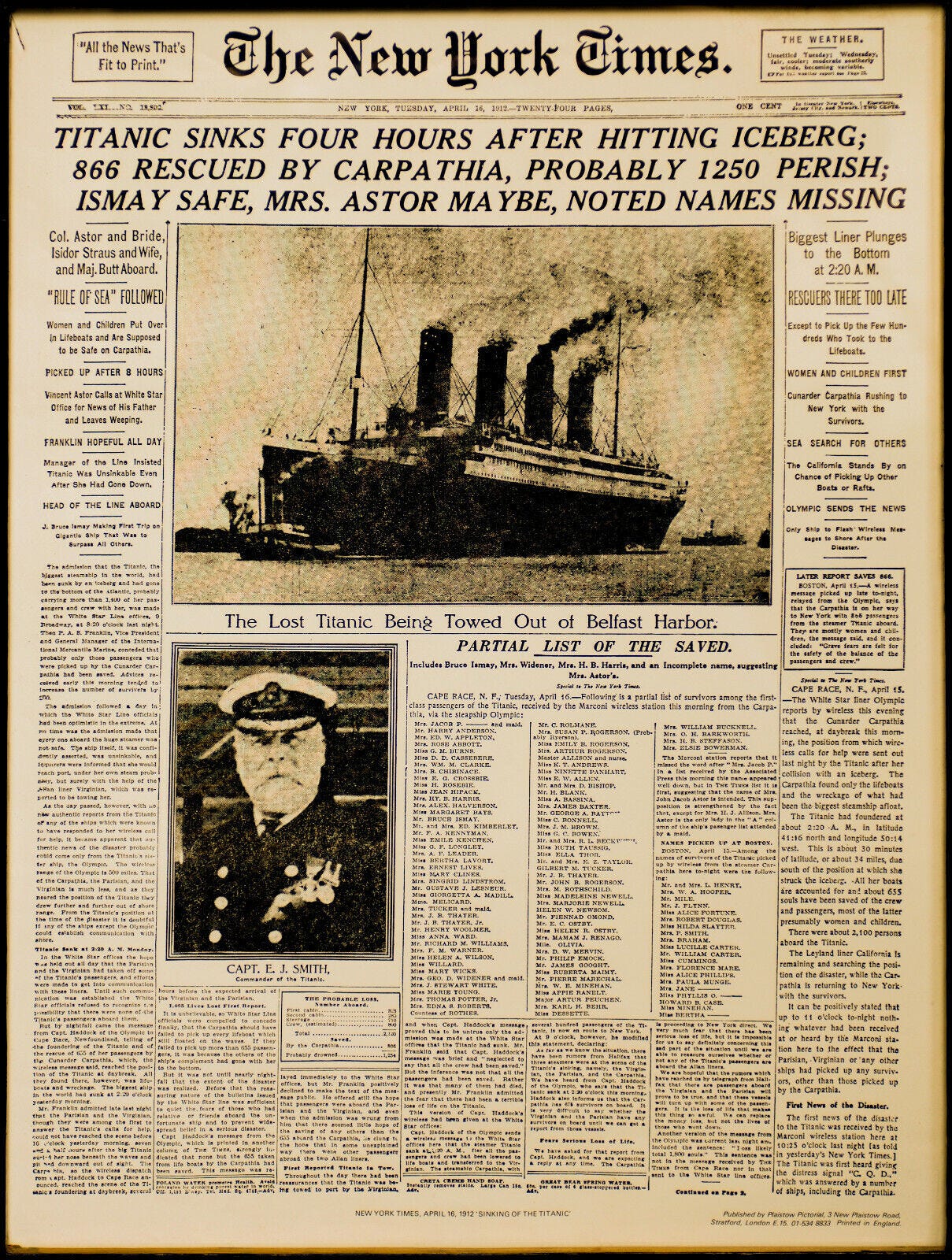

Titanic recently returned to the big screen, and I was delighted to revisit this cinematic classic at my local theater. Besides being a feat of story-telling and movie magic, James Cameron’s Titanic is also a rich work of intended and unintended social science and moral philosophy. My top thoughts:

Titanic is a strangely triumphalist work; its Big Picture message is that Anglo-American society in 1997 is vastly morally superior to Anglo-American society in 1912. Why? Titanic shows a thankfully defunct world where rich male jerks unapologetically dominate society, the economy, and the family. While you could say, “What’s changed?,” that’s not Cameron’s take. Instead, he aims to show us “how far we’ve come.” In 1912, we had a grotesque class society; in 1997, it’s both more egalitarian and more meritocratic. In 1912, men held women like property; in 1997, women enjoy roughly equal treatment. Cameron also depicts a 1912 where rich businesspeople, not politicians, are the ultimate rulers. The politics of 1997 don’t explicitly come up, but Titanic heavy-handedly hints that in the modern world, the people rule instead of the plutocrats.

Titanic is also a deeply feminist film, though some feminists still find fault with it. Ruth, mother of the young heroine Rose, self-righteously pressures her daughter to marry a rich jerk she does not love. Why? Because her dead husband lost the family fortune. Which inspires these classic lines:

Rose:

It's so unfair.Ruth:

Of course it's unfair. We're women. Our choices are never easy.Notice: It isn’t just free-thinking Rose who feels oppressed by men. Rose’s conservative mother also takes it for granted that society treats women less fairly than men. The difference is that Rose openly challenges male rule, while Ruth only tries to game the rigged system.

How are we supposed know with great confidence that 1912 is morally inferior to 1997? Above all else: Because back in 1912, poor people travelled in steerage. Not only are their accommodations terrible; deck space is segregated by class. The poor can’t even attend church with the rich; God, apparently, does not want the lower orders to burden their betters with their unseemly presence. The steerage passengers even endure the indignity of a lice inspection. As Tommy the Irishman puts it:

Tommy Ryan:

That's typical. First class dogs come down here to take a shite.Jack:

That's so we know where we rank in the scheme of things.Tommy Ryan:

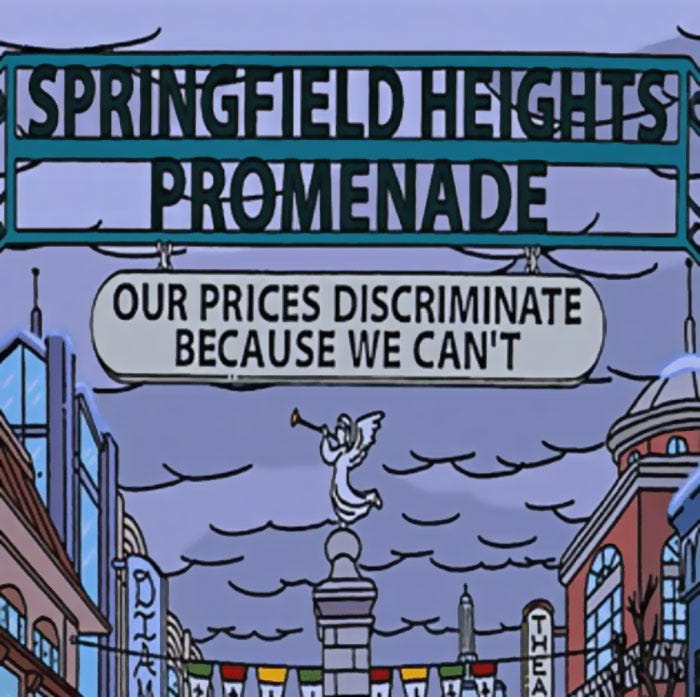

Like we could forget.Part of what makes Titanic fun is that the movie’s official Big Picture deeply conflicts with the social world it actually shows. Cameron evades a harsh reality: Modern cruise ships got rid of steerage by getting rid of poor passengers altogether! Superficially, passengers today enjoy much more equal treatment. Every paying customer is free to mingle with every other paying customer. Substantively, however, we’re less equal than ever, because the only folks on the ship familiar with absolute poverty are the crew. To quote a classic Simpsons line: “Our prices discriminate because we can’t.”

Many of the steerage passengers, including Fabrizio the Italian and Tommy the Irishman, are immigrants. Since the year is 1912 - at the tail end of the open borders era - all they need to legally migrate to the U.S. is the price of a steerage-class ticket. Just £7 nominal! Fabrizio doesn’t even show a passport to board the ship - though Jack does falsely claim his Italian friend is American to avoid the lice check. So despite the heavy-handed “rich versus poor” narrative, the policies of 1912 aren’t merely better for the global poor than 1997’s. They are vastly better.

The real transformation between 1912 and 1997, then, is not modernity’s egalitarianism, but its nationalism. Today we’re so nationalistic that we implicitly define equality as “equality within our national family.” In 1912, in contrast, capitalist internationalism still prevailed. Ideologically, alas, it was on its last legs, but from a rational point of view, capitalist internationalism was better than what succeeded it.

There is a similar chasm between Titanic's feminist message and the facts of the story. Though both Ruth and Rose feel horribly treated, the truth is that their consumption is very high while their production is zero. These female aristocrats are on an historic ship designed by men, built by men, run by men, and managed by men, but Rose still paints herself as a “slave.” You could reply, “In a world where women had equal opportunities, Ruth and Rose could have been millionaires on their merits, too.” Possibly, but what are the odds? Ruth frets that if Rose calls off her marriage, she’ll end up as a seamstress. Which seems like a reasonable prediction, because in 1912 there were far more seamstresses than millionaires. Ruth and Rose never compare their quality of life to that of the median male, much less a coal-shoveler in the engine room. They compare their quality of life to that of the most elite males.

The absurdity of Titanic’s feminist philosophy becomes truly gruesome once the ship starts to sink. Why? Because the adage of “women and children first” suddenly determines who lives and who dies. Yes, elderly spinsters who have never worked a day in their lives officially count more than the most promising young adult males. Cameron treats this norm as sacrosanct, without explanation. When Cal tries to shoot Jack, he’s bad; but when Cal pretends to be a father to get on a lifeboat, he’s the scum of the Earth.

What would the morally correct life-saving algorithm for Titanic have been? At risk of horrifying all, the ideal algorithm would have been contractual. When you buy your ticket, you also buy your lifeboat boarding group if the ship happens to sink. Doesn’t this mean that you save the rich first and the poor last? Almost certainty. But it also means that the poor get cheaper tickets, which makes passage to the New World even more affordable for the people who need it most. Ex ante - though perhaps not ex post - it’s win-win.

What if there’s no contract - not even implicit? In that case, I’d go full utilitarian. Give high weights to (a) social productivity, (b) remaining years of healthy life, and (c) how much other people will miss you. Factor (a) leads you to save all the captains of industry and other high-skilled workers… unless they’re very old. Factors (b) and (c) lead you to save the kids. Factor (c) leads you to save parents of young kids. Granted, factor (c) argues for prioritizing moms over dads; even today, most people are much closer to the former than the latter. Factor (a), however, argues for prioritizing dads over moms; even today, the former contribute a lot more to the economy than the latter.

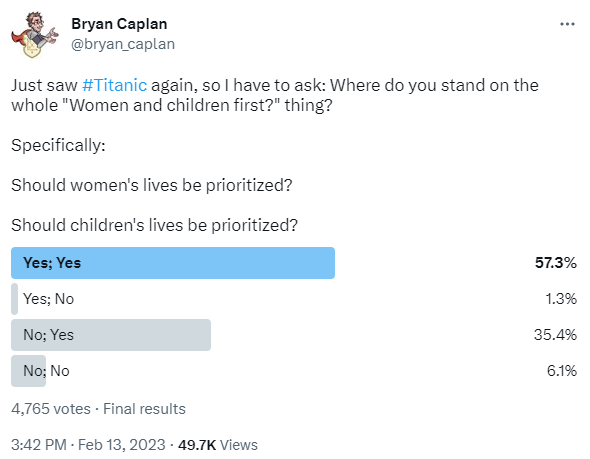

If the “women and children first” norm seems obsolete, it still commands wide adherence. Despite self-selection, it still won a supermajority in a Twitter poll I ran:

This nicely illustrates my claim that feminism succeeds in large part by building on a pre-existing belief that female well-being - and especially female suffering - counts more then men’s. As I explain in my essay, “Don’t Be a Feminist: A Letter to My Daughter”:

Even when the males are literally dying, it remains rhetorically easier to get people to lament the collateral misery of the women who knew the fallen. Feminism succeeds because it is false; claims about the unfair treatment of women capture our attention because men and women in our society especially abhor the unfair treatment of women.

See the original essay for relevant cites.

When I first watched Titanic, I was scarcely older than the lead characters. As a non-conformist, I naturally sympathized with them against the rest of society. A quarter century later, I have kids the age of Jack and Rose. Yet I continue to take the side of youth over maturity. Cal was a beast, and a beast with money remains a beast. Rose was right to choose Jack because he had character. True, I can see why Ruth would fear that Jack and Rose’s romance wouldn’t last, and I wouldn’t care to become a seamstress late in life either. At minimum, though, Ruth should have helped Rose shop around for a well-off husband with character, instead of going all-in on vicarious one-itis for Caladon Hockley.

Titanic is still in theaters; see it on the big screen while you can.

> Modern cruise ships got rid of steerage by getting rid of poor passengers altogether!

Aren't ships the wrong reference category, since they are no longer much used for practical transportation of passengers? Probably travel by air, a more common option now, would be more appropriate choice. The price you give for a Titanic ticket is 7 British pounds in 1912; according to https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator that's equivalent to 632.8 pounds today; at the current exchange rate of 1.217 US dollars per British pound, that's equivalent to about $770 in modern US dollars. Meanwhile, http://archive.today/2023.03.14-171806/https://www.travelocity.com/Flights-Search?filters=%5B%7B%22numOfStopFilterValue%22:%7B%22stopInfo%22:%7B%22stopFilterOperation%22:%22EQUAL%22,%22numberOfStops%22:0%7D%7D%7D,%7B%22numOfStopFilterValue%22:%7B%22stopInfo%22:%7B%22stopFilterOperation%22:%22EQUAL%22,%22numberOfStops%22:1%7D%7D%7D,%7B%22numOfStopFilterValue%22:%7B%22stopInfo%22:%7B%22numberOfStops%22:2,%22stopFilterOperation%22:%22GREATER_THAN_EQUAL%22%7D%7D%7D%5D&leg1=from:London%20(LHR-Heathrow),to:New%20York,%20NY%20(NYC-All%20Airports),departure:6/1/2023TANYT&mode=search&options=carrier:*,cabinclass:,maxhops:1,nopenalty:N&passengers=adults:1,children:0,infantinlap:N&sortOrder=INCREASING&sortType=PRICE&trip=oneway lists the minimum price of a plane ticket across the Atlantic as just $443.

Curiously, the heroine, now grown old, does something no woman I’ve ever known would ever do.