As promised, here is my reply to Tanmay Khale’s recent guest post. He’s in blockquotes, I’m not.

Dear Prof. Caplan,

I have a quick question regarding your arguments in favor of open borders, and particularly the influence of adverse selection.

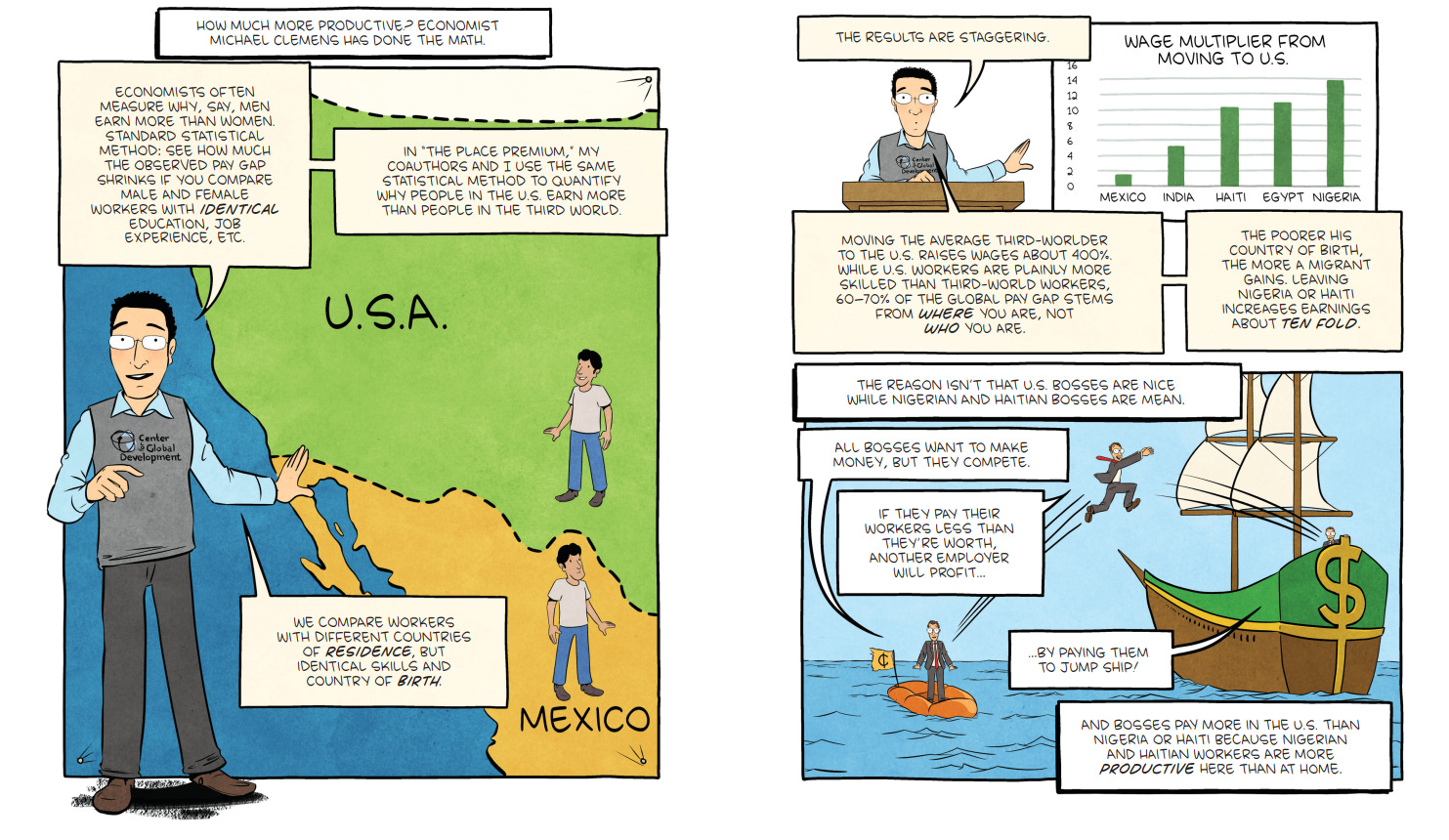

It seems to me that the main thrust of your argument is "the typical person who comes from a developing country to the US sees their wages multiply by 20 overnight, therefore we should let anyone who wants to enter the country (since they are better off with higher wages and society is better off since the 20x wage multiplier comes from increased productivity).” (To be clear, I know that you have a lot more to say than just this; this is just my one-sentence summary!)

To be pedantic, I’ve normally said 5-15x, not 20x, but that’s inessential here.

But the argument above seems structurally similar to "the typical person who starts working at Jane Street sees their wages multiply by 5 overnight, so Jane Street should accept anyone who wants to work at Jane Street,” which seems wrong.

I don’t possess data on compensation at Jane Street, but the idea that their employees are making 5x what they were making before is highly unlikely (unless they were previously students). I’d be amazed if their janitors got 5x what they were earning elsewhere.

Both of these arguments seem like “we have made money from lifting offers in market X; therefore, we should lift every offer in market X.” But this seems like begging to be adversely selected against.

It's true that if you lift every offer, you will get more instances of “positive selection”. You will trade with more people for whom the trade is a mutually beneficial transaction for you and your counterparty. But you will also get more instances of adverse selection!

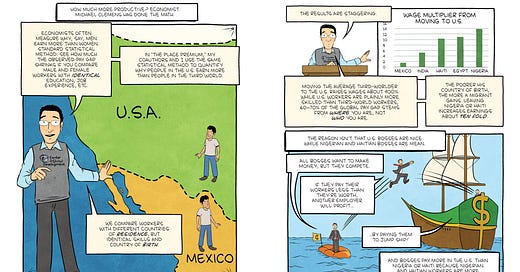

Let’s back up. Estimates of the wage and productivity gain from immigration almost always begin by controlling for observable differences between workers, starting with education, age, and gender. Clemens, Montenegro, and Pritchett’s “The Place Premium,” (CMP) focuses specifically on low-skilled, prime-age males. So the only adverse selection issue that remains is adverse selection on so-called “unobservables” — or to be more precise, on traits unseen by researchers.

The key question, then, is: How well does the current U.S. immigration system screen out immigrants who are subpar in ways that researchers do not observe?

For legal immigrants, the answer is probably: “ever so slightly.” Remember: As of 2018, the U.S. immigration breakdown was 44% immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, 20% family-sponsored, 19% refugees/asylees/crime victims, 13% employment-based, and 4% diversity lottery. U.S. immigration authorities know a little more than researchers about migrants’ criminal records, but for low-skilled migrants, that is based on crummy Third World record-keeping. People with close U.S. relatives are probably a little less likely to end up on the street. But the system is scarcely designed to select people who are better than their demographics would suggest.

For illegal immigrants, the answer is probably: “worse than chance.” While most illegal immigrants just want to make a better life for themselves, the data show they are several times more criminally-inclined than legal immigrants. Part of the reason is that criminals expect to be rejected if they apply to come legally; the rest is that people who are willing to break one law (even a deeply unjust law) are more likely to break other laws (even totally just laws).

Crucially, existing labor data sets normally include both legal and illegal immigrants. So it’s far from clear that U.S. selection on unobservables is currently positive on balance. And if you read “The Place Premium,” you’ll discover that CMP considered the issue of selection on unobservables in depth. Summary: Out of eleven studies, six show positive selection, three show no selection, and two (both of Mexico —> U.S. immigration) actually show negative selection.

In any case, since the measured gains of immigration are massive, adverse selection would have to be massively negative to reverse the basic result.

The reason I bring this up is that in general, it seems like adverse selection makes backtesting challenging, and that's another general reason to be wary of an argument like "people in the past who have come into the US have seen their wages multiply by 20, therefore if we accepted vastly more people, then something like this would continue to hold in the future.”

Sure, be wary — but also don’t make a mountain out of a molehill. U.S. immigration regulation is not Jane Street. It’s not carefully selecting the best of the best. Not even close.

Finally, I know that you mentioned in a podcast that you visited Poland after a huge number of Ukrainian refugees entered the country (something like 10% of the population of Poland in a few months?), and said "Poland is doing fine / great!" This would seem to be a point in favor of the argument that we can admit vastly more immigrants without fear of adverse selection.

But the Poland example reminds me of the following: Being single at age 40 is in general a negative signal about a person’s desirability as a partner, but that isn't true if you know that their spouse recently died of random causes. In the case of Ukrainian refugees, you have a pretty convincing story for why they are coming (that doesn’t have to do with negative signals about the individuals), and so this seems like exactly the kind of situation where you don't have to worry too much about adverse selection! (The Holocaust is another similar example.)…

Since Ukraine tightly restricts emigration of prime-age males, Ukrainian refugees are strongly negatively selected on observables, at least for economic productivity. And since refugees with little to lose are probably more likely to come, they’re probably negatively selected on unobservables, too. If you already have a nice home and a flourishing business in Ukraine, it’s more tempting to ride out the storm, no?

But if your position is rephrased to “we should accept as many immigrants as we can while making sure to vet that they will not be a net cost to our society,” then I just don’t think that this sounds very controversial? I do think (from opinion polls) that most Americans would endorse a statement like the above (Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of skilled immigration, for example).

I wish you were right! But American “support for skilled immigration” hardly implies support for vastly more skilled immigration. In any case, you’re conflating selection on observables with selection on unobservables. Your adverse selection argument is chiefly relevant for the latter case.

When I say “net cost” above, I want to emphasize that when considering restricting freedoms (such as immigration), the only ways that someone could be a net cost to our society which I think are worth taking seriously are the ways in which they could deteriorate the commons, through crime or milder things (e.g. deterioration of liberal norms like democracy and free speech, if it turns out that it’s more pleasant to be homeless in the US than elsewhere, not-quite-crimes like public disorder / harassment, etc.). Again, I know that you give various arguments for why these costs are relatively minimal among immigrants who currently enter the US, but it is far from obvious to me that this would continue to be true if we accepted vastly more immigrants by lowering the threshold for vetting (because of adverse selection), and especially if we accepted anyone who wanted to come.

Again, you’re assuming the U.S. currently has at least a moderately high vetting threshold. In reality, the system combines draconian restrictions with nearly random exceptions.

I am anticipating the objection that open borders are less like lifting every offer on the immigration market, and more like letting people transact freely across borders. Maybe you think “we aren’t paying to bring anyone who wants to come, we just aren’t preventing them from coming.” My immediate response is that the risks above are a form of cost / payment (paid by the US as a whole). Furthermore, when there is a common interest that people’s individual actions don’t necessarily maximize, I think that there is a role for the government is to make good “trades” to maximize this common interest (and not make the bad trades).

All reasonable, until you look at actual government immigration policy! Giving government this role despite its abysmal track record is folly. Indeed, First World governments are so dysfunctional that they deliberately amplify adverse selection by refusing to build walls around their welfare states.

I think deciding to let someone live in and transact with the US is such a trade, in the same way that deciding whether or not to let someone be a customer at your exchange based on your assessment of their credit risk is a trade; even if most customers make you money and improve the value of the exchange, adverse selection should make you a little paranoid to lift every available offer, especially since the cost (if the exchange goes under) is paid by all of the customers.

I say you should focus on risks that we know from experience to be large, and not be distracted by trivial risks. And we should heavily distrust organizations, like the U.S. government, that habitually do the opposite.

P.S. Khale sent me a follow-up. I reproduce it below, along with my further responses.

Thank you again for featuring my guest post! There are two quick things I wanted to add, but was worried about making the post too long. You can feel free to quote these in your response if you want, or just ignore this:

First: Adding a sentence to my previous email (in bold):

It's true that if you lift every offer, you will get more instances of “positive selection”. You will trade with more people for whom the trade is a mutually beneficial transaction for you and your counterparty. But you will also get more instances of adverse selection! And when you reduce the degree to which you vet offers, you should expect the (marginal) proportion of instances of adverse selection to increase, since vetting is the one lever you have available to pull to decrease adverse selection.

Unless, of course, your vetting is ineffective or perverse. Which it probably is in the U.S. and throughout the First World.

Put another way: I think an essential lesson of adverse selection is "the person who is putting an offer on the book (the market maker) is at a disadvantage because the people looking at the book (the market takers) can see the offer and decide (with the information that the offer is on the book) whether to take it or not.” This is why you should always expect market makers to show spreads; it’s also the advantage of being “in position” in poker. But if you’re the taker, you give up this “taker’s advantage” if your strategy for taking is "lift every offer on the book" (much like how you don’t have an advantage “in position” if your strategy is to call everything). If that is your strategy (and if it is well-known that that is your strategy), then you're the one who is extremely vulnerable to adverse selection, because your strategy is equivalent to putting a permanent bid of +infinity on the book!

Hyperbole. Just think of all the businesses that offer unlimited money-back guarantees. Does this create an adverse selection problem? Sure: The people most likely to be swayed by a guarantee are also the most likely to exercise it. Is this a bad business strategy all things considered? Probably not. Do you really want to second-guess CostCo?!

Second: The most obvious (and most often cited?) example of adverse selection in immigration is the claim that with open borders, people will come to the US to take advantage of its generous welfare system. The reason I didn’t mention this in my email is because I think your response of “if that’s your problem with immigration, why not adopt the keyhole solution of building a wall around the welfare state” is basically a knockdown rebuttal of this concern. However, it doesn’t seem to me that there’s a simple “keyhole” solution to the other adverse-selection related concerns (I think vetting is the natural solution to those).

Au contraire. Here are two simple keyhole solutions to government vetting.

Admit anyone with a sponsor who agrees to be financially responsible for their alleged downsides.

Admit anyone who posts a bond. Refund the bond after a trial period if no problems arise. Or gradually refund it continuously if you prefer.

But to be clear, these are keyhole solutions in search of a problem. The research already shows massive gains for low-skilled workers conditioning on observables. And the idea that unobservables of unadmitted immigrants are sharply worse than those for admitted immigrants' is fanciful.

The canary in the coal mine is Canada, UK, and Australia. Three large Anglo countries across three different continents.

All went "all-in" on infinite Indian immigration the last decade. All stagnating on a per capita GDP basis. All failed to create Silicon Valley 2.0. All consider it a failure and incumbents are losing big time.

Silicon Valley is an ethos. Risk taking, non-conformity, and a variety of anglo values.

Hot house cram school culture is the opposite.

And Indian culture in particular, with its nepotism, corruption, dishonesty, and factionalism is particularly toxic.

Indian values are great for ruthlessly taking over existing institutions, but not building or maintaining them. The rest of the anglo sphere already figure this out.

Ironically, it would be in the best interest of existing Indian immigrants to cut immigration. They already have a critical mass of co-ethnics. Further immigration will "dilute the brand" and cause massive strain with the native populations as happened in the other anglo countries.

Like Catholic Europe in 1924 or Hispanics in the 2024 election, Indians need to recognize that a break is necessary to facilitate proper assimilation.

Is there enough asymmetric information to create adverse selection? Criminals and welfare bums might have some asymmetric information, but these were excluded from the argument. What remains seems to be the potential for some mysterious damage to the commons. Is the idea that people come here with the explicit purpose of changing the culture negatively? Are they any more likely to succeed than those who are here already trying to do the same thing?

Any change is seen as negative by someone. Is it really the case that non-criminal immigrants have such divergent preferences that we should count them as a negative externality?

The reliance on a weak analogy with financial instruments makes Khale's argument confusing and unpersuasive. It is fair to worry about criminals and welfare bums and the difficulty of distinguishing them from others, but it seems unfair to punish others because of this difficulty. Perhaps it is necessary none the less, but Khale's argument does not make this more apparent to me.