Recently, I got a new book idea. After soliciting possible titles, I really liked Nathan Goodman’s Unbeatable, to which I added the subtitle The Brutally Honest Case for Free Markets. Before long, I was so jazzed about the idea - and the sales potential - that I decided to rearrange my queue to try writing Unbeatable first, and finish my Poverty: Who To Blame later.

Writing my books has always taken years, because I’m always thinking, “At minimum, I personally have to be convinced that I’m writing the very best book ever written on my topic.” A fine prescription for writer’s block, though in the long-run this self-flagellating megalomania does wonders for quality. For Unbeatable, however, I’ve been writing fairly rapidly, yet remain very pleased with the quality. To whet your appetite, here are the first couples of pages of the Introduction. Hopefully, you’ll enjoy them.

Introduction: When Good Sounds Bad and Bad Sounds Good

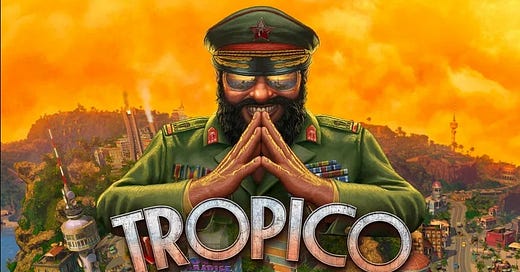

When my twin sons were about ten, they loved a videogame called Tropico. The game makes you the caudillo of a Caribbean island – its sovereign ruler and economic czar. As you play, you face constant criticism from the island’s political factions. If you displease too many of your subjects, you fall from power and lose the game. Game after game, the most vocal critics of my twins’ regimes were the Communists. Which led to a memorable conversation.

“Dad, I’m really confused about the Communists in Tropico.”

“How so?”

“Well, you’re always telling us how terrible the Communists are.”

Guilty as charged. My wife and her parents were refugees from Communist Romania. Reading books about mass murder and slave labor under the likes of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao is one of my long-time hobbies. I’ve written several academic pieces about the economics and politics of Communism, including an encyclopedia article. And it is in my character to share my knowledge with the next generation.

True to form, I responded, “Yes, ‘terrible’ is right.”

“In the game, though, the requests of the Communists always sound so good: grow more food for the hungry; build better housing for the poor; give everyone free health care. What’s wrong with all that?”

Hearing this thoughtful question put a big smile on my face. I was so proud of my progeny. And an answer was already in my head. “Sons,” I began, “in life, there are many things that sound good but are bad – and many things that sound bad but are good. Suppose someone says, ‘The government should just give everybody whatever they need.’ How does that sound?”

“Good!”

“Sure does. But if government just gives everyone whatever they need, what incentive is there to actually produce the goods the government wants to hand out?”

The twins furrowed their brows for a moment. “Not much incentive at all.”

“Right, especially if you define ‘needs’ broadly. And that’s a big part of the reason why practically everyone in Communist countries – except for the Party elite – lived in what we’d consider dire poverty.”

“Huh.”

“In contrast, suppose someone says, ‘Individuals should just work hard to take care of their own needs.’ How does that sound?”

“Bad.”

“Correct. Yet the result is that people produce lots of stuff. And that’s a big part of the reason why practically everyone in the world’s most capitalist countries is, by world and historic standards, amazingly rich.”

Over the years, my sons didn’t just repeatedly remind me of this conversation. They repeatedly showed me that they absorbed the central point. A casual listener might think that I was just informing them that Communism was bad and capitalism was good. What my sons took away, to my elation, was the deeper lesson that what sounds good is often bad – and what sounds bad is often good. Which spurred much precocious critical thinking. Whenever they heard teachers or school officials or priests or parents or politicians or other kids speak sugarcoated words, my sons were listening skeptically, ever-ready to ask the One Great Question: “That sounds good, but is it really true?”

If your intent is to persuade any among the unpersuaded and you immediately dismiss communism with reference to incentives and pleas to your own authority, you will fail. Those who think communism sounds good (and are not your own children) will not consider “communism is bad because no one has any incentives to produce” to be a knockdown argument. They have heard that before and considered that before.

If instead you intend to write only for the already persuaded, kudos, quality start.

Communism is deeply rooted in our culture. Took Christianity: richs are banned from heaven (at least if we don't find a way of passing camels trough the eye of a needle).

An envy is a very powerful force in humans. Communism promise of leveling us with all the "have more than us" is truly unbeatable. Sweet revenge!

And championing comunism ideals make us feel good about ourselves at a very low individual price. Communism includes making others pay for our virtue signalling. Unbeatable too.

Communism idea is so powerful that it is embeded in a lot of "democratic" constitutions.

Abandoning communism (not a bad titlte, by the way) requires much more than good reasoning and good lessons on economic history. It is something we need to feel, not to think. We are all communist at heart

Good luck!