The Unabridged Ridley-Caplan Exchange

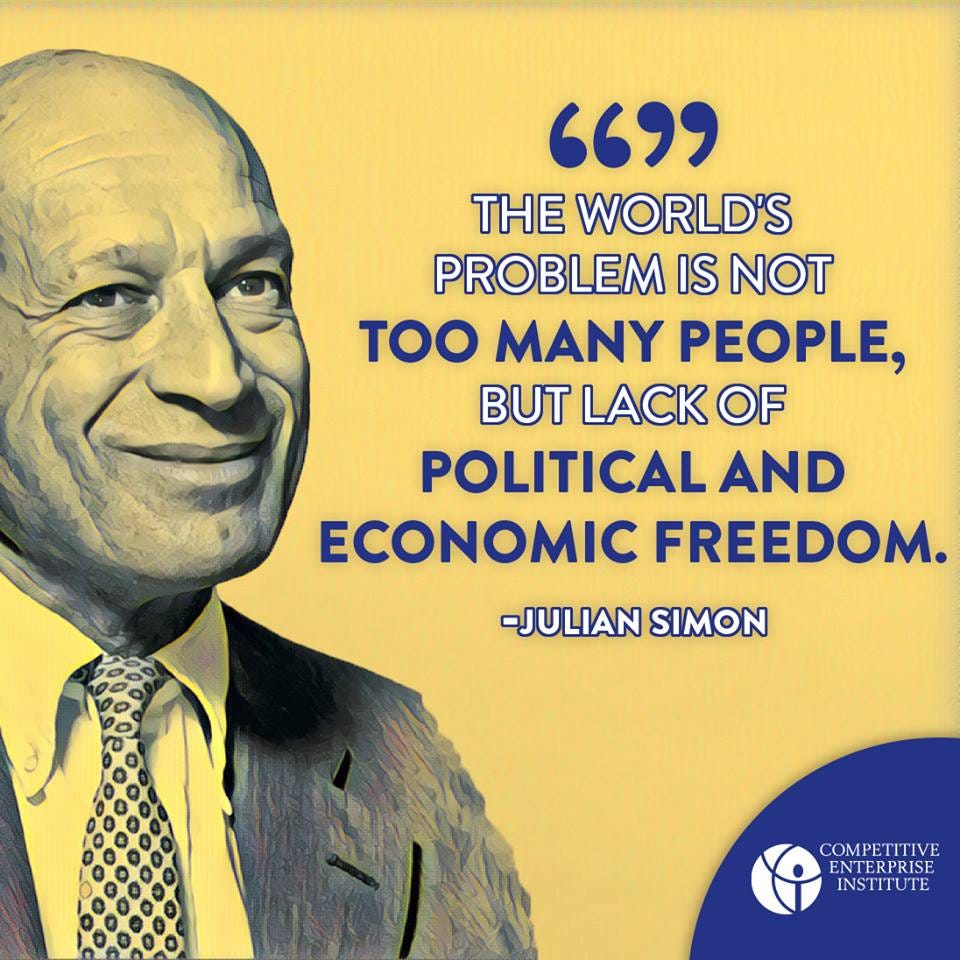

Rounds 3-6 of our 2012 argument about Julian Simon, population and innovation.

Back in 2012, the great Matt Ridley criticized the great Julian Simon. I then criticized Ridley’s criticism. After I reposted my original critique last weekend, I remembered that the Ridley-Caplan exchange actually went on for four additional rounds.

Here’s the full exchange, in sequence, counting Ridley’s original statement as Round #1, and my original response as Round #2.

Round #3: Ridley responds.

Thanks for the comments, Bryan. Let me make three quick responses.

First, I know of a lot of people who are not conventionally clever but who contribute to innovation by making tiny tweaks to machines or routines. That’s very much my point, that innovation is not a series of intuitive leaps but often unplanned micro-steps that come together. (Kevin Kelly’s book What Technology Wants is a brilliant addition to this literature.) I am thinking of one guy in particular who can adjust or mend almost anything, but could never pass an exam or hold much of a conversation. I just think there is a strong prejudice among academic types (of which I am one) to miss the point that most innovation consists of bottom-up infinitesimal cumulative improvements and to think in terms of big ideas: the inspiration, rather than the perspiration.

As for small countries leading the world, I would argue it is almost the rule. To Athens, Genoa, Holland, let me add New York (for much of America was superfluous to America’s economic explosion in the nineteenth century), San Jose, CA (for there was a remarkable concentration of innovation there in recent decades) Singapore, Hongkong, or going back in time Tyre, Sybaris, Pataliputra. Britain, when it embarked on the industrial revolution had less than half the population of France: this was clearly no disadvantage. I think it is rather striking how infrequently big countries like Russia, France, the Roman empire, the Ming Empire do lead the world economically. (Military might is a different matter.)

As for the notion that both population and connectedness matter, sure up to a point. To have 10,000 people is a lot better than to have 5,000. But to have a billion instead of 500m? I’m not convinced.

Best wishes

Matt Ridley

Round #4: I reply to Ridley.

Matt Ridley graciously replies to my critique of his Julian Simon Award Lecture in the comments. Ridley’s in blockquotes, I’m not:

First, I know of a lot of people who are not conventionally clever but who contribute to innovation by making tiny tweaks to machines or routines. That’s very much my point, that innovation is not a series of intuitive leaps but often unplanned micro-steps that come together. (Kevin Kelly’s book What Technology Wants is a brilliant addition to this literature.) I am thinking of one guy in particular who can adjust or mend almost anything, but could never pass an exam or hold much of a conversation. I just think there is a strong prejudice among academic types (of which I am one) to miss the point that most innovation consists of bottom-up infinitesimal cumulative improvements and to think in terms of big ideas: the inspiration, rather than the perspiration.

“Tiny tweaks” are great, but the idea that a significant fraction of tweaks come from people who “could never pass an exam or hold much of a conversation” is quite implausible. Even most smart people are stuck in a rut. And the less smart you are, the more likely your “tweak” is to actually make things worse.

As for small countries leading the world, I would argue it is almost the rule. To Athens, Genoa, Holland, let me add New York (for much of America was superfluous to America’s economic explosion in the nineteenth century), San Jose, CA (for there was a remarkable concentration of innovation there in recent decades) Singapore, Hongkong, or going back in time Tyre, Sybaris, Pataliputra.

So the United States – the third most populous nation on earth – doesn’t count against your view because the actual innovations tend to be concentrated in particular cities like New York and San Jose? I say you have to step back and realize that the probability that an innovative city arises in a country depends on the country’s (and, with immigration, the world’s) total population.

Britain, when it embarked on the industrial revolution had less than half the population of France: this was clearly no disadvantage. I think it is rather striking how infrequently big countries like Russia, France, the Roman empire, the Ming Empire do lead the world economically.

Britain wasn’t the most populous county in the world at the time, but it was one of them. According to Angus Maddison’s data, the only countries with higher population than Great Britain in 1850 were China, India, Russia, France, and Japan (and the countries that later became Germany, if you want to conceptually consolidate them). I’m not saying that the population:innovation link is perfect, but it’s fairly positive – as you can see when you check the correlation between population and almost any observable measure of innovation. Challenge for Ridley: I know you don’t like Nobel prize or patent numbers; is there any measure of innovation that you do accept that doesn’t positively correlate with population?

Your counter-examples are definitely thought-provoking, but I still say you’re missing the big historical picture: Most innovation has come from regions of the world with large, connected populations (especially Eurasia), and higher-population periods of human history are much more innovative than lower-population periods.

As for the notion that both population and connectedness matter, sure up to a point. To have 10,000 people is a lot better than to have 5,000. But to have a billion instead of 500m? I’m not convinced.

Suppose we randomly deleted half the countries on earth. Would you seriously not expect innovation to sharply decline?

Round #5: Ridley’s rejoinder.

But your challenge mistakes my argument. I have not argued that there is no positive correlation of innovation with population, only that, as population size increases, population size alone will become a diminishing influence compared with population interconnectedness. You are trying to push me into a rhetorical box I don’t wish to occupy: that at some level population growth stops helping innovation or starts harming it. That may be a case somebody wants to make — but it’s not the case I’ve argued.

Instead I have argued that bigger populations will always be more innovative, of course. But once populations are large the most effective way to make them more innovative is not so much to make them larger as to make them more interconnected. It’s a matter of enabling people’s ideas to mix more. So you can have large populations, as in Ming China, that stagnate innovation-wise, because people are prevented from mixing, meeting, urbanising, communicating, travelling etc. Whereas America owes its lead in innovation in the 20th century — as Britain did in the nineteenth — more to its freedom of exchange than to its population size.

So I am combatting the idea that it’s a matter of demographic statistics, that there’s a better chance you’ll get more geniuses because you have more people. Simon several times came close to implying this and it’s a common argument put forward by various people today and I think it misses the point: that ordinary people able to exchange ideas produce a great deal of innovation. The more people the better, and the more exchange the better.

A genetic analogy might help. Bigger genomes get more mutations. But genomes that exchange genes more often — ie, have shorter generation times — innovate more, because they throw up more combinations of sequences. As you know, I think there is a pretty good analogy between the way sex accelerates evolution and the way exchange accelerates innovation.

Thanks for the exchange!

Round #6: My final word.

Matt Ridley once again graciously responds in the comments. Our differences appear to have largely evaporated. Ridley’s in blockquotes, I’m not.

But your challenge mistakes my argument. I have not argued that there is no positive correlation of innovation with population, only that, as population size increases, population size alone will become a diminishing influence compared with population interconnectedness. You are trying to push me into a rhetorical box I don’t wish to occupy: that at some level population growth stops helping innovation or starts harming it. That may be a case somebody wants to make — but it’s not the case I’ve argued.

Several of your statements seem hard to interpret any other way, especially: “As for small countries leading the world, I would argue it is almost the rule,” and “To have 10,000 people is a lot better than to have 5,000. But to have a billion instead of 500m? I’m not convinced.” Still, if you agree that population is good for innovation, I’m satisfied.

Instead I have argued that bigger populations will always be more innovative, of course. But once populations are large the most effective way to make them more innovative is not so much to make them larger as to make them more interconnected.

Sure, as a matter of policy, it’s far easier to remove barriers to communication and trade than to increase the number of humans on earth. But that doesn’t mean that interconnection is “more important” than population, just more policy-sensitive.

A genetic analogy might help. Bigger genomes get more mutations. But genomes that exchange genes more often — i.e., have shorter generation times — innovate more, because they throw up more combinations of sequences.

A fine analogy, I’m happy to accept it. 🙂

Interesting debate/conversation. I worked the last 26 years of my career at Los Alamos Labs, which is a concentration of science and engineering PhDs, and out of which significant innovation has come, despite extensive rules and regulations which also serve to stifle innovation. I would suggest that most innovation comes when the following conditions exist:

- Innovative and creative people gather in a common community.

- The culture of the community is open to innovation. This has not been common historically.

- Travel to that community is feasible, such that people who feel stifled in their home town are able to move to join the innovative community.

I don't see any argument against the position that a larger population will tend to have more creative and innovative people, but if the above conditions do not exist, they will make little if any progress.

I will also note that people who seek employment in government almost exclusively fall outside of the innovative and creative group, but they also tend to have control issues. They will go to great lengths to prevent change or innovation that might upset their position or power. Thus, the more "mature" a government becomes, the less innovative its population will be, regardless of size.

Based on these conditions, I would expect to see far more innovation out of India in the coming decades than out of China, despite similar populations. And assuming no major changes in the governments of either.

Nice dialog. I would challenge Matt a bit on the "mutations are innovations" idea. Mutations are accidents, innovations are intentional. Genes don't have ideas or intuitions. It is knowledge that human beings are trying to discover and create. The process is economic, not biologic. Great respect for both of you for demonstrating how to dialog.