As I show in The Case Against Education, the main purpose of education is signaling. Specifically, students’ goal is to convince prospective employers that they are smart, hard-working, and conformist. This only works if schools are somehow elitist. The school that equally certifies everyone certifies no one.

Admins at elite schools have long felt guilty about this truism. Since they work at non-profits with massive endowments, though, they have long been able to assuage their guilt by supplementing their institutions’ main purpose — signaling — with philanthropy. Things started out innocently enough with merit scholarships: You fund outstanding students from poor families to help them shine. Alas, the guilt remained, because outstanding students from poor families are few and far between. As a result, top schools started sacrificing their primary elitist mission of signaling in favor of their secondary egalitarian mission of charity. The more you lower your standards, the more you help the truly disadvantaged — and the more you dilute the value of your degree.

Traditionally, the U.S. News and World Report rankings were one of the main checks on such behavior. If Harvard admitted students solely based on need, their official ranking would plummet. This, in turn, would make the “gift” of a Harvard degree all but worthless. One incompetent graduate won’t destroy your signal, but a generation of incompetent graduates will.

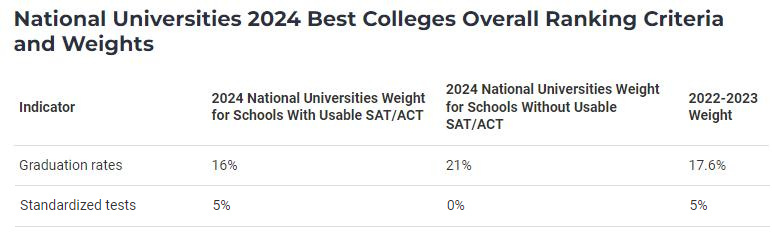

Recently, however, U.S. News and World Report revised their ranking formula. How do the revisions alter the trade-offs of elite schools? The most obvious novelty is that there is now one formula for schools with “usable SAT/ACT data” and another formula for schools without such data. So if your students’ test scores are low, just don’t use them, so your ranking depends on graduation rates instead! (Last step: Lower standards until your graduation rates hits 100%).

The revised formula also assigns zero weight to high school class standing. This is already a corrupt measure, because being #1 at Stuyvesant is rather different than being #1 at Ballou. Still, a corrupt measure of merit is better than no measure of merit at all.

If you scrutinize the U.S. News and World Report formula, you’ll see that meritocracy was already on the decline in 2022-23. The formula already put 8% weight on “Graduation Rate Performance,” which bumps schools up if their graduation rates exceed what you’d expect given their students’ test scores, class ranking, and other factors! Yes, that literally means that you get a better ranking if you admit unqualified students, then graduate them anyway.

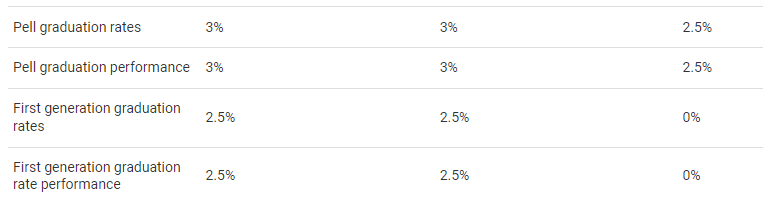

The revised formula boosts the weight on this perverse measure from 8% to 10%. And the other boosts are similarly perverse. It puts slightly more weight on Pell graduation rates and Pell “graduation rate performance.” It adds new measures of first-generation rates and first-generation “graduation rate performance.”

What’s the point? U.S. News and World Report just states, “We increased the emphasis on how often schools' students from all socioeconomic backgrounds earned degrees and took advantage of information on graduate outcomes that was not available until recently.” Reading between the lines, though, the goal is to obfuscate the trade-off between merit and philanthropy by redefining philanthropy as merit!

Will U.S. News and World Report get away with it? Well, they’ve been corrupting their measures for a long time without facing much reputational damage. Parents and students still take official rankings pretty seriously. Vanderbilt President Daniel Diermeier pushed back against his school’s fall in the rankings, but outside observers probably chalked it up to sour grapes. (Meanwhile, my own GMU jumped up because we’re so “inclusive”; back in the old days, we used to just call that “low standards”).

Still, I think U.S. News and World Report has gone too far. If they keep corrupting the rankings until GMU is officially better than Vanderbilt, they won’t persuade parents, students, or employers that GMU is better than Vanderbilt. Instead, they will persuade parents, students, and employers that U.S. News and World Report rankings are fraudulent.

Critics have long mocked higher ed’s Kafkaesque rhetoric. How can the world’s most elite institutions pledge their undying commitment to egalitarianism with a straight face? Once standardized testing became standard, the standard solution to this tension was hypocrisy and tokenism. Be meritocratic, talk egalitarian, and admit a few subpar students. Your degree still sends a strong signal, and admins can still look in the mirror without too much guilt.

Over the last few decades, however, the standard solution unraveled. Proud commitment to preserving the prestige of their graduates’ degrees turned sour. Top schools are still in the signaling business, but it’s become a self-hating signaling: They certify intelligence and achievement while sneering at intelligence and achievement. Their dream, strangely, is to make egalitarianism the ultimate elitism. To end the trade-off between merit and philanthropy once and for all.

What’s wrong with this dream? Effective Altruism 101. If you’re in the business of certifying talent, lowering your standards is a terrible use of charitable resources. The best plan, rather, is the institutional version of “earning to give.” Feeling charitable? Run your school with utmost efficiency. Admit the best of the best. Charge them an arm and a leg for the privilege. Let the talented poor borrow against their future riches. Then take some of your surplus funds and carefully target them. Help war orphans. Fund deworming and malaria nets. Subsidize vaccines.

No top school does this, of course. Indeed, no top school has ever done this. Why not? Because like most human beings, admins would rather look good to their peers than actually do good for humanity. Most industries don’t even pretend to be charitable, but at least they do their job. Farmers don’t talk about “social justice”; they just grow food for us. College admins, in contrast, incoherently try to combine two jobs — signaling and philanthropy — and end up doing both poorly. They started with childish self-hatred… and ended up with compelling reasons to avoid looking at their own reflections.

I think it's worth considering the possibility that the universities are actually optimizing for what the people hiring their graduates want.

Firms that hire from the most elite schools face substantial PR (including from current and potential employees) pressure to have a more diverse workforce but also are legally and PR blocked from just lowering the bar for minority applicants. The universities are doing exactly what optimizes graduate desierability in such a world because the employer wants the best performers from both minority and non-minority groups but would prefer not to set a lower bar for test scores for minority hires for PR reasons. The universities just do the dirty work of washing away any overt signals of that difference.

And look, it makes sense since many jobs aren't that sensative to raw ability only the perception that you are hireing the best people. Truth is that lawyers at a white shoe firm don't need to be the very top level in ability but the clients need to believe they are choosing the most elite lawyers.

So it's not really a cost if some of your employees don't actually have the best test scores as long as that fact is effectively hidden and no one else can signal they do better (which would be hard given they have to say they avoid hiring those worse performing minorities like that other firm)

My primary issue with these changes isn't that I think they will cause a drop in standards (most admits don't get DEI bonuses) but that the schools have given up the one tool which lets them distinguish concienciousness and brilliance.

HS grades mostly measure conscientiousness above some low threshold of intelligence. And conscientiousness is important but the SAT used to provide a way for the brilliant but less conscientious kid to get into a great school. Since the SAT also is partially reflective of conscientiousness if you do really well despite only ok HS grades it probably suggests a fair bit of smarts.

This may not matter for corporations looking for generic hires but I fear it may reduce the number of truly brilliant scientists and innovators we produce. After all, its the brilliant but less conscientious kid who benefits most from a school where everyone else is taking hard classes because they (unlike their conscientious peers) would be most likely to not challenge themselves at state school.