Robert Putnam, famed author of Bowling Alone, has spent much of his career regretfully publicizing the dangers of diversity. His most famous claim, of course, is that “social capital” – usually operationalized as “trust” – is vital for a good society. And though he’s a liberal in good standing, he urges us to face facts: diversity – especially ethnic diversity – is very bad for trust. As Putnam’s 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture summarizes:

Diversity does not produce ‘bad race relations’ or ethnically-defined group hostility, our findings suggest. Rather, inhabitants of diverse communities tend to withdraw from collective life, to distrust their neighbours, regardless of the colour of their skin, to withdraw even from close friends, to expect the worst from their community and its leaders, to volunteer less, give less to charity and work on community projects less often, to register to vote less, to agitate for social reform more , but have less faith that they can actually make a difference, and to huddle unhappily in front of the television. Note that this pattern encompasses attitudes and behavior, bridging and bonding social capital, public and private connections. Diversity, at least in the short run, seems to bring out the turtle in all of us.

What’s impressive about Putnam’s piece, however, is that he takes the danger of spurious correlation so seriously:

[T]he diverse communities in our study are clearly distinctive in many other ways apart from their ethnic composition. Diverse communities tend to be larger, more mobile, less egalitarian, more crime-ridden and so on. Moreover, individuals who live in ethnically diverse places are different in many ways from people who live in homogeneous areas. They tend to be poorer, less educated, less likely to own their home, less likely to speak English and so on. In order to exclude the possibility that the seeming ‘effect’ of diversity is spurious, we must control, statistically speaking, for many other factors.

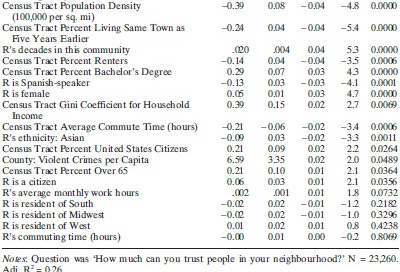

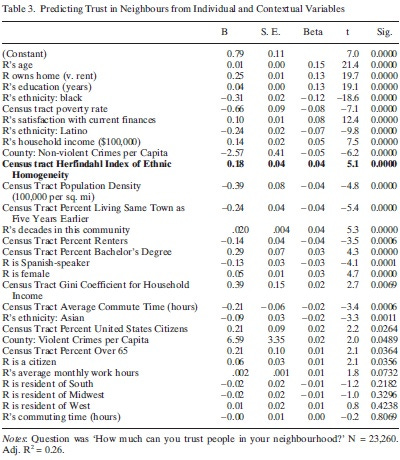

Indeed. And here is what Putnam finds when he uses multiple regression to predict individuals’ trust on a 4-point scale.

Putnam’s measure of diversity – the Census tract Herfindahl Index of Ethnic Homogeneity – is in bold. It’s the sum of the squares of each group’s population shares, so it theoretically ranges – note the reverse coding! – from 0 (infinite diversity) to 1 (zero diversity). But since Putnam only sub-divides the population into four groups – Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Asian – his diversity measure can’t fall below 4*.25^2=.25.

Now imagine we move from a world with zero diversity to the maximum diversity. According to Putnam’s results, how much will this reduce trust? .18*.75=.14. Is that a lot? No way. Remember, he’s using a 4-point scale. And since the current national Herfindahl Index of Ethnic Homogeneity is about .46, moving from the diversity of today to maximum diversity reduces predicted trust by a microscopic .18*.21=.04. “Diverse” communities have low trust, but the reason isn’t that diversity hurts trust; it’s that non-whites – especially blacks and Hispanics – have low trust.

What’s especially striking, though, is that Putnam finds several variables that strongly predict trust that almost no one discusses. Look at the effect of home-ownership. Not only do home-owners average .25 higher trust; there’s also a -.14 coefficient on “Census Tract Percent Renters.” Net effect of moving from 0% to 100% home ownership: .39. Holding all else constant, citizenship is good for trust: a mere .06 for the individual, but a solid .21 for the community. Net effect of moving from 0% to 100% citizenship: .27. There are also big effects of crime, population density, and commuting time. Geographic mobility, strangely, seems to reduce individual trust but raise social trust.

The latter variables don’t just matter more than trust; they’re also much more policy-relevant. Reducing diversity is very hard; indeed, without massive human rights violations, it’s almost impossible. Home ownership, in contrast, can be fostered with not only tax incentives (the standard way), but housing deregulation (the wise way). Population density, similarly, can be reduced by deregulating development of surburban and rural land. Commuting time can be slashed with better public transit (the standard way) or congestion pricing (the wise way). Better policing and law enforcement – not to mention thoughtful decriminalization – all reduce crime rates. And if we take the estimated benefits of citizenship at face value, it can be raised to 100% with the stroke of an amnesty pen.

Putnam’s numerous alt-right fans seem to relish his anti-diversity claims because he lends an air of respectability to their misanthropy. But if you read Putnam’s whole article, it’s hard to detect any ill will. Why then would he so grossly overstate the dangers of diversity? My best story is just confirmation bias. Early on in his research, Putnam found strong univariate links between diversity and trust. When better methods show that this relationship matters slightly, Putnam – like most human beings – treats this as a vindication of his initial claims. But if all you knew were Putnam’s final results from Table 3, you’d never reach Putnam’s anti-diversity conclusion. Diversity’s so unimportant for trust, you might not mention it at all.

The post appeared first on Econlib.

I find it hard to square your conclusions with what is actually happening on the ground all over Europe. That is, the rise of populist political parties that are strongly anti-immigration (primarily with respect to Muslims), including proposals not only to essentially end it but to deport (a la Trump) migrants already residing in the host country. These parties are usually the second or third most popular party in these states, with fractured polities, and are even part of the governing coalition. Many of the "mainstream" parties are now adopting serious restrictions on migration to co-opt support from the populists. I dunno, call me crazy, but it seems that there is little social trust between say ethnic Germans, French, Swedes, etc. and their Muslim neighbors.

Your second to last paragraph is making some assumptions about how the relationships work that I do not think are at all reasonable, being much more likely to be driven by third things than the 1:1 relationships.

Home Ownership: Is it the fact that people own instead of rent, or the fact that people who own tend to live in the same place longer (so you know each other) and the fact that the sorts of people who save up enough to buy a house and maintain it tend to be more trustworthy people? In other words, do you think that if we just gave houses to everyone the average level of trustworthiness would go up?

Population Density: Probably helps, although probably as a function of how many bad actors there will be in an area. The power laws in play in crime and other bad behavior make the absolute number of bad people in an area more relevant than the percentage.

Commuting Time: This seems to be a proxy for density, but possibly is also due to the "lots of people I don't know around all the time." Not confident at all, but I would guess trust goes up when people see a smaller number of people and can track their behaviors better.

Better Policing: I think you are spot on here, with the addition of "actually prosecuting crimes". This reduces the absolute number of criminals, and thus the relevant number of crimes. One point about decriminalizing, however, is that decriminalizing murder won't make people feel more trusting. It is less that things are illegal in the legislative sense that matters and more about whether the actual norms are being followed. The link between crime rate and trust is broken here; you could declare being Amish illegal tomorrow, and despite the crime rate skyrocketing their intragroup social trust measure wouldn't go down.

Citizenship: This seems a strange assertion. It doesn't seem likely to me that there mere fact of citizenship is what is driving low trust here. People don't learn citizenship status and then derive how much they trust someone based on that, but rather impute citizenship status based on other signals. As such, lower rates of citizenship correlate with lower rates of trust almost certainly because the behaviors of non-citizens are such that trust goes down (likely among both citizens AND non-citizens!) That might be to differences in norms and expectations, or outright bad behavior, whatever, but it is nearly infeasible that what is causing the distrust is knowledge of someone's citizenship status, such that changing that status with a swipe of the pen would affect trust.

(You might be able to test that, in fact, by looking at trust based on various levels of "you are allowed to be here", comparing ratios of visas, green cards, naturalized citizens, and how those societies trust each other. Getting data would be hard, I suspect.)

In all, that second to last paragraph seems to be demanding a cry of "Correlation does not equal causation!" Possibly also a reminder that trying to put pressure on one side of a statistical regularity is unlikely to be effective at changing the other side.