When I was touring Mexico last year, my family stayed at a virtually vacant hotel on a vast estate. The hospitable staff, with little to do thanks to Covid, gave us a grand tour of the grounds. Along the way, they pointed out a bunch of minor Mayan artifacts. And in hushed tones, they asked us not to alert the authorities. If the government of Mexico knew they had artifacts, they might be legally seized. Or worse.

Nor is Mexico especially harsh. Around the world, governments claim ownership of archeological finds on private property. And the result is predictable: Archaeology lives in chains. People have little incentive – or even a negative incentive – to hunt for artifacts. As a result, the glorious patrimony of humanity stays in the ground.

Admittedly, there is a black market, but it’s tiny compared to what could have been. After all, one of the main reasons to buy artifacts is to publicly display them – and it’s dangerous to publicly display evidence of criminal complicity.

Wouldn’t legalizing the market lead to trespassing and theft? Almost surely. If you let people make money selling corn, this encourages people to sneak onto cornfields and steal corn. Yet at the same time, it encourages people to protect their cornfields. Compared to the gains of private property rights, the costs of trespassing and theft is a rounding error.

The main problem with my proposal is that the government has already seized a lot of the most archaeologically promising land. So just respecting private property rights isn’t enough. Instead, governments need to privatize this land forthwith. Have some big auctions and pay down their national debt.

Wouldn’t foreigners swoop in and win the auctions? To a large extent, yes. And that’s good. It’s called foreign investment, and it’s the best-known way to spread prosperity from the First World to the Third. Because foreign investment is not just know-how, and it’s not just technology. It’s leadership.

Wouldn’t this be a return to the bad old days of colonialism? Well, colonial powers did many bad things, but allowing a largely free market in antiquities was not one of them. The 19th-century was a golden age of archaeology. If modern laws had been enforced back then, much – perhaps most – of the best stuff in modern museums would remain undiscovered. The idea that artifacts rightfully belong to “the nation as a whole” is classic flowery socialist rhetoric, with classic dismal socialist results.

In any case, even if you cling to the ideal of collective property, there is a keyhole solution: Instead of banning the sale of artifacts, just tax it. This allows “the nation as a whole” (i.e. the government) to capture much of the surplus, without crippling the industry.

Is any country rich in archeological treasure likely to take this free-market route? As usual, no. Though perhaps my friends in Guatemala could manage to make something good happen. Right now, Guatemala is full of barely-excavated Mayan sites; they don’t have the funds to do much more than maintain what they’ve already got. Legalizing the market – and auctioning off government-owned sites to the highest bidder – really could transform the Guatemalan economy – and bring riches to many of their poorest communities.

Yes, let Disney buy Tikal. Only nationalist and socialist demagoguery stands in the way.

P.S. While we’re at it, we still need to privatize Lenin.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

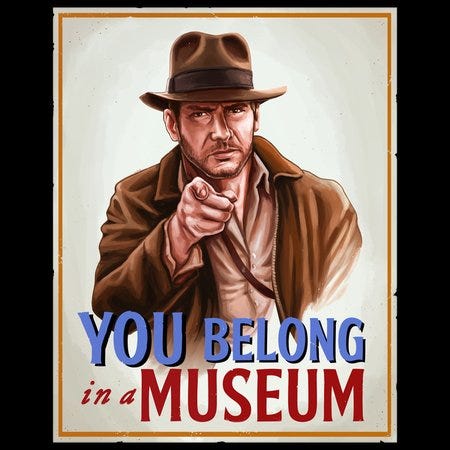

It belongs in a Museum!

I had similar thoughts traveling about Turkey last year. In some places, anywhere you turn, there's some as yet unexcavated Roman ruin. I think its government is more competent and certainly less criminalized than Mexico's, but under state management, it will be decades and a trebling of GDP before many of these sites get excavated.

If there was to be a free market in archaeology, I could see archaeology DAOs being created amongst enthusiasts to finance prospective digs. NFTs can be minted for every artifact discovered and token holders above a certain level rewarded with them.