“Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!” Accusing your opponents of hypocrisy is one of the most effective rhetorical tactics known to man. But does the fact that your opponents are hypocrites provide substantive evidence against the correctness of their views? Or is the highlighting of hypocrisy merely another sleazy variant of the ad hominem fallacy?

The cop-out answer is: It depends. But I refuse to cop out. I submit for your approval the following typology of hypocrisy to light our way.

There are two distinct kinds of hypocrisy: normative hypocrisy and positive hypocrisy.

Normative hypocrisy is when your moral views clash with your behavior. A good example of normative hypocrisy: A person says “Everyone is morally obligated to be a vegan,” even though they eat meat.

Positive hypocrisy is when your descriptive views clash with your behavior. A good example of positive hypocrisy: A person says, “Vegan food is invariably tastier, cheaper, and healthier,” even though they eat meat.

The default explanation for normative hypocrisy is that the speaker is morally flawed. Which shows something about the speaker’s integrity, but not much about the correctness of his normative claims.

The default explanation for positive hypocrisy, in contrast, is… what exactly? Confronted with, “If vegan food is really tastier, cheaper, and healthier, why are you eating meat?!” how can you even respond? “I dislike tastiness”? “I love wasting money”? “I want to be sick”? While these are all logically valid answers, they’re too stilted to take seriously. The default explanation for positive hypocrisy, rather, is that the speaker himself disbelieves his original statement.

In slogan form: It’s not merely that I don’t believe you. You don’t believe you!

The upshot: While normative hypocrisy shows little about your correctness, positive hypocrisy shows a lot about your correctness.

At this point, it’s tempting to insist that normative hypocrisy is vastly more common than positive hypocrisy. But if you’re paying attention, positive hypocrisy is ubiquitous. Some notable cases:

Saying “I live in a hellhole” when you could easily afford to move.

Saying, “I care more about culture than money” when you could easily get a lot more culture in exchange for a modest amount of money.

Saying, “Religion is the most important thing in my life” when you don’t go to church or otherwise spend time on your faith.

Saying, “My vote really counts” when you don’t vote.

Saying “I would never do anything to hurt my family” when you’re a severe alcoholic, chronic adulterer, etc.

Saying, “I can’t change the way I am” when you routinely alter your behavior in response to incentives.

Saying, “I would gladly die for this country” while avoiding military service.

Saying, “People literally go to hell for doing X” even though you do X.

Saying, “This is the best country in the world, I’d never leave” — then leaving.

“While normative hypocrisy shows little about your correctness, positive hypocrisy shows a lot about your correctness.” This lesson seems awfully solid. But is there any reason to think that I’ve underrated the epistemic relevance of normative hypocrisy? Overrated the epistemic relevance of positive hypocrisy?

Let’s start with normative hypocrisy. Since it plainly reveals a lack of integrity, the next question to ask is: “On average, does lack of integrity mean lower credibility?” And the answer is almost definitely yes. If you can independently verify the speaker’s statements, then credibility is not an issue. But on any issue where the trustworthiness of the speaker matters, so does lack of integrity.

On further reflection, however, we should acknowledge that this normative hypocrisy-reliability link, though real, is weak. Why? Because psychologically normal humans have (a) low absolute integrity, and (b) countless chances to be hypocritical. In Bayesian terms, what undermines your credibility is being more normatively hypocritical than the typical human. But no single instance of such hypocrisy is very revealing. Which is why you probably should only slightly downgrade your confidence in the macroeconomic research of, say, divorced Catholics.

Normative hypocrisy becomes more revealing, however, if you have independent knowledge that the speaker is extremely morally scrupulous. I’ve previously dubbed this “The Argument from Conscience.” If a person has a well-established track record of following onerous moral principles, their violation of one specific stated principles should make us doubt whether the person sincerely believes the violated principle. Granted, this inference is hardly bulletproof. Maybe it just shows that we’ve been giving the person an A+ for integrity when they only deserve an A. But in Bayesian terms, the Argument from Conscience is at least moderately probative when its assumptions hold.

What about positive hypocrisy? Under what conditions does “You eat meat” cease to be a powerful reason to doubt a person’s claim that “Vegan food is invariably tastier, cheaper, and healthier”?

First and foremost, if the speaker is extremely stupid. How stupid? Stupid enough to not know that chicken is meat, churches exist within driving distance, drunkenness hurts your family, and so on.

Secondarily, if the clash between your descriptive views and your behavior is hard to discover. (In case you haven’t heard, vegans, Soylent Green… is… people!)

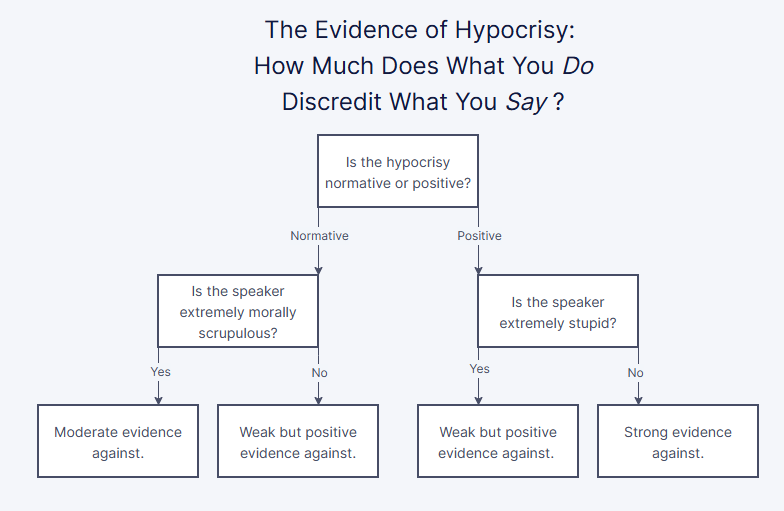

Returning to the original question, to what extent does the fact that your opponents are hypocrites provide substantive evidence about the correctness of their views? We can use my typology to construct this nifty flow chart.

While this is only a first pass, I’ll still pronounce it a major advance. Contrary to demagogic insinuations, hypocrisy is rarely decisive evidence that anyone’s views are false. But contrary to hypocrisy’s urbane apologists, hypocrisy is almost always at least slightly discrediting. In special circumstances, even normative hypocrisy is pretty discrediting. And except in special circumstances, positive hypocrisy is extremely discrediting. If your actions show that even you don’t believe you, why should anyone else?

The trouble with market research is that people don't think what they feel, they don't say what they think and they don't do what they say.”

― David Ogilvy

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/9476561-the-trouble-with-market-research-is-that-people-don-t-think

I don’t know of anyone who says that “vegan food is invariably tastier” or “cheaper” than meat, which would obviously not be true. I’ve been vegetarian for over 30 years, but of course I admit that some meat is cheap and tastes good, and I’ve never heard of a vegetarian/vegan saying otherwise. So that’s a weird example.