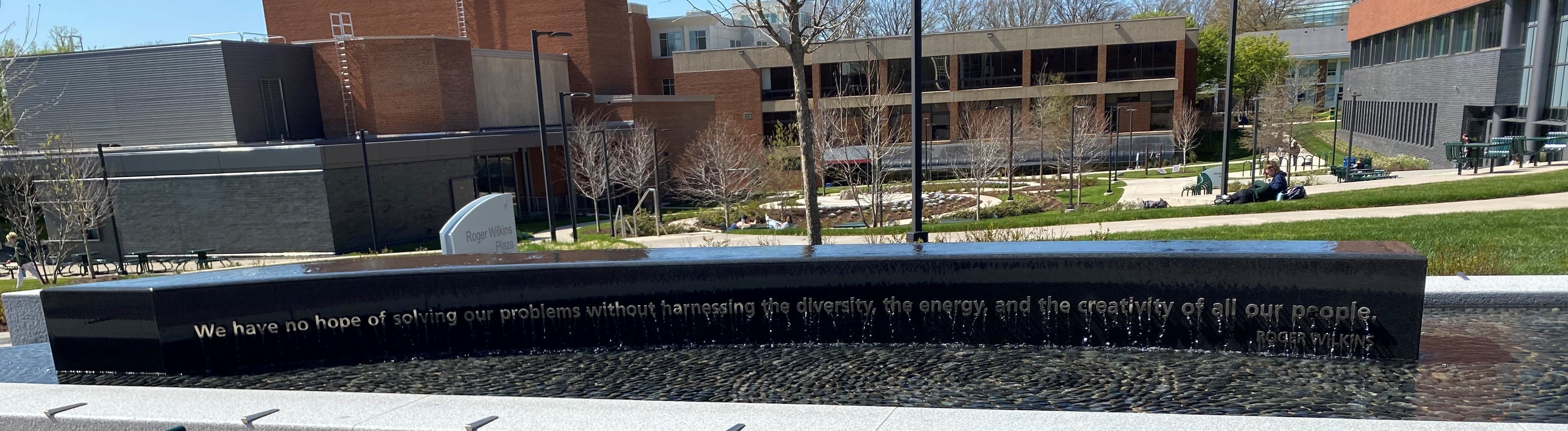

At the heart of George Mason’s campus lies a fountain with a big inscription. The quote, by Roger Wilkins, reads:

We have no hope of solving our problems without harnessing the diversity, the energy, and the creativity of all our people.

Who could object to such a mild-mannered, well-meaning statement? I do, because it’s obviously untrue, a mess of hyperbole and Social Desirability Bias.

Let me explain in detail.

No society in the entire history of the world has ever “harnessed the diversity, the energy, and the creativity” of all of its people. Not even close.

Yet every society, no matter how dysfunctional, has solved some of its problems.

To say “we have no hope” of doing something that every society has achieved is absurd.

What if you interpret “solving our problems” as “solving all of our problems”? Then we have no hope of success regardless of what we harness, because the goal is just too hard.

Plenty of “our people” plainly aren’t going to help us solve any problems. Most people simply aren’t creative - never have been, never will be. Many people, similarly, have bad attitudes. They’re not going to help solve problems, either. A few people even have crippling health problems that preclude them from contributing despite their fervent wish to help. How are people in comas supposed to help us solve anything?

You could object, “This is all obvious. Everyone instantly sees that Wilkins’ quote is literally false.” But practically the opposite is true. Most people who take the time to read the quote think, “So true, if only everyone would just admit Wilkins’ humble truth, we’d live in a wonderful world.” Saying that “Everyone knows that this quote is false” is like saying, “Everyone knows that creationism is false.” When a belief makes people feel important, humans often embrace it uncritically - and get angry at those of us who doubt.

Alternately, you could say, “Sure, lots of people mistake Wilkins’ quote for a literal truth. The point, though, is to encourage us to encourage each other to work for our common betterment.” Or to be blunt, “It’s a Noble Lie.” But this, too, raises big questions.

To start, what is the evidence that Noble Lies in general are, on average, a net positive? No human society has ever fully embraced literal truth. But history’s most functional societies seem to prize literal truth relatively highly. And history’s most dysfunctional societies - totalitarian regimes and theocracies - angrily criminalize literal truth.

Second, what is the evidence that this specific Noble Lie is a net positive? Why is it better to believe that “all our people” are critical rather than “the best and brightest”? You can be open-minded about the identity and background of the best and brightest while still heaping glory upon whoever they turn out to be.

I’m well-aware that asking such questions provokes accusations of autism on my part. But as I’ve said before, such accusations are unfair to non-autistics. Neurotypicals are fully capable of setting aside sugar-coated slogans and seeing the world clearly.

And we have no hope of solving our problems unless they do!

I’m trying to understand why people want to believe that the quote is true. One thought is that it is emotional and there are good reasons for emotions. For example, it makes no sense for any individual to agree to fight in a war against another country but it might be desirable for the society as a whole. In some ways emotion could be a way to harness collective efforts that might allow a group to outcompete but be illogical for the individual. The cost is fountains.

The "no hope" and "all" parts are hyperbole, shorn of flourishes it's stating a theory that society would benefit from developing human capital all through the bell curve. Implying, as you noticed, that heretofore resources were inefficiently concentrated in developing the best and the brightest.

Now that theory may not be *correct*, but isn't it obvious that GMU's existence is an application of that theory, given the institutional history? That's why it's on the fountain.