I recently got this email from former student and current reader Matthew Gagnon. Reprinted with his permission.

P.S. I’ll reply next week. If you want to email Matthew directly, he’s matthew.o.gagnon@gmail.com.

Professor Caplan —

I hope things are well with you. You may recall, but I recently went through George Mason’s Master’s program in Economics online, and graduated this past spring. I wasn’t fortunate enough to have taken any of your classes via that program, but you and I met on a trip you took to Maine a couple years ago, and I’ve interviewed you a couple times for my morning radio show, which is based in Portland, Maine. I also run the Maine Policy Institute, which is a free-market think tank headquartered in Southern Maine.

The reason for my note to you is that I recently had cause to revisit your 1997 essay, "Why I Am Not an Austrian Economist," and it prompted me to want to ask what your own thoughts of self-definition are today, almost thirty years later. I find it an interesting question, just knowing what my own experiences have been related to the development of my own philosophy over the years.

I came to economics as a formal discipline a bit late. My undergraduate training was in political science, and my early career after college was in campaigns and elections, primarily in Washington. I didn’t academically study economics until I enrolled in the Mason’s distance program when I was already 41.

Flashing back twenty years ago, I was a fairly typical self-described libertarian, and as such I used to describe myself as broadly “Austrian” in philosophy. My attraction to Austrian economics had little to do with actually understanding it, but instead related to my perception of what Austrians represented in the broad debates about economic policy.

In my mind, they were the rebellious champions of free markets and individual liberty doing battle against the mindless orthodoxy of Keynesian interventionist thought in economics and government. They were the challengers of conventional wisdom, and didn’t play nice in the sandbox with others. A perfect fit for my youthful non-conformism.

In actuality, though, my grasp of economic theory was quite superficial. I had only the most rudimentary understanding of the Austrian tradition, and would have struggled to even define it if asked. I had no real sense of the depth of their theories or methodologies. I couldn't have told you much about Ludwig von Mises, Murray Rothbard or Friedrich Hayek, other than they were venerated as economic saints in comparison to the villainous Keynes. That damned rap battle didn’t help.

It wasn't until I grew a bit older that I started to become more engaged with the nuance and complexity within different schools of economic thought. I had certainly heard of Milton Friedman, but I had just assumed that as a cherished libertarian hero, he was more-or-less in the same camp as the Austrians on most things. Remember, at this point I had no real training as an economist and was just an interested politically-minded person. I had never really heard of the Chicago School, but when I started reading about it I began to figure out that while Friedman was a leading advocate for free markets, he wasn't an Austrian. In fact, it looked like some Austrians really hated the guy.

This prompted me to delve deeper into the distinctions between the Austrian and Chicago Schools, which ultimately resulted in me going much further than that, allowing me to begin to comprehend just how varied the field of economics was, and how little I understood about it all.

Then in 2010 a funny thing happened. Back in my home state of Maine, the state Republican Party Convention was overtaken by libertarian activists, who then proceeded to introduce a new platform. One of the planks included a call to, "return to the principles of Austrian Economics, and redirect the economy back to one of incentives to save and invest." This development intrigued me. Why the specific emphasis on Austrian Economics? Was it, like my youthful self-identification, a result of sentiment, rather than actual knowledge? Would the people who wrote that plank struggles as much as I would to even definite it?

That was my turning point. After that, I simply had to learn more and settle the question for myself. That's when I actually started reading Hayek, Mises, Rothbard, as well as Friedman and others. I wanted to understand not just their economic theories but also the philosophical underpinnings and methodological approaches that set them apart from one another. I learned an awful lot about the internal debates within libertarianism — the divides between Rothbard and Hayek, between Hayek and Friedman, and between various organizations such as the Mises Institute and Cato. I even got into the differences between Ayn Rand's objectivism — or what I would call the gateway drug of libertarianism — and the broader libertarian movement.

This was pretty humbling. To realize that there was that much internal discord among figures that I had believed to be generally aligned with one another ultimately deepened my own confusion about what I was. I’m not sure anyone has ever had an existential crisis over what their economic philosophy could be defined as, but I may have come close.

In the end, this was one of the primary motivations for pursuing a Master’s in Economics, and in my choice of George Mason as the place I would study it. I wanted to gain a deeper understanding of both mainstream economics, as well as the Austrian philosophy. I wanted to explore some of these questions in depth, and lift the veil of ignorance from my eyes to help me better understand what I believed and why.

After going through the program, which was excellent by the way, I now think I can say definitively, as you once did, that I am not an Austrian economist. I remain sympathetic to many Austrian insights, but I place far too much value in empirical analysis, data, and mathematical and statistical modeling — tools often rejected by the Austrian School — to really count myself among them. I suppose in the long run, I side more with the Friedmans than the Rothbards, though I do feel a strong pull to the Hayekian wing of Austrianism, particularly the emphasis on things like spontaneous order and the knowledge problem.

In any event, that brings me to the question I have for you:

Nearly three decades have passed since you wrote your essay distancing yourself from the Austrian School. Given the passage of time and your experiences teaching and collaborating with colleagues who are prominent figures in Austrian Economics, I'm curious whether or not you still hold the same position today? Has your perspective evolved in light of new developments in the field or through interactions with your colleagues? Have you found areas of convergence that weren't apparent before, or have you perhaps become more convinced of your original stance?

As my own story illustrates, we all reassess our beliefs as we gain new experiences and insights. I'm very interested to hear how, if at all, your views on the Austrian School have changed.

If you've already addressed this topic elsewhere, I apologize for any redundancy. However, I believe that an updated reflection from you would offer valuable insights to those of us grappling with similar questions about our own intellectual identities within economics, particularly for those who may be outside the economics profession, but be interested amateurs.

Thank you for taking the time to read my note, and I look forward to any thoughts you might be willing to share.

Sincerely,

Matthew Gagnon

Great letter. Look forward to your response.

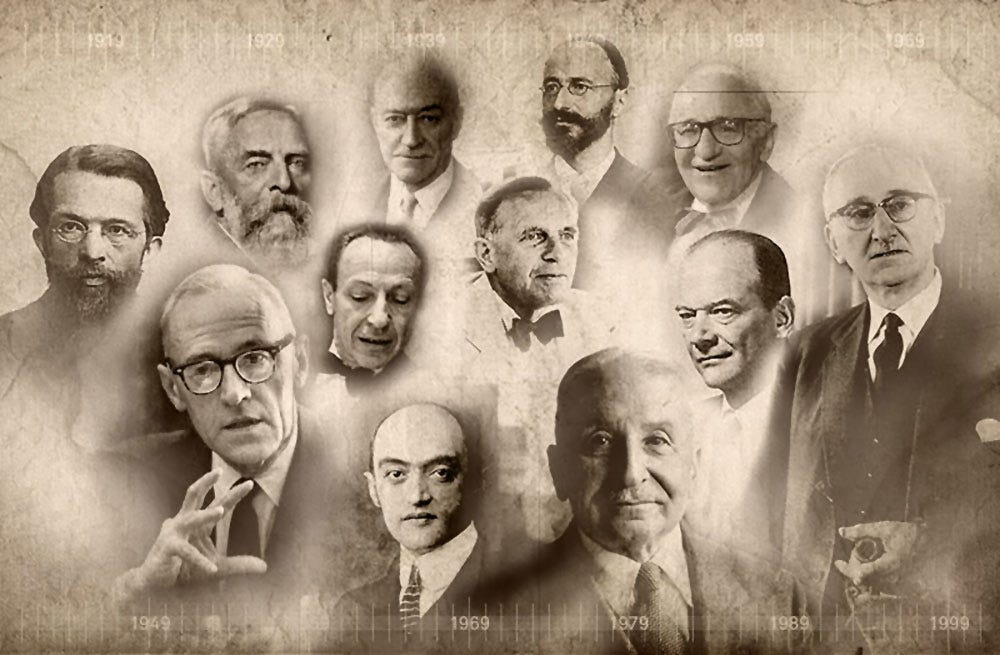

Haven’t read this piece yet, but love the photo!