Update: Alex Tabarrok, who partly inspired the original post, reflects on the puzzle.

A large majority of American college students — almost three-quarters — go to public schools. For four-year colleges, it’s about two-thirds. Yet strangely, these “public” schools aren’t equally open to the entire public. Almost all public four-year colleges are run by a state government — and every one of the fifty United States has at least one such college. While these schools accept students from all over the world, they almost always charge students from their own state much lower tuition. In the most recent data, average out-of-state tuition for four-year colleges was $26,382, versus $9,212 for in-state — roughly a 3:1 ratio.

This is a tough break if you’re from Wyoming, which has only one state school, the University of Wyoming. You can either pay $6,612 and go there, or leave the state and pay though the nose.

In theory, out-of-state students can eventually acquire residency. In practice, however, residency rules are designed to prevent that from happening, though some interstate reciprocity agreements exist.

Once people understand the system, they usually want to quarrel about its “fairness.” State residency requirements are barely allowed for welfare programs; why should college attendance be any different? Defenders of the status quo naturally respond that since the state’s residents fund state schools, it’s only fair for their children to get a better deal.

But I want to ask a totally different question: What do we learn from the tuition disparity? How could this massive price gap emerge and endure?

It’s tempting to just blame “monopoly power.” But there are many competing public universities at virtually all levels of selectivity. (Exception: There are zero public schools in the top ten). Not only would collusion be hard to orchestrate, but treatment of non-resident students varies considerably from state to state. If out-of-state students were really being charged prices far above cost, you’d expect each state to try to “steal” as many as possible from competing states.

The straightforward explanation for the persistence of the massive price gap is that only in-state students are massively subsidized by their state governments. So instead of picturing out-of-state tuition as a “monopoly price,” we should think of out-of-state tuition as the roughly competitive price.

Which has a shocking implication: Despite much fretting about the exorbitant cost of college, state (and to some extent local) government picks up about two-thirds of the tab.

Many observers will balk at this inference. Official per-student state appropriations are normally far less than two times tuition. In the latest UVA budget, for example, tuition is about $900M, versus a Virginia subsidy of around $250M. But this overlooks a long list of subtler state subsidies, past and present. The initial grant of land. The start-up capital. The implicit endorsement of the state government. Favorable regulatory treatment. And don’t forget the value of goodwill. The state government anoints your institution of higher learning, largely in-state students attend, then grow up to be loyal and generous alumni.

If you remember your basic micro, you could further object: “These subsidies are all lump sum, anyway. Only per-unit subsidies should cut tuition.” But the strategic situation is more complicated. The sum of all state subsidies, past and present, implicit and explicit, allows public colleges to operate at a large loss. The quid pro quo, however, is that state governments heavily pressure their subsidized colleges to favor residents. Indeed, this pressure for favoritism is so intense that elite state schools often cap out-of-state admissions. UVA, for example, publicly pledges to limit non-residents to one-third of its student body, even though it could easily get far more at full price.

Another objection is that I’m focusing on the list price of higher ed instead instead of its net price. True, but if we use the latter, better measure, the puzzle probably gets even bigger. Most schools prefer to give discounts to in-state students. And even if they didn’t, they’d have to give triple the absolute discount just to keep the price ratios constant.

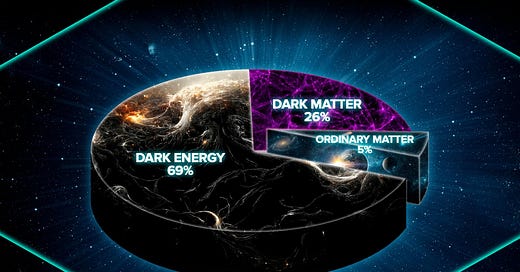

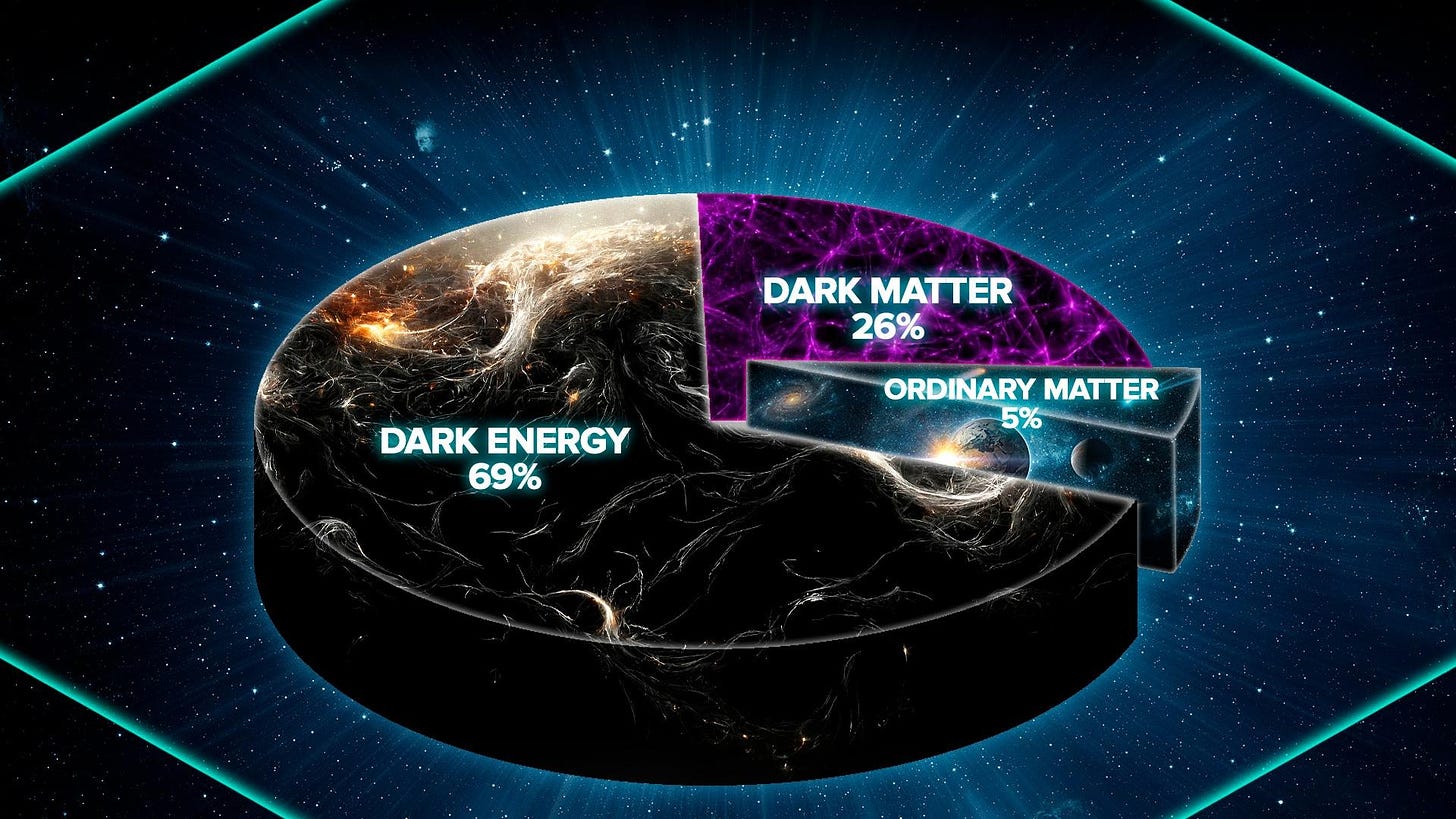

I grant that I’m making a “dark matter” argument: If I’m right, poorly-measured subsidies to higher ed vastly exceed measured subsidies. Implausible? You have to weigh that against the competing implausible story that hundreds of state schools have somehow managed to maintain ruthless cartel pricing for many decades.

Confession: I’ve long believed that non-profits often lethargically fail to capture profit opportunities. Tenure is dysfunctional, and colleges could easily fire half their admins. But I still struggle to believe that individual colleges would leave this much easy money on the table. Due to product differentiation, perhaps schools could durably hold out-of-state tuition at 20% above cost. Maybe even 50%. But 200%?!

Whatever your position, you’ve got to admit that persistently high out-of-state tuition is a major puzzle in a major industry. My resolution is that state governments have and continue to provide vastly more support than they publicize in their budgets. The upshot is that higher ed is a lot more socialist than it looks. Not quite as much as K-12, but much closer to K-12 than a free market.

Deem me crazy? Fine, but don’t stop there. Rise to my challenge by crafting a better explanation of the out-of-state tuition puzzle.

The comments, as usual, are open.

Politicians buy votes by bribing constituents with cheap goods (degrees), laundered through the state university. Out of state students are not the children of their constituents. How is this complicated?

I don't think Brian is entirely wrong, but I do believe there's an element of price discrimination/market segmentation here. Airlines charge more for flights close-in because people value travel for business, funerals, family emergencies and such more than elective leisure travel. Out-of-state students probably value their specific choice of school significantly more than in-state students. After all, they are willing to go out of state or even country to get it. They really want a specific name (or narrow band of names) on that degree, maybe for status or maybe because dad and granddad went there or maybe they just love the sports team. In-state students are more likely to go because college is the next step and X State U is the first place that comes to mind when you live in state X.