Some of the major figures of the Enlightenment included Cesare Beccaria, Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, John Locke, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Hugo Grotius, Baruch Spinoza, and Voltaire.

— Wikipedia on “The Age of Enlightenment”

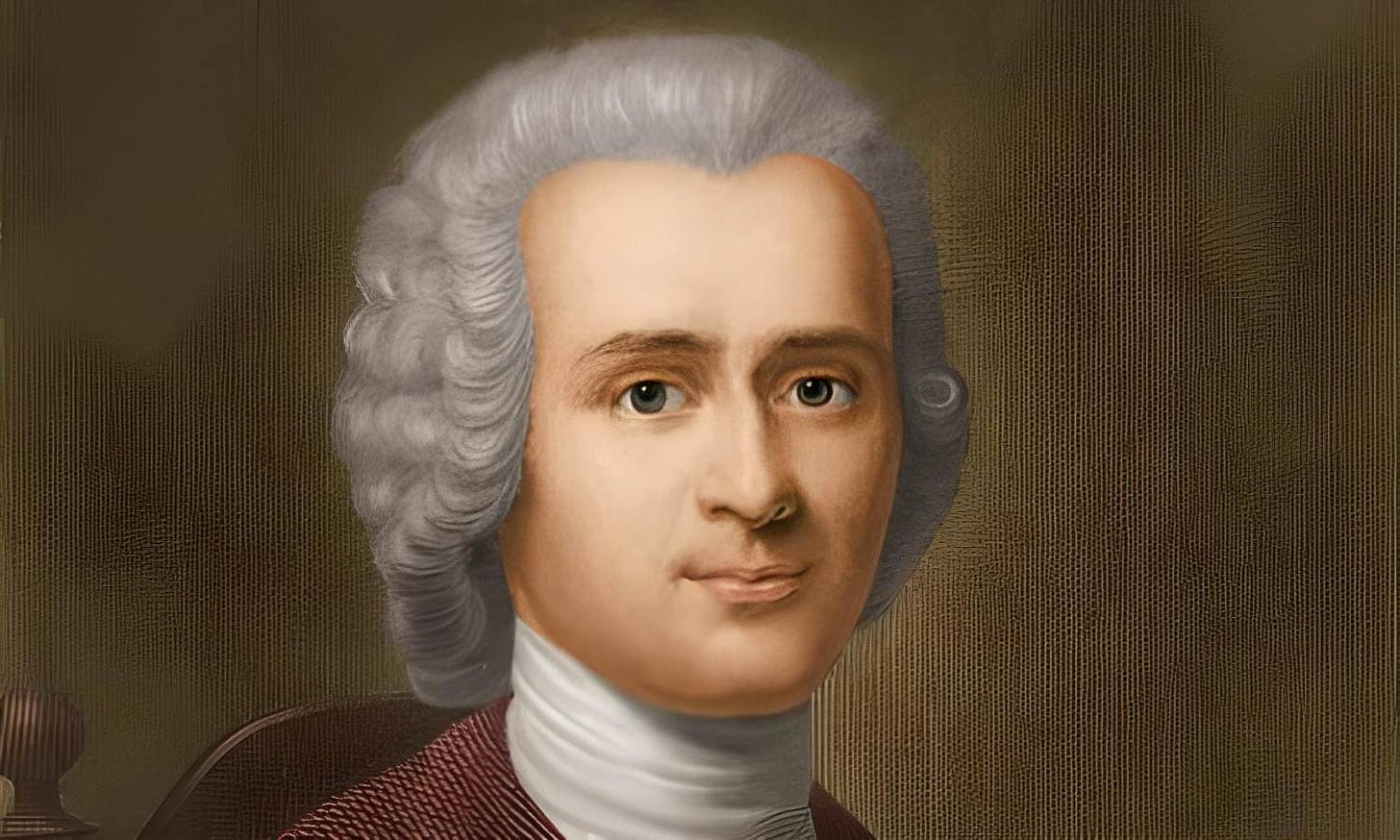

Which of these thinkers is unlike the others? The correct answer is, of course, Rousseau. Everyone else on the list was a genuine fan of rationalism or individual freedom. Usually both. Rousseau, despite his personal ties to key Enlightenment figures, carved out a staunchly contrary position - irrationalist and statist to the core. To call him a generic “national socialist” would be quite fair. If Orwell’s “Freedom Is Slavery” slogan ever struck you as over-the-top, try Rousseau’s notorious line from The Social Contract:

Whoever refuses to obey the general will will be forced to do so by the entire body; this means merely that he will be forced to be free.

Why bring up Rousseau? Because the next installment of “lost lectures” of the late great George Walsh explores his thought in detail, covering the major works of this “citizen of Geneva” chronologically. As usual, Walsh is meticulous, judicious, and hilarious. This master of intellectual history is harsh, but fair.

The first lecture situates Rousseau in the history of ideas, then goes over the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences and the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality:

The second lecture turns to the Discourse on Political Economy, Emile, and The Social Contract:

The big remaining question, to my mind, is how much real-world influence Rousseau actually had. Pace Brian Leiter, Karl Marx was plainly a big proximate cause of history’s many Marxist despotisms and bloodbaths. If ever there was a smoking gun from ideas to atrocities, the gun’s registered owner was Marx. It’s tempting to similarly blame Rousseau for the horrors of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. But while Robespierre was indeed a big fan of The Social Contract, the French revolutionaries (a) clearly had an array of intellectual influences, and (b) were deeply confused. Article 4 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen manages to sound radically libertarian and savagely statist in rapid sequence.

Article 4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

Unfair? Read the whole document and feel the ideological whiplash. It’s Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau in a blender. Article 8: “The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and obviously necessary.” Article 6: “Law is the expression of the general will.” What if the “general will” prescribes a punishment that is not strictly or obviously necessary? Hmm, maybe we need a punishment for asking such questions.

In the end, my best guess is that the French Revolution would have turned totalitarian with or without Rousseau. You don’t need a national socialist philosopher to come up with lazy bloody slogans like, “No one shall be executed, except by law.” Deep hatred plus fanaticism plus power-hunger will suffice.

Rousseau is the Pepé Le Pew of philosophy.

I have denied knowledge therefore, in order to make room for faith.

-Kant

Kant, greatly influenced by Rousseau, created a comprehensive, systematic, technical, philosophical rationalization of his irrationalism. He starts his philosophy inside consciousness split from reality and never leaves it. Eg, he splits perception, experience, reason and ideas from reality. Kant is the major modern philosopher of the unfocused mind. Both Marx and Hitler agreed by explicitly basing their ideas on intuition. Kantian nihilism, the hatred of values (absolute sacrifice, duty) and their basis, reason. Kant deliberately and explicitly ended the Enlightenment to save the religious morality of sacrifice. He claimed that a sense of duty was a revelation from God. He explicitly advocated a life of suffering and made suffering the mark of morality.