduced competition.

What we found challenges conventional wisdom about market power. Industries with the highest increases in markups saw the smallest decline in dynamism. The two measures of competition point in opposite directions.

But this is perfectly plausible through a Kirznerian lens: markups and profits can reflect successful entrepreneurial discovery rather than harmful market power. When firms find better ways to serve customers or lower costs, they can charge higher markups while growing market share. This is exactly the reallocation toward more productive firms that characterizes healthy market competition.

But measurement alone isn’t enough—we need models to clarify the connection between entrepreneurial discovery and market reallocation. Many of those have been developed by non-Austrian economists, but the bridge could be more explicit. Along with Rafael Guthmann, I’ve been developing models showing how entrepreneurial discovery drives market-wide reallocation. In our simplest model, we start with two “islands,” with separate markets that don’t know about each other. When entrepreneurs discover the price discrepancy between islands, they engage in arbitrage.

This isn’t just moving to a new equilibrium through some mechanical price adjustment. The equilibration happens through active entrepreneurial discovery and competition. As more entrepreneurs discover the opportunity, they compete to capture it. Profits get competed away not through a tâtonnement process but through replicated discovery and entry. All of this can be captured in a formal model, which again bridges the gap with non-Austrians.

Kirzner emphasized that entrepreneurs are alert to opportunities; they discover price discrepancies and profit opportunities that arise from market disequilibrium. Through arbitrage and innovation, entrepreneurs help move resources from lower-valued to higher-valued uses. This process of discovery and reallocation drives markets toward a better use of resources.

That’s a long way of saying that Caplan is right. Austrians should read more Haltiwanger. And other economists, especially those interested in business dynamism, could benefit from reading more Austrian economics. By focusing on reallocation rather than structure, we can better understand and measure how market competition actually drives prosperity and progress.

Good piece. Nice to see Kirzner get some credit. I read Competition and Entrepreneurship... ouch, 42 years ago. "Speaking of Schumpeter—while he’s often contrasted with Kirzner, the empirical work suggests their insights are complementary." Yes, that seems right to me. Keep bridging the gap, Brian.

It should be noted that Bob Murphy of the Mises Institute has also responded to some of Bryan's recent postings:

https://mises.org/podcasts/human-action-podcast/responding-bryan-caplans-continued-critique-austrians