Abundant adoption and twin studies find minimal long-run nurture effects. In plain language: The family that raises you has little effect on your adult outcomes. A key caveat, though, is that almost all of these studies come from the First World. Does growing up elsewhere durably stunt personal development? Existing evidence is largely silent.

While reading the National Academy of Sciences all-new report on The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, though, I finally encountered some relevant data – though unfortunately, it only allows us to measure the effect of growing up in the U.S. versus anywhere else.

Background: To estimate an immigrant’s long-run fiscal effect, you must also estimate how successful his descendants will be. The NAS explains its method:

In order to forecast taxes and benefits for an average immigrant and descendants, it is necessary to first forecast the ultimate educational attainment for young immigrants and the future educational attainment of the offspring of immigrants. The panel predicted the education of offspring as a function of parental education using regression analysis based on CPS samples 15 years apart… Adult child education is regressed on parental education by birth region, with separate equations for native-born children versus foreign-born children. This generates equations that are used to predict a child’s ultimate educational attainment…

Big finding: Children of immigrants have markedly greater educational success than you would expect given their foreign-born parent’s education. While children always tend to resemble their parents, the resemblance is stronger when both child and parent are native-born.

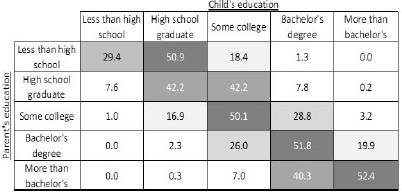

Estimates for children of natives:

Estimates for children of immigrants:

The most striking achievement gaps: Less than 20% of children of native-born high school dropouts go beyond high school, but almost 40% of children of foreign-born high school dropouts pass this milestone. Similarly, about half of children of native-born high school grads surpass their parents’ attainment – versus over two-thirds of children of immigrant high school grads.

What does this teach us about the power of nurture? For the sake of argument, assume that everyone born in the United States enjoys the same educational environment, so genes (and luck) explain all remaining disparities.* Then we can use immigrants’ children’s success to measure the stunting effect of growing up outside the United States! Intuitively: If a native and an immigrant’s children perform equally well, we should infer that their parents had equal genetic potential.

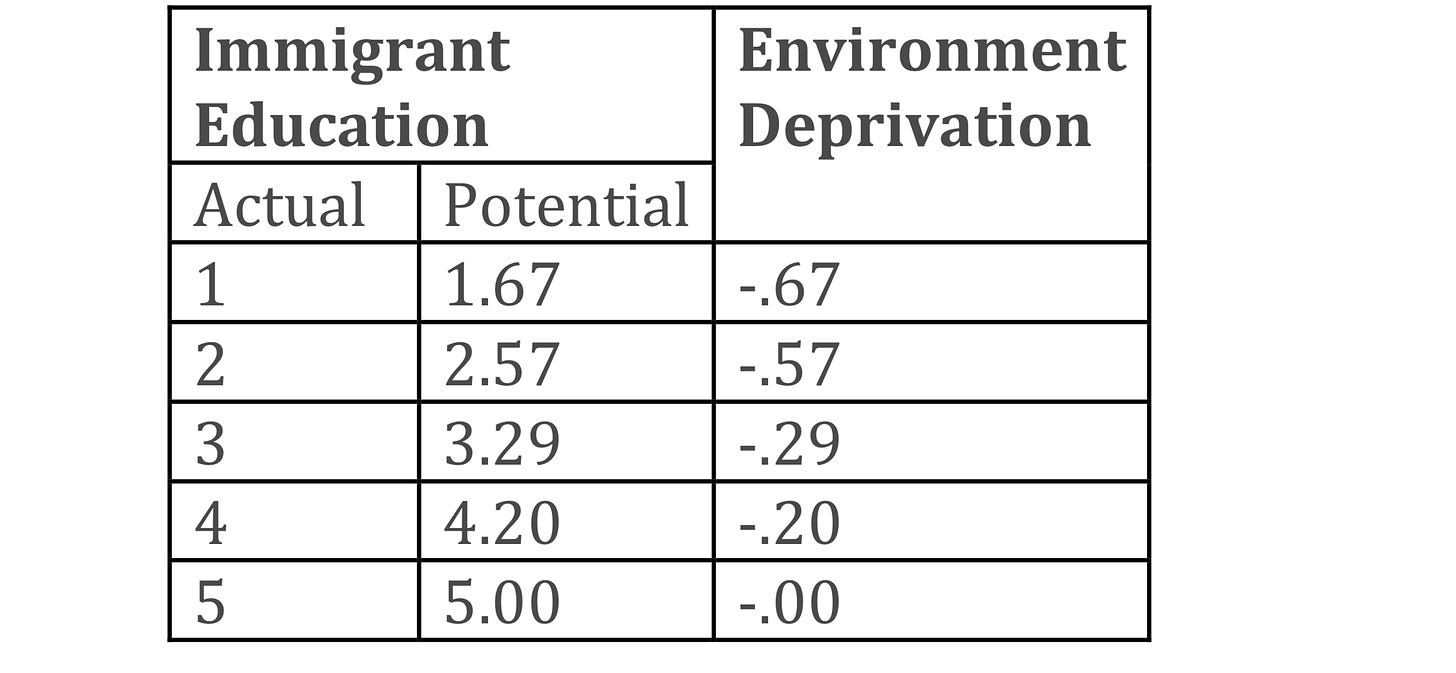

For convenience, let’s code the five educational categories as continuous variables: less than high school =1, high school graduate =2, some college =3, bachelor’s degree =4, more than bachelor’s =5. Then here is children’s average educational attainment E, conditional on their parents’:

Expected Child’s Education (E)

We can use this information to construct another table mapping immigrants’ observed education into their potential education – i.e., the education they would have acquired if they’d been born in the United States. Example: The American-born children of immigrants who didn’t finish high school (E=1) have average attainment E=2.3. That’s two-thirds of the way between kids of natives who didn’t finish high school (E=1.9) and kids of natives who finished high school (E=2.5). In other words, immigrants with E=1 have the kids you’d expect from parents with E=1.67! Filling in the rest of the table:

Now we’re ready to calculate the nurture effects of national origin. There’s no harm at the tip top: Non-Americans with advanced degrees look intrinsically no abler than Americans with advanced degrees. As you move down the educational ladder, however, environmental deprivation goes from moderate (-.20 steps for college grads) to serious (-.57 steps for high school grads, -.67 for less than high school). And if you think that American-born children of immigrant parents are also somewhat deprived, their parents’ estimated environmental deprivation is even worse.

Main doubt: The NAS correlates success for individual parents and their kids. In principle, then, kids of immigrants could have one native-born parent – and kids of native-born parents could have one immigrant parent. Ideally, we’d compare kids of two immigrant parents to kids of two native parents. Given the strong correlation in spousal education, though, this probably understates immigrants’ deprivation. Genetically speaking, an immigrant who marries an equally-educated native is “marrying down.”

The implications for immigration are debatable. So are the implications for education. But the implications for nurture effects are clear. If you grew up in a relatively deprived American home, adoption and twin research imply that your educational success would have barely changed. If you grew up in an absolutely deprived non-American home, however, your educational success would have been markedly worse – masking your underlying genetic potential. The broader but still provisional lesson: Nurture matters after all. Behavioral geneticists have struggled to detect nurture effects because of range restriction – not because there’s nothing to detect.

* Whether or not you buy this assumption, it still sets a lower bound on nurture effects. Keep reading.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

Using education data as a proxy is interesting coming from the guy who wrote a book against education...

It doesn’t make the analysis wrong, just... interesting.

Before the campaign to lower cholesterol started, the children of immigrants, particularly from east Asia, tended to be noticeably taller than their parents. I doubt that stunting ended at the neck.