The Fault Is Not in Our Stuff But in Ourselves

Bruce Sacerdote‘s NBER Working Paper, “Fifty Years of Growth in American Consumption, Income, and Wages” provides a nice update on the measurement of CPI Bias. The punchline should be obvious, but it’s great to hear such an eminent economist say it: “Meaningful growth in consumption for below median income families has occurred even in a prolonged period of increasing income inequality, increasing consumption inequality and a decreasing share of national income accruing to labor.”

Highlights:

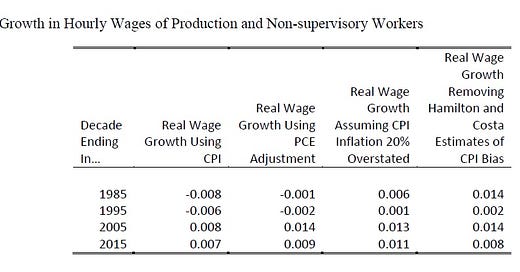

Table 3 shows estimates of annualized growth rates in wages by decade. The first column shows growth in real wages using CPI deflation. This column show real wages fell by 0.8 percent per year during the ten years January 1975-January 1985 and fell by 0.6 percent per year during the ten years ended in 1995.10 In the subsequent two decades wage growth is positive 0.8 percent per year and 0.7 percent per year respectively.

The next three columns calculate growth in real wages using a) PCE adjustment, b) an assumption of 20% upward bias in CPI growth, and c) Hamilton/ Costa adjustment to CPI. The picture looks progressively more optimistic as we move from left to right. PCE adjustment still has negative wage growth in the first two decades (75-85 and 85-95) but the decreases in real wages are smaller. Hamilton/ Costa bias adjustment implies annual real wage growth of 1.4% during 1975-1985, .2 percent per year during 1985-1995, 1.4 percent during 1995-2005 and .8 percent in the most recent decade.

The table in question:

More:

Consumption for below median income families has seen steady progress since 1960. My preferred point estimates are based on CEX measures of consumption where the price index has been de-biased following Hamilton and Costa. These estimates suggest that consumption is up 1.7 percent per year or 164 percent over the whole time period. These estimates of growth strike me as consistent with the significant increases in quality and quantity of goods enjoyed by Americans over the last half century. And my conclusions are consistent with the findings of Broda and Weinstein (2008). Estimates of slow and steady growth seem more plausible than media headlines which suggest that median American households face declining living standards.

The bias adjusted estimates also provide a more positive outlook on real wage growth in the last 40 years than standard media headlines. PCE adjusted wages appear to have grown at .5% per year during 1975-2015 while the de-biased CPI adjusted wages grew at 1% per year over the same time period.

Key caveat:

Importantly these estimates do not tell us anything about why wages grew more slowly than GDP or why inequality increased. CPI bias does not explain decreases in labor’s share of income (Krueger 1999) or the associated rise in inequality (Pikkety and Saez 2003). Adjusting the price index downward leads to higher estimated real wage growth and higher estimated real GDP growth.

The big unanswered question:

What I do not address here is why Americans feel worse off if consumption is actually rising. There are at least four important explanations that may be at work. First, I am only examining consumption within very large sections of the income distribution and there may be specific groups (for example less than high school educated men) for whom consumption is actually falling. Second, it’s possible that the quality of some services such as public education or health care could be falling for some groups. Third, the rise in income inequality coupled with increased information flow about other people’s consumption may be making Americans feel worse off in a relative sense even if their material goods consumption is rising. Fourth, changes in family structure (e.g. the rise of single parent households), increases in the prison population, or increases in substance addiction could make people worse off even in the face of rising material wealth. A deep future research agenda would be to understand how America has lost its sense of optimism about living standards and whether the problem is one of consumption, relative consumption (relative to other people) or something entirely different.

My favorite candidate for “something entirely different”: false consciousness. Most people embrace a dogmatic pessimistic ideology, and believing is seeing. Hedonic adaptation amplifies the problem. After all, it’s easier to deny that your standard of living is great than to admit that you’re unhappy despite your affluence. The fault is not in our stuff but in ourselves.

The post appeared first on Econlib.